One of the major requirements of W courses is that instructors provide feedback on students’ writing. Responding to student writing is time-consuming and challenging; yet it is also one of the most useful ways to help students become better writers. Below are some best practices, drawn from the field of rhetoric and composition (and English studies largely), for responding to student writing.

Time Management and Organization

Managing your time when you are grading a lot of writing can be difficult, and sometimes just knowing how to begin tackling a set of papers can be a challenge. There really is no right or wrong way to manage your time when grading, but the following strategies and tips have been touted as useful by writing studies practitioners:

- Design a clear assignment. While this advice may seem obvious, it’s easy to create an assignment that is missing key components or that is not clear to students. Spend a good amount of time designing a clear, focused assignment so you avoid a lot of student questions or papers that don’t do what you expect them to. Consider workshopping a draft of the assignment sheet with your class or having a colleague look it over. The Chargers as Pedagogical Partners (CAPP) program can also help with this. CAPP pairs student consultants and instructors together as co-developers of course materials. Student consultants leverage their expertise as students to offer instructors feedback on course materials and more. Visit the CAPP website to learn more and request a partnership.

- Review the assignment and grading criteria. Briefly reviewing the assignment and grading criteria before you sit down to grade a stack of papers usually helps you avoid having to revisit the assignment sheet and rubric multiple times while grading.

- Skim multiple essays to get a sense of average class performance. Some disagree with this approach, but it can be useful to get a sense of how students, on average, seem to be performing on an assignment. Skimming the essays before commenting on them may help you find common errors, for which you can prepare “stock comments.”

- Set a timer. Some writing teachers find it useful to give themselves a time limit (think: 15 minutes for a 5-page paper) and set a timer to limit the amount of time they spend writing feedback.

- Pre-determine the depth of feedback. Prior to leaving comments, decide not only how much time you’ll spend leaving comments, but also how in-depth your comments will be. For example, if you are grading a final draft, you might decide to mark up one page for grammar and leave end comments with three major items that needed revision. Making these decisions ahead of time will keep you from getting in the weeds and spending too long on a paper that needs a lot of work.

- Give general feedback to the whole class. If you identify common errors during skimming or commenting, consider collecting them in a Word document. For example, if many students have sentence fragments in their writing, consider writing the word “fragment” on a student’s paper but then sharing a Word document with the whole class, which explains what a fragment is and offers an example.

- You can also talk to students beforehand about common errors and provide them with a list of those errors with accompanying codes. For example, a run-on can be “RU,” and you can use only that shorthand when commenting on a student’s work. Alternatively, you create a numbered list of common errors and write the number on a student’s paper, near the line where the error occurs. (See Resources – Common Errors for an example).

- Be selective about sentence-level errors. While proper grammar is important, it is arguably not as important as a student’s ability to construct a coherent argument, for example. Resist the urge to correct every error. See “Some thoughts on error correction” in the following section for more details about how to correct grammatical errors.

- Create a digital file with stock comments. If you find yourself making similar comments on papers (and you grade electronically), consider creating a list of common comments that you can copy & paste into each student’s paper. Be sure that the comments are phrased in a general way so they will apply to any student’s paper. To avoid writing vague comments, consider highlighting a spot in a comment to tailor to each student’s paper. Example:

- Remember to also link your analysis of strengths and weaknesses to the audience. For example, would this particular audience be more or less persuaded by these strategies? ßHere, you might fill in the highlighted space with a phrase specific to the student’s paper, such as “your audience of young sports enthusiasts.”

- You can create macros in Word or use Turnitin’s comment function, or you can just copy and paste common comments from one Word document to the student’s paper. These practices are demonstrated in the WAC Workshop.

Composition studies scholar Doug Hesse (n.d.) has suggested giving students “vouchers” in classes with multiple writing assignments. These vouchers are good for one detailed round of feedback per semester, during which the instructor commits to reading the paper as he or she would read a manuscript submitted to a journal. This is another potential approach for managing feedback expectations and ultimately your time.

