A key pedagogical concept in composition studies is that teachers should help students understand that writing is a process—meaning writing involves a series of stages. While there are different theories on how many phases there are and what the phases should be called, for our purposes, we’ll use the following: (1) Pre-writing or brainstorming, (2) Drafting, (3) Revising, (4) Editing. As you can see from the list of phases, revision is not the same as editing. Editing is proofreading—checking for minor errors such as punctuation mistakes. Revision is a much broader process that often requires a significant amount of re-writing. Students should start revising by thinking about higher-order concerns such as claim and evidence. Paragraph transitions and grammar can come later.

It is important, as a W instructor, to allow students time to engage in these phases. If you can build these stages into your syllabus, that will help students avoid writing at the last minute. In planning, it is important to keep in mind that post-process composition theory recognizes that these stages are part of a recursive process. In other words, students often do not move linearly from one phase to the next but participate in multiple phases at different times as their process moves forward. (Their process also varies depending on the type of writing they are assigned.)

This notion of writing as a process is a bit hard to scaffold into a syllabus, but you might consider asking students, for example, to come to class with a page worth of work to show progress—but not necessarily asking for an introduction or conclusion. Try to give them some freedom to compose in a non-linear manner if it works with the structure of your course.

Keep in mind, too, that you do not need to grade every piece produced in the stages of the writing process. In fact, some students will find that being graded inhibits their progress.

1. Brainstorming

Brainstorming is often underrated. Allowing students to take the time to come up with a specific, well-thought-out idea in the beginning can often yield a more successful assignment. Research in the field of Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages has found that brainstorming allows students an opportunity to stimulate the thinking processes, develop ideas, and organize their thoughts into a logical order (Rao 2007). Brainstorming also provides a low-stakes opportunity for students to wrestle with their content knowledge and opinions.

To engage students in brainstorming, you can set up paired interviews, where you create questions students can interview one another with, such as: (1) What problem is your paper going to address? (2) Why is this problem significant or controversial? (Bean, 2011, p. 293). Some teachers do free association whole-class discussions on certain topics. Example: Use the phrase “election 2016” and see what words pop into students’ heads. Start writing the words down and grouping them into categories. You may see tensions or similarities emerge that begin to help students identify controversial topics worth exploring in a paper. Even giving students time to freewrite in class or asking them to freewrite for homework can be useful. The Writing Center at UNC Chapel Hill describes a “cubing approach” that asks students to explore a topic from six modes:

- Describe it.

- Compare it.

- Associate it.

- Analyze it.

- Apply it.

- Argue for and against it.

Clearly, approaches will differ depending on the assignment and discipline.

2. Drafting

In drafting, the writer moves from brainstorming ideas to putting those ideas into words, sentences, and paragraphs. Some instructors may decide to require students to take notes or outline their paper first in order to help with structure. Some may ask for a thesis statement and three supporting points of evidence—depending on the genre of the paper. One of the best ways to make sure students draft ahead of time is to build it into your homework assignments. Requiring students to submit items at different stages in the writing process can help keep them on track. This does not mean, however, that you have to read, grade, and comment on everything they submit. You might choose to just walk around and check their progress (lingering long enough to ensure the draft they’re showing you isn’t for another class!) while they are working on an in-class activity.

3. Revising

we’ve mentioned, one mistake students often make is thinking that revising is the same thing as editing. Revising is about thinking big—questioning if the thesis is making an original argument; ensuring that the evidence supports the argument; examining the coherence of paragraphs. As students revise, encourage them not to focus on smaller, sentence-level issues such as comma errors—yet. Make them aware that if you’re conferencing with them or conducting peer review, they may need to spend a significant amount of time rewriting their work. Also, try to map out time in your class schedule for them to do this. In other words, build the stages of the writing process into your syllabus. We suggest building draft dates into your syllabus and putting those draft dates on your assignment sheets. You might consider adding in required or optional writing center consultations and time for students to share their writing or discuss ideas.

One of the biggest challenges of both drafting and revising is actually getting students to write something well before the day an assignment is due. Aside from the above suggestion about asking students to bring in drafts of their progress, you can also try the following:

- Peer review (in class or for homework) – See Best Practice for Revision for strategies.

- Conferences – See Best Practice for Revision for strategies.

- Require that students submit a draft and a final version of their essay when they submit the final paper, and consider including revision as a category on the rubric.

- Require or encourage students to attend a Writing Center session before submitting their final draft.

- Show students a draft of something you’re working on and demonstrate that writing can be a sloppy, complex process, or show them a draft and final version of a student’s paper from a previous semester to help them understand what you mean by revision.

- Give substantive feedback on drafts rather than final papers.

4. Editing

Now, we finally get to proofreading. Editing is about finding all of those sentence-level errors that can plague drafts. Here are some tips that often work for students and teachers alike:

- Look at the paper in a new way. Whether you print it out, increase the font, or change the color, find a way to make the paper look different visually. You are more likely to catch errors this way because the paper looks foreign to you.

- Get some distance. Advise students to build in some time to step away from their work and come back to it (which they can’t do if they’re writing up until class begins). They won’t all take your advice, but those who do will find that they’re able to re-think the paper once they’ve taken a step away from it.

