Video games under the role-playing genre are some of my favorite time killers, ever since I was younger. The opportunity to enter a rich fantasy world with tight combat, colorful characters, along with the rich exploration of these crafted worlds full of grand landscapes. From the monolith series of the genres, such as Chrono Trigger or Dragon Quest, to the more obscure choices like Triangle Strategy and Ni No Kuni, I’ve explored my fair share of fantasy worlds where magic is a staple and monsters roam aplenty. After exploring enough of these bountiful lands, a kind of compliance can arise, where each world feels like only slight variance on the same base set of ideas. Role-Playing games (RPGs) have thus created an easy set of conventions to criticize, from the nonsensical logistics of a player’s capabilities, or the almost mandatory hours one dedicates to walking in the same area to grind for experience when the game’s difficulty randomly spikes.

It’s within this sphere of stagnation that prompted the Japanese company Love-de-Lic, to look inwards and begin production on what now seems to be described as an “Anti-RPG.” This game, which originally only hit Japanese shelves, was titled moon: Remix RPG Adventure, releasing on the PlayStation 1 on October 16th, 1997—coincidentally two weeks after what some would call the greatest RPG of all time, Final Fantasy 7, released on the same system. Due to some renewed interest in moon thanks to Toby Fox—creator of the wildly successful RPG Undertale—members of the original team would pair up with translators under the new banner of Onion Games to rerelease moon, this time to an international audience. With a promise of flipping the script on the typical RPG experience within a world not similar to any that came before it, I decided to venture in and witness what moon had to offer. What I found, just in under 6 hours of gameplay, was the hints of a truly rich world that delivered on the promises of granting RPG-fanatics a comedic look in the mirror wrapped up in a gorgeous blend of aesthetics and styles.

Two Perspectives of the Same (Moon) World

The most obvious aspect of moon‘s commentary and framing is established as soon as players hit “Game Start.” Once selected, players witness a cutscene of a young child up late at night, who sits down and begins playing a standard Role-Playing game. The player takes control and begins the prologue of the game, experiencing small portions of the world and the characters that inhabit it. For simplicity, the avatar a player controls in this section will be referred to as the “Hero,” a title the nonplayable characters in the game refer to this individual with. While controlling the Hero the player engages in combat against a handful of enemies, from the very first slime to the dragon who supposedly ate this world’s moon. The prologue follows most conventions for the specifically Japanese role-playing game genre, with tile-based movement, a magical medieval setting interlaced with modern inventions, the ability to freely loot random citizen’s homes for armor or other items, and anime-stylized portraits for NPCs. The child who’s currently playing through this standard quest is eventually interrupted amidst the final fight by their mother, telling them to turn the game off and go to bed. It’s when the child turns off the TV and it suddenly powers back on when things begin to shift, with the child investigating the screen only to then be sucked into the static. This whole 8~ minute section and the game itself experienced will be referred to as “Moon” to differentiate it from the actual contents of the primary perspective/style/gameplay of moon.

It’s from this point on the child and player have now crossed into the world of moon, or as the world’s Goddess dubs it when speaking to the child in a dream (with the confusingly simple name when trying to explore the many worlds of narrative), “Moon World.” Now stuck in Moon World, tasked by the Goddess to collect the scattered love across the land, the Child—a title that’ll now be used to parallel the entity of the Hero—gets to explore this fantasy environment not through the lens of a powerful warrior, but as a background character. The Hero still exists in this world, still on their slaughter-filled quest to slay the evil dragon, and the player now gets to witness the reality of all their supposedly great victories.