Types of Feedback

There are various ways for you to offer feedback to students on their writing. Most writing instructors use a combination of these approaches:

Rubrics

Rubrics are not for everyone. Some teachers find them too formulaic, and some find them to require more time rather than making grading more efficient. You are not required to use a rubric to grade students’ writing in your W course; however, many students appreciate understanding how they are going to be graded and having some common vocabulary to talk about writing. There are a variety of ways to construct rubrics that will match your teaching and grading style while proving useful to students. Here are some steps for creating a rubric:

- Jot down notes about the goals of the assignment, what you’ve taught students thus far, and what writing styles, research processes, etc., are valued in your field.

- Look at strong examples of the genre you are asking students to create—such as a lab report or business plan. Note what makes the example strong.

- As you jot down notes, start identifying connections between concepts. How could you group concepts together? For example, “formal tone,” “precision,” and “effective transitions” could all be grouped under “style.”

- Try to group the important criteria around 4-5 main headings and assign points or labels for strong to weak writing within each criterion.

- A variety of examples can be found in the guide appendices and on the WAC Resources[RD1] Canvas site. In the workshop, we will discuss the strengths and weaknesses of these varied examples.

Some scholars also suggest that it can be useful to ask students to collaborate with you to create rubrics. (See, for example, Adsanatham 2013). University of New Haven instructors have had relatively good luck with this process. The key is to integrate the process early and as the instructor, reserve the final say in terms of shaping the rubrics.

Additional tips for rubrics

- Read rubrics with the class so that you can clarify any concepts or distinctions between categories.

- Ask students to grade a sample essay using the rubric and discuss their findings as a class.

- Use the rubric not to justify the grade but to help students see how their writing can be improved based on shared criteria.

Another use for rubrics is as a checklist, rather than a grading tool. Students use the rubric to understand the instructor’s expectations for the content and quality of assignments. This could be accompanied by a Grading Philosophy (see Resources – Grading Philosophy). and can be used to set expectations for all assignments in the class. See Appendix F for some sample rubrics. Also, see Resources – Rubrics for some sample rubrics.

Holistic Scoring

Holistic scoring involves assigning a grade to a student’s paper based on your overall impression—considering all criteria you believe to be important. In other words, you don’t break down a score into individual categories (organization, conventions) like you would with a rubric. You simply assign the paper an A, B, or so on—or an overall score, such as 6 (excellent), 5 (good), and so forth. Either approach works, and you might even consider asking students what they prefer. Holistic scoring generally takes less time in terms of grading, but you might receive more questions/concerns from students. A useful practice is to still offer a description of your expectations for effectiveness in the genre you are grading. (See Resources – Grading Philosophy for an example).

Models feedback

John Bean (2011), Professor Emeritus at Seattle University, advised that students often find models feedback more useful than John Bean (2011), Professor Emeritus at Seattle University, advised that students often find models feedback more useful than traditional marginal comments. Essentially, with models feedback, the professor collects an assignment (usually a short essay) and only grades by placing a letter on the assignment. The professor finds a strong example from the group of assignments and shows it to the class, discussing why it received an A. The instructor also discusses typical problem areas found in weaker essays (Bean, 2011, p. 314).

Some thoughts on error correction

Grammar instruction is a much-contested space in composition studies. At one time, it was commonplace for writing teachers to teach grammar in a formal way, requiring workbook exercises on punctuation and spelling and consequently correcting every error on a student’s paper. This model “has been largely discredited as a method of teaching composition to most writers” (Bean, 2011, p. 68). Studies have shown that teaching grammar does not improve student writing (Braddock, Lloyd-Jones & Schoer, 1963), largely because it displaces more important instruction. Yet, the most recent arguments in the field suggest that while it’s not a best practice to correct every error, it is still important to work with students on patterns in sentence-level errors.