- Read backwards. Some suggest that reading sentences or paragraphs backwards helps to catch small errors such as misspellings.

- Don’t mix content with form. Let your students know that if they’re still struggling with their argument or even the wording of a sentence, they’ll be less likely to catch grammatical errors because their brains are reviewing for more than one thing at a time. Ask them to try a final run-through that only focuses on proofreading.

- Read out loud. Some also find that reading out loud helps them proofread their work.

5. Reflection

We consider reflection to be an important part of the writing process. Asking students to reflect after turning in an assignment can help with metacognitive awareness and transfer. The WAC Clearinghouse suggests that students who reflect on their writing improve their ability to critique their own work. The types of questions you might ask students to reflect on depend on the assignment. You may ask students to reflect on:

- their intended audience for the paper – Who is the audience? How did the student cater the piece of writing to this audience (tone, organization, background information, etc.)

- inclusion of course concepts – how did they integrate course content (writing- or discipline-related) to compose an effective deliverable?

- You can ask students to use specific examples or even quote their own writing.

- what they have learned from completing this assignment overall.

Dr. Jason Hope from the United States Military Academy created an effective prompt to encourage students to reflect on their personal experience in completing a writing assignment.

Here is an example of a reflection prompt given to students after they have received a grade with feedback:

One of the best ways to improve as a writer is to actually use feedback as you look ahead to the next writing challenge or endeavor. So, this reflection assignment is designed for you to read, think about, and make a plan for using the feedback on your graded Assignment One paper and to help you with your next paper. Please answer the following questions for this reflection, which should be in full sentences amounting to approximately 300 words:

- What strengths do you realize that you have as a writer given the feedback you received?

- What challenges do you realize that you have as a writer given this feedback?

- What part of your process yielded good results for you?

- What do you wish you did for this paper as part of your process?

- What strategies would you implement for your next paper to build on your strengths and meet challenges?

A few additional resources:

- The WAC Clearinghouse offers some background on the benefits of reflection and an extensive list of resources by discipline.

- A series of student reflection prompts from the University of Waterloo encourages students to reflect on their assignment experience using specific sentence frames.

- I was surprised/pleased/disappointed/already knew that . . .

- I felt most successful as a learner or group member when . . .

- I felt least successful as a learner or group member when . . .

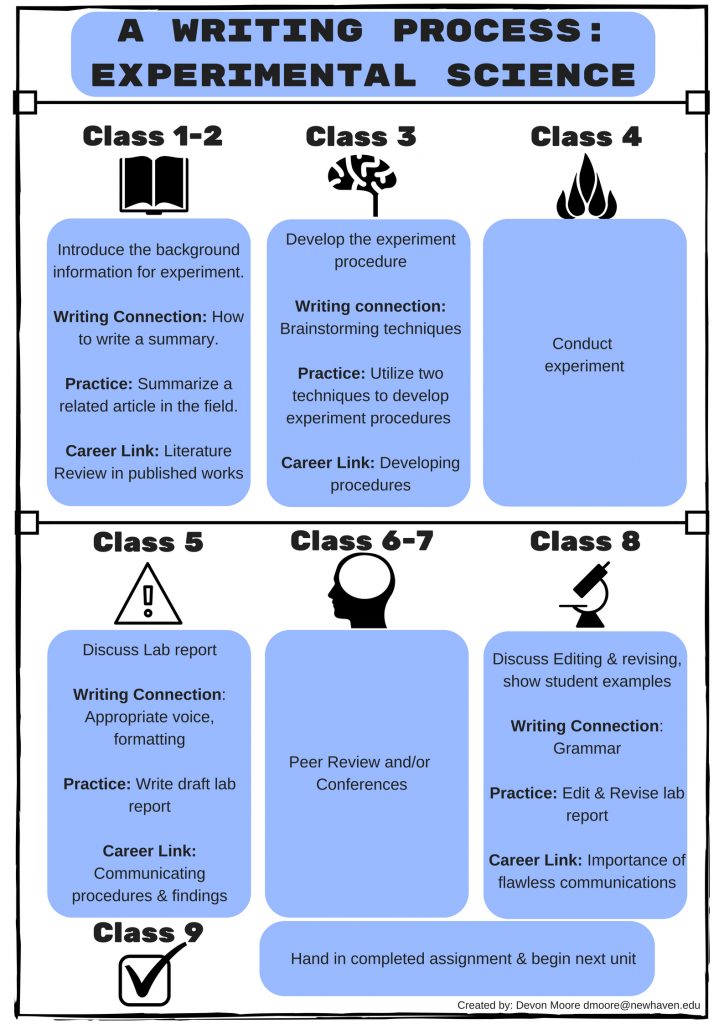

An important part of helping students understand that writing is a process is scaffolding that process into your daily schedule. Below is a sample of how to scaffold the writing process into experimental science.

Bean, J. (2011). Engaging ideas: The professor’s guide to integrating writing, critical thinking,and active learning in the classroom. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Pingback: Welcome to Writing Across the Curriculum