This recontextualization of the initial narrative and lens the player has from “Moon” comes extremely early in gameplay. When playing as the Hero, a player begins their quest by leaving a king’s castle, and engaging in a short bout against what’s depicted as a rabid stray dog. The dog flees before the Hero gets an attack in, and a player will then likely talk to the few townies in the square, who all offer praises to the Hero and wish them luck on their quest. However, when exploring this same moment in time as the Child—who at this point is invisible—the reality of this event is shown. Instead of the Hero being engaged by some crazed mutt, it is instead a dog belonging to a local grandmother (who assumes the Child is their deceased grandchild who somehow managed to survive a fatal accident). The dog, Tao, is seen simply walking around the town’s square, before being scared off by the attacking Hero. With this, the Child will be prevented from going to various areas as the Hero knocks them out of the way while ferociously chasing Tao.

With nowhere but south to go, players will likely take the time to talk to the four NPCs standing around a fountain, the same characters who wished the Hero luck in “Moon.” However, it’s made extremely evident that these characters both look and act drastically different. Curio, a pawnshop owner, is displayed in “Moon” as a rather rugged middle-aged man in a turban; as the Child, Curio is instead a rather shriveled looking raisin of a man in a long robe whose head is larger than his entire body. Meanwhile characters like Shambles, an old homeless man, wishes the Hero luck in “Moon,” yet as the Child a player will overhear him insulting the hero’s dim-witted dog chasing and groaning about if the Hero can actually defeat the dragon.

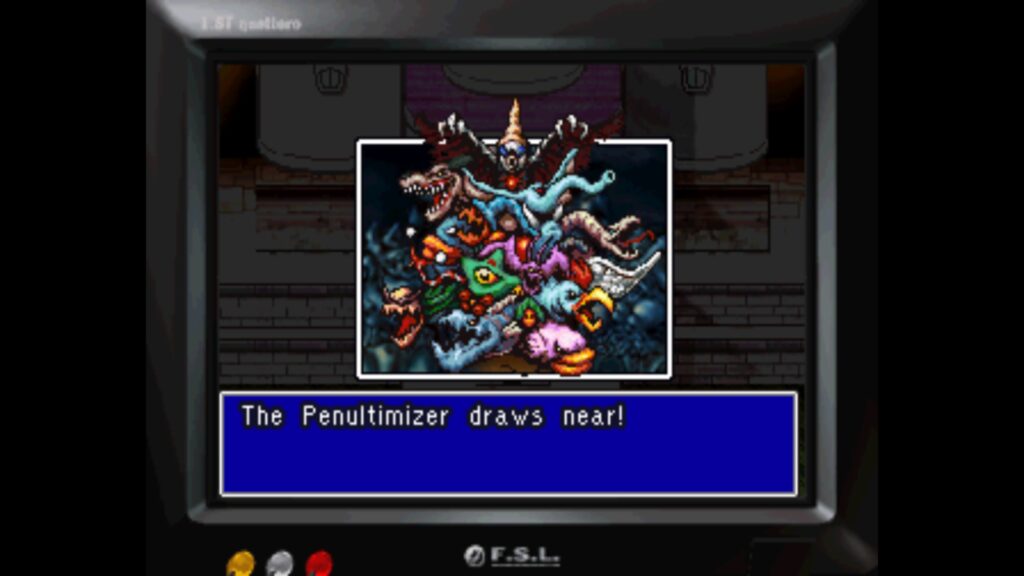

This warped sense of admiration the Hero believes the townspeople holds for them and their quest is a subject that’s torn down in similar ways across the rest of the game and makes a player ponder what the truth is behind the warped vision they experienced in the prologue. Continuously the Hero does what they believe is right due to their outright fabrications of NPCs’ dialogue. Most of this is done to satirize how players typically function in the world of other RPGs, and will be explored in a section further on. For now, it’s important to emphasize the way this encourages a player’s sense of curiosity and problem solving. As an example, the player-controlled Hero in “Moon” will eventually reach the Demon Castle, home of the dragon. Before entering the castle, the Hero engages a boss called “The Penultimizer,” a conglomeration of monsters seemingly stitched into a single foe. While a player likely won’t find any meaning to this during their initial playthrough, watching this section after even just a few hours of gameplay sparks interest for what the player has yet to witness. This is due to how the Penultimizer is made up of creatures from various sections of the game, which the Child revives to obtain love after the Hero kills them. For example, in the middle of the Penultimizer’s sprite sits a green starfish-like creature with a yellow eye in its center. Early in a jungle-themed area, a player will find this exact creature identified as “Sid Vitness.” Noticing that this monster from “Moon” is an amalgamation of various creatures one can revive, player such as myself will acquire an itch to figure out what each monster is, and keep an active eye out for the unfamiliar faces adorning the Penultimizer sprite. Comparing these aspects is even more rewarding as the artistic styles depicting these monsters are quite distinct, with the creatures in the prologue having more standard antagonistic fantasy designs with impressive sprite work, while the player will interact with these monsters in a much friendlier form, complete with a claymation style as opposed to clearly-defined pixels.