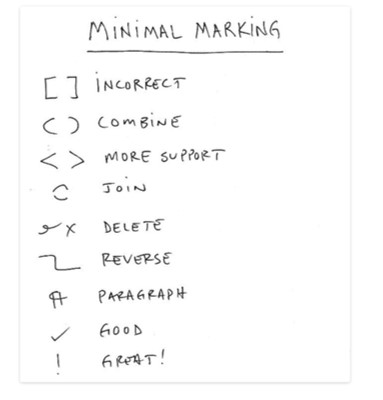

One reason why it’s not a best practice to correct every error is that correcting every error does not allow students to identify problems. Haswell (1983) discovered that students found and correctly fixed a majority of their sentence-level errors (comma splices, misspellings, etc.) when he moved from circling mistakes to putting an “X” in the margin next to the lines that had errors. This approach, sometimes called minimal marking, works best if you require students to correct their work before giving them a grade.

It might also be helpful to note that we tend to be more pre-conditioned to notice errors in our students’ writing. Williams (1981) embedded errors in professional writing and conducted a study; he found that the readers in his study noticed far fewer errors in professional writing than in student writing because teachers read student essays for the primary purpose of finding writing errors, whereas we read colleagues’ drafts for ideas. Is there a way in which we can change the way we think about our students’ writing so that we are reading for ideas and how those ideas are expressed rather than for error correction? Perhaps consider this question as you evaluate their writing.

Also, research has shown that students can catch more than 60% of their own errors if the students are taught to proofread their work and are held accountable for standards of correctness (Porte, 1988). (This is a good example of the type of expectation to set in a grading philosophy. See Resources – Grading Philosophy for some examples). Here are some different strategies writing teachers use to help students find their own errors and hold them accountable:

- Look for the most common grammatical error the student writer makes. Correct one (or model a different sentence) for the student and ask the student to find the other errors. (You’ll likely have to hold them accountable—with a graded assignment or a new draft due—to ensure they do this.)

- Mina Shaughnessy (1977) found that sentence-level errors are systematic and identifiable. What may appear to constitute many errors may actually be a few different instantiations of the same underlying issue.

- Mark up one paragraph or one page and ask the student to find errors throughout the rest of the paper based on your markups.

- Use symbols (minimal marking) or common terms developed by the class as short-hand to show common errors. Consider putting those symbols at the end of the sentence with the error and asking students to find their errors.

- Below is an image of a minimal marking system from Laurence Musgrove, professor and chair of the Department of English and Modern Languages at Angelo State University:

- Use a style sheet, such as the example provided in Resources – Common Errors.

- Encourage students to read drafts out loud. Many studies support the notion that students catch many errors through this approach.

- Find ways to encourage drafts. Errors disappear as students write multiple drafts.

- Help students understand that sloppy writing makes them look unprofessional.

- In interviews with business professionals, researchers have found that businesspeople are bothered by writing errors. Errors can affect readers’ impressions of the writer and readers’ understanding of the importance of the document (Beason, 2001; Hairson, 1981; National Commission on Writing, 2004).

Effective marginal & end comments

Even if using a rubric, most teachers also write comments on students’ papers. Commenting shows that you care about helping the student improve, but there can actually be problems with over-commenting. Research demonstrates that students become overwhelmed and confused by too many comments on their work (Sommers, 2013). With that in mind, here are a few best practices for commenting on student writing:

- Focus on higher-order concerns first—meaning, prioritize larger issues such as claim and evidence over grammatical issues. If students have to revise their claim, there’s a good chance that the sentences you mark up for grammar may not exist in a new draft.

- In a WAC assessment study of 64 student writers, the researchers found that effective revisions correlate with comments that address substantive matters (argument and evidence) rather than surface errors (ex: syntax and grammatical issues) (Wingard & Geosits, 2014, n.p.)

