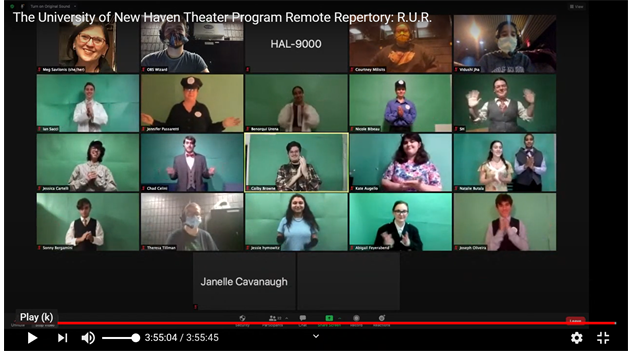

Welcome to the inaugural production of the University of New Haven Theater Program’s Remote Repertory.

Fall 2020 marks a new chapter in live performance for the Theater Arts Program at the University of New Haven. As theater practitioners around the world contend with the restrictions of public health and safety measures necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic, attempts to re-imagine theater and live performance have led to innovative and resourceful uses of a wide range of technologies. For the last several months, the cast, crew, and production team for our production of Karel Čapek’s R.U.R. have been learning new skills and overcoming challenges with ingenuity and resilience. Their commitment to forging creative paths in the realm of “virtual theater” while bringing this 100-year-old script to life embodies the University of New Haven’s commitment to experiential, collaborative, and discovery-based learning.

On this project, we have explored a variety of “what-if”s and “is it possible to”s. One line of inquiry focuses on the text itself: What new ideas and insights can

our team bring to a 100-year-old play, originally written in Czech, to make it a story that is appropriate for and relevant to our audience? (It turns out we were not alone in our interest in revisiting Čapek’s play on its anniversary. Check out this story at Radio Prague International about the exhibition A Journey into the Depths of the Robot’s Soul at the Karel Čapek Memorial through February 2021.) Simultaneously, we have had to investigate how to tell this story. Of course, these tracks are ones theatre artists always operate on, but producing live theater since March 2020 has seen an exponentially increasing array of both challenges and possibilities.

Among our achievements, stage manager Theresa Tillman, along with her assistant stage managers Vidushi Jha and Courtney Milisits, has developed new rehearsal room management strategies, whether enforcing COVID protocols when actors were sharing a space or facilitating operations when everyone was in their own space; Janelle Cavanaugh (a first-time set designer) not only conceived of a virtual set but also learned how to use rendering software to create it. Costume designer Caston Otersen came up with creative solutions for creating a wardrobe for a 15-cast-member period piece without having access to our shop’s technology. Barry Libowitz, a first-time dramaturg, investigated methods for delivering dramaturgical materials to the cast and crew digitally and worked on creating digital audience interventions—including arranging a post-show discussion via Zoom. Colby Adams—taking on the roles of lighting designer, sound designer, and livestream programmer, worked diligently to train the cast on setting up sound and lighting technologies in their individual performance spaces while also learning how to set up and operate our Zoom-to OBS- to YouTube livestream. And, last but certainly not least, our cast has had to learn new acting techniques, wrangle with spotty wi-fi connections, and function as an ensemble from the confines of their Zoom boxes.

Indeed, it is the “how” of it all that has afforded our company the most significant

challenges, as well as yielding the most impressive solutions. The trial-and-error process can be daunting when your laboratory is off-limits and you have to learn new tools and methods while still meeting your “publication” deadline. As we move from the private realm of the rehearsal hall to the public platform of YouTube, whether we have solved all of our problems or not, I am inspired by the risks everyone on the R.U.R. team has taken. And although we might not achieve all of the goals we have set for ourselves, as an educator, I concur with Kathryn Schulz, who argues, “Far from being a sign of intellectual inferiority, the capacity to err is crucial to human cognition. Far from being a moral flaw, it is inextricable from some of our most humane and honorable qualities: empathy, optimism, imagination, conviction, and courage. And far from being a mark of indifference or

intolerance, wrongness is a vital part of how we learn and change. Thanks to error, we can revise our understanding of ourselves and amend our ideas about the world.” [1] To be sure, Čapek’s apocalyptic text is itself a rumination on error and the human condition that encourages audiences to “amend our ideas about the world,” and I hope our creative reimagining of it, in all of its glorious imperfection, opens a space for a similar amending of our ideas about what theater is.

[1] Schulz, Kathryn. Being Wrong: Adventures in the Margin of Error. HarperCollins, 2010. p. 5.