Absurdity of the World

While comparing how the world of moon stands up against “Moon,” it’s hard to ignore the countless oddities in the game’s presentation and clashing aesthetics that create a unique space to explore and learn about. JRPGs aren’t exactly a restrictive genre, even in the genre’s early break-out hits there were plenty of illogical combinations of magical creatures and innovative mechanical marvels. Yet moon still manages to soar above them with its absurd combination of environments. The most stand-out area in this case is easily a Western family’s house found in the game. Just past the humid jungle, east of a mute caveman, a player will stumble upon a modern suburban house—white fence and all—just seemingly plopped into the land. The Hero during the prologue actually was shown in this same area, but it was still portrayed in a less lavish American style than what the Child finds. Complete with a lawnmower and refrigerator, the house sticks out like a sore thumb. No attention is really given to how odd the American’s rather isolated presence is, the only notable comment regarding them is by their only neighbor, a crotchety traditionalist Japanese man who just complains about how loud they are and how annoying their slang is, yet said slang has already seeped into the old man’s own vocabulary.

The American House also is home to the other oddity that defines moon’s identity, which is its strong, distinct, but ultimately strange character designs. Touched upon earlier with Curio’s different designs in the Hero’s and Child’s eyes, moon is full of folk who range from rather normal humans to denizens who could qualify for monsters themselves. Housed inside the suburban house is such a creature named Pappas, a comic-creating father whose neck is long enough that it could likely crane his Clooney-rivaling Chin around a corner with ease. Modernity isn’t restricted to this forest pocket, but can be found dwelling in moon‘s caves. Characters such as Burrn aren’t as strangely proportioned as Pappas, but the sight of a wannabe-rockstar attempting guitar solos within a cave all the while selling CDs housed in garbage bins is far from expected of an RPG from ’97. It’s difficult to not enjoy the charm of these characters, such as how Burrn will be overcome with shyness if a player ventures too close, hiding his guitar and shifting to a more unassuming stance. But it’s when appreciating the absurdity, such as quietly and from a distance waiting on Burrn to succeed with his attempts at a solo, that a player is rewarded. In this case a monster’s spirit appears for capture and revival, fueling a player’s progression and ability to find people of interest like Burrn.

Even among the already fantastic world a player explores in moon, some situations stick out as stranger than they could expect. Such an oddity is found with during a side quest involving Baker, unsurprisingly a baker in town. After learning about his visits to the town bar on a specific day, a player will likely begin following this introverted fellow and watch him down drink after drink. When talking to the bartender Wanda, a player will then learn that when stuck in a stupor Baker tends to enter his house without locking the door behind him. Spurred on by the curiosity of investigating the backroom of the bakery, players will then stalk Baker on his walk home, following him inside. If done early enough, the player will find Baker’s clothes and a loaf of bread next to a large toaster, which is housing a small object. The surprise here might come off as obvious, that Baker is so passionate for breadmaking that he goes the extra mile to sleep in a toaster-themed bed. A relatively simple answer for a strange presentation.