- Comment to inspire revisions (allow rewrites, comment on drafts, comment before a conference, etc.). The purpose of commenting should really be to help students think about how they would revise, rather than to justify a grade.

- Look for patterns. Rather than correcting every one-off error a writer makes, look for patterns in the writing that you can help resolve.

- Consider offering comments on early drafts and leaving minimal feedback on final drafts.

- Try to maintain a positive tone. Studies of students’ reactions to instructors’ feedback on their writing shows, not surprisingly, that criticism tends to make writers shut down and not want to revise. A good approach is to make sure you tell student writers what they’ve done well, too, which they do learn from.

- Use dialogic feedback, asking genuine questions that are spurred from students’ writing.

- Create a common language with students to talk about writing. Nancy Sommers (2013) described how her students began using the term “facing the dragon” to talk about moving beyond clichés and uncovering the complexity of a topic (p. 8). This common language can become part of the way you respond to student writing.

- Write comments in a way that will help students with future assignments as well.

- Consider writing an end comment that sums up the major items the student did well and could improve upon. The general advice is to offer no more than 3 major items for revision in the end comment.

- Consider a quiz or reflective writing that requires students to talk about your comments on their writing. This will encourage them to actually read your feedback and will help resolve any confusion they may have about your comments.

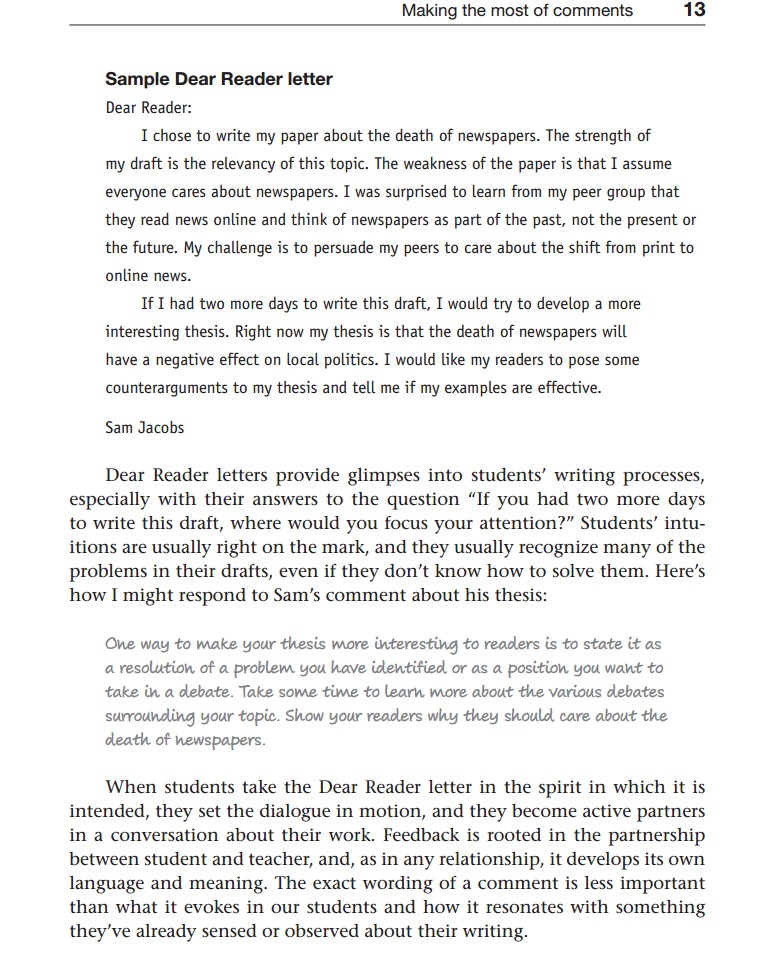

Nancy Sommers (2013), who conducted a longitudinal study of student writing at Harvard, has suggested that the “dear reader letter” is one of the best ways of engaging students in a dialogue about their writing. She asks students to write her a letter, describing their draft for an assignment. She asks them to describe what they believe to be the strengths of their writing on this assignment and what some of their perceived problems are (Sommers, 2013, pp. 12-13). (The instructions for the dear reader letter depend on the type of assignment and at what stage in the writing process students are being asked to submit the letter.) Sommers uses this letter, responding to students’ specific concerns when she writes them feedback. Below is a sample from her book, Responding to Student Writers.

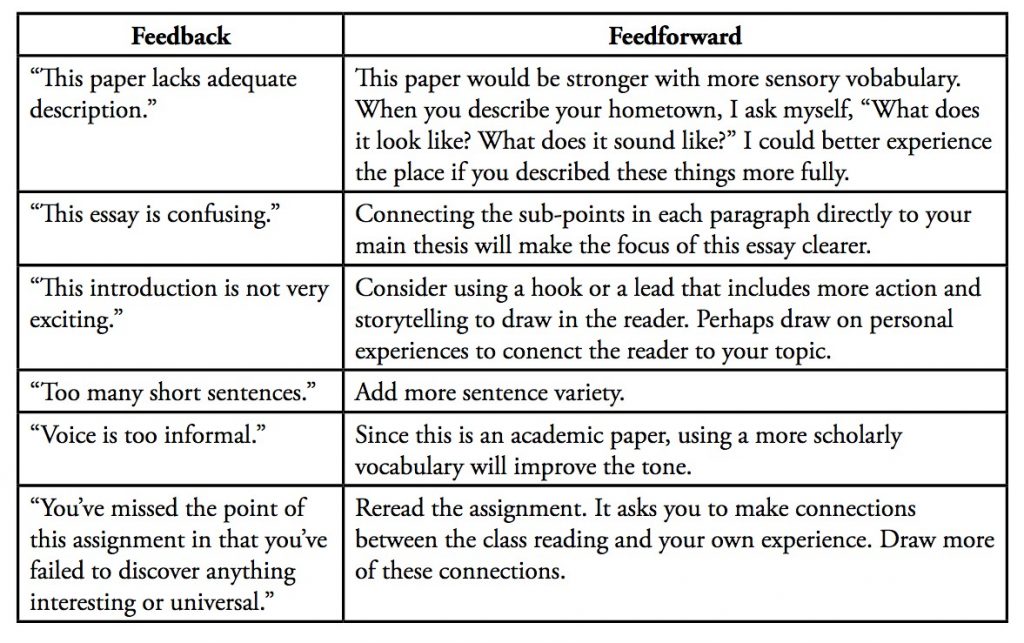

One last note on feedback: Writing Center directors Sheri Rysdam and Lisa Johnson-Shull (2015) have recently argued for the concept of feedforward, which they noted is “hidden in the discourse of other disciplines and in UK conversations about composition” (p. 70). Feedforward means that feedback should focus on ways the author can improve. Thinking about feedback as feOne last note on feedback: Writing Center directors Sheri Rysdam and Lisa Johnson-Shull (2015) have recently argued for the concept of feedforward, which they noted is “hidden in the discourse of other disciplines and in UK conversations about composition” (p. 70). Feedforward means that feedback should focus on ways the author can improve. Thinking about feedback as feedforward, they suggested, allows us to move past responses that focus on errors and awkwardness in a student’s writing to articulating guidance for future performance. They conducted a content analysis of around 1,000 student essays, looking at teacher feedback on students’ work. They categorized types of feedback including guidance for improvement, praise, and correction, and they found that most instructor feedback is negative and focuses on sentence-level errors. More importantly, they argued that these kinds of feedback are not helping students become better writers. By thinking about feedback in terms of feedforward, we are not denying the “reality of past or present performance,” they claimed, but we are sending “a positive message” because our comments are assuming opportunity and capacity for improvement (p. 81). Below are some model comments:

Grading Student Writing

While we have covered ways of responding to students’ writing and strategies for developing grading criteria, we haven’t necessarily described how to assign grades to students’ writing, which is something quite a few faculty members have indicated as a concern.