However, this explanation is actually too simple. Instead, when the night is about to end, out pops out an entire loaf of fresh bread equipped with a mouth from the toaster, landing directly onto the awaiting orange scarf of Baker’s outfit. This loaf then begins to speak to the Child, realizing it’s been caught yeast-handed. Despite this unexpected turn, the speaking loaf then notes “Ain’t it obvious? Obviously, I’m a Breadsman.” The Breadsman doesn’t seem to want to truly elaborate on the absurdity of the situation, but recognizes it as still being a little alarming, asking the Child to not tell the other townspeople about his true identity. Yet the really disturbing fact is what the Breadsman says regarding the fact he sells his previous head each day, noting how “it delights me. To hear descriptions of ‘Delicious’ while I’m being digested.” At this point in their journey, a player may have themselves bought some bread from Baker as a means of recovering stamina, so the reveal is extra revolting as the thought of eating a sentient piece of bread recontextualizes all prior engagements with Baker and his goods. As the Breadsman notes that “Baker” forgets the truth of his existence every morning, the loaf’s appearance morphs back into the humble “man” the player first met, with this twist being a secret a player simply holds onto for the rest of the game. Can I or other players really hate Baker for this secret, when the man himself doesn’t know what he is? Is it worth it to buy the bread offered on sale from the baker who doesn’t even know how his goods are made? If his head is the standard loaf he sells, then what is the reality of the croissant that’s also stocked? All questions left without clear answers, just left to rattle in the heads of those who don’t just accept the absurdity and move on.

Moments such as the one described is what makes the world of moon so fascinating to dive into. Moon World is full of clashing levels of technology, odd blends of aesthetics, and varying degrees of “weird” infused into each of its characters. While some characters act normal, like the florist Flora, and other wear their strangeness on their sleeve, such as the religious zealot Adder, the fact that a character like Baker blends into the world so seamlessly encourages players to truly investigate each NPC and learn what they all have to offer.

A Player’s Immersion in the World

A major aspect of moon is becoming one with the world itself and the schedules of those who inhabit it. Certain events occur only on certain days or on certain times, so really engaging with the real-time passage of the game is essential to complete it. The digital manual, which was based off the original Japanese version, even advises players with a couple hints, such as how “Moon World is constantly changing with time. Sometimes it pays to be patient and wait. Put on your favorite MD [Music Disc] and relax” along with “spending a day following certain characters sometimes yields unexpected rewards” (23). Curio is an example of staying vigilant of the time, given how he’s the most versatile shopkeeper in the early section of the game. Visiting his shop during the day is helpful, allowing players to purchase a fishing rod, some bait, bones for Tao, and a promotional drawing of the Hero. These items aren’t awful, especially the rod and bait as they allow for ways to grind for Yenom—spell it backwards and guess what it is—but the other objects for sale leave a lot to be desired. However, if a player waits for the day to end, they’ll witness Curio slowly descend from behind the counter downstairs right to his bed on a different floor. If a player visits him in his bedroom quickly enough, they’ll be able to purchase a handful of more unique items, such as a magnifying glass or a chloroform-soaked rag. Such specific items are pivotal for other quests in the game and is a simple yet great way of demonstrating how memorizing the schedules and behaviors of the various characters in moon will help a player progress.

However, moon also encourages a player to create this kind of schedule for themselves. The previously mentioned bait sold by Curio is really useful as fishing is a renewable way of making Yenom, but buying individual bait for 10 Yenom for what’s initially only a 60~ Yenom return doesn’t feel too profitable, especially as walking to and from Curio’s shop and the fishing lake does burn a decent portion of a day away. A player can catch word, or simply discover if lucky enough, about how on certain days an area will have the bugs used as bait spawn infinitely as long as the sun is up. This spot is thankfully just a single screen away from the lake and makes it easy to plan certain days entirely on burning daylight running around capturing bugs, then fishing in the moonlit lake. As certain quality of life items can start to put an annoying dent in one’s wallet, dedicating an entire day to activities such as this can yield bountiful benefits. It