There isn’t one right answer to how you grade writing, and as much as we would like for it to be fair and objective, grading writing is not the same as grading a multiple-choice test. One of the best practices you can adopt is to set clear criteria. Even if you don’t use a rubric, consider giving students a checklist or walking them through a sample paper and discussing the grade you would assign it. Consider determining how much clarity is worth versus having a sound understanding of course content (form versus content) and consider expressing that to students in the rubric or checklist. Also consider a grade norming activity with students. If you do this, you might want to walk them through identifying strengths and weaknesses of a sample paper and then trying to evaluate it.

Also, some suggest that we should grade writing on simpler scales: a three-point scale of Excellent/Satisfactory/Unsatisfactory or a four-point scale of Excellent/Good/Developing/Needs Significant Improvement. While these concepts are somewhat subjective, they are perhaps easier to digest than A+, A, A-, B+, B, B- and so forth. Of course, you still have to assign an overall grade to students, but some faculty simply give A’s, B’s, C’s and below, rather than assigning the pluses and minuses. Additional grading strategies are discussed in the WAC workshop.

Alternative Grading Approaches

There are other approaches to grading that take a different spin on some of the issues we’ve discussed thus far.

1. Portfolio Assessment – Some argue that writing portfolios can simplify assessment and grading, and they can provide a valuable reflective experience for students. At a basic level, a portfolio is simply a collection of a student’s writing from throughout the semester. Most teachers aim to collect all evidence of revision, such as early drafts with instructor feedback and peer reviews. These materials can be collected digitally or in print. Some instructors do not assign grades on writing assignments throughout the semester and instead meet with students for a writing portfolio conference near the end of the term to assign a grade. Others make the final portfolio a percentage of the overall grade. No matter your approach, reflection is often key to portfolios. Ask students to reflect on the writing they did over the course of the semester; what they learned from your feedback and peer review; and how they used class lessons to compose effective work. See Appendix C for a sample portfolio assignment sheet (created by Kevin Barents).

2. Contract Grading – Contract grading involves an agreement between students and professors. Often, students are guaranteed a certain grade if they meet certain criteria. Some argue that this approach lessens complaints about grading and encourages students to engage more in writing as a process. Peter Elbow and Jane Danielewicz’s (2008) well-known grading contract is as follows:

“You are guaranteed a B if you:

1. attend class regularly—not missing more than a week’s worth of classes;

2. meet due dates and writing criteria for all major assignments;

3. participate in all in-class exercises and activities;

4. complete all informal, low stakes writing assignments (e.g. journal writing or discussion-board writing);

5. give thoughtful peer feedback during class workshops and work faithfully with your group on other collaborative tasks (e.g., sharing papers, commenting on drafts, peer editing, on-line discussion boards, answering peer questions);

6. sustain effort and investment on each draft of all papers;

7. make substantive revisions when the assignment is to revise—extending or changing the thinking or organization—not just editing or touching up;

8. copy-edit all final revisions of main assignments until they conform to the conventions of edited, revised English;

9. attend conferences with the teacher to discuss drafts;

10. submit your mid term and final portfolio.

Thus you earn the grade of B entirely on the basis of what you do—on your conscientious effort and participation. The grade of B does not derive from my judgment about the quality of your writing. Grades higher than B, however, do rest on my judgment of writing quality. To earn higher grades you must produce writing—particularly for your final portfolio—that I judge to be exceptionally high quality.

We use class discussions to explore the student’s notions about what constitutes “exceptionally high quality” writing, and we can often derive our criteria from students’ comments. We try to make these criteria as public and concrete as possible—often providing handouts and feedback relevant to these criteria. But we don’t profess to give students any power over these high-grade decisions…So we don’t get rid of grading entirely, but our contract radically reduces it. Throughout the semester we use only three possible grades: not satisfactory for B, satisfactory for B, and better than B. We don’t distinguish among grades higher than B till the end of the semester, when we have student portfolios in hand.” (Elbow & Danielewicz, 2008, pp. 1-2)

3. Involving Students – Scholars argue that teaching students how to assess their own work helps students become better writers. Researcher Jessica Riddell (2015) engaged students in analyzing the work of previous students using a pre-determined rubric. She graded students on their ability to effectively analyze others’ work and gave them feedback on how to mark papers more effectively. She then asked them to assess their own work based on what they learned from the process. 95% of students strongly agreed or agreed that getting feedback on how to effectively assess essays helped them revise their own essays and prepare for future writing tasks (Riddell, 2015, p. 85). Students liked that they were able to understand how instructors grade. As they read other students’ essays, students noted that they discovered mistakes they made on their own essays. It’s also interesting to note that students categorically gave themselves lower marks than their professors (5-10% lower). Instructors have found students who participate in the grading process complain less about grades because they seem to understand the evaluation process better.

4. Ungrading – Ungrading is a movement away from the traditional model of instructors assigning grades to student work. It challenges both students and instructors to find a new way of measuring learning and encourages students and instructors to work as partners in learning. Ungrading focuses on formative feedback and student reflection of their personal development. Read more about ungrading via the following sources:

- Ungrading: An Introduction – University of Denver professor Jesse Stommel has been practicing ungrading for over 20 years. He offers a detailed overview of the approach.

- Toward a Non-Dogmatic Pedagogy: On Susan D. Blum’s “Ungrading” – A book review from the Los Angeles Review of Books describes the theory behind ungrading. We also recommend the full Ungrading book.

- Entering the feedback loop: Robert’s origin story – Robert Talbert, a mathematics professor at Grand Valley State University, describes his journey into alternative grading: how it was inspired, what he did to change his approach to grading, and why he’s never going back to points-based traditional grading.

References

Adsanatham, C. (2012). Integrating assessment and instruction: Using student-generated grading criteria to evaluate multimodal digital projects. Computers and Composition, 29, 152-174.

Bean, J. (2011). Engaging ideas: The professor’s guide to integrating writing, critical thinking,and active learning in the classroom. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Beason, L. (2001). Ethos and error: How business people react to errors. College Compositionand Communication, 53(1), 33-64.

Braddock, R., Lloyd-Jones, R. & Schoer, L. (1963). Research in written composition. Champaign, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Elbow, P. & Danielewicz, J. (2008). A unilateral grading contract to improve learning and teaching. English Department Faculty Publication Series, Paper 3, retrieved from http://scholarworks.umass.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=eng_faculty_pubs

Haswell, R. H. (1983). Minimal marking. College English, 45(6), 600-604

National Commission on Writing. (2004). Writing: A ticket to work or a ticket out. Retrieved from http://www.collegeboard.com/prod_downloads/writingcom/writing-ticket-to-work.pdf

Riddell, J. (2015). Performance, feedback, and revision: Metacognitive approaches to undergraduate essay writing. Collected Essays on Learning and Teaching, 8, 79-95.

Rysdam, S. & Johnson-Shull, L. (2015). Introducing feedforward: Renaming and reframing our repertoire for written response. Journal for the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning, 21(1), 69-85.

Sommers, N. (2013). Responding to student writers. New York, NY: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Williams, J. M. (1981). The phenomenology of error. College Composition and Communication, 32(2), 152-168.

Wingard, J. & Geosits, A. (2014, April 6). Effective comments and revisions in student writing from WAC courses. Across the Disciplines, 11(1). Retrieved December 6, 2016, from http://wac.colostate.edu/atd/articles/wingard_geosits2014.cfm

What I like to do is have one-on-one conferences to discuss drafts in lieu of the students actually submitting actual drafts for me to read through. The student will share the draft on the Zoom screen, and we will have a discussion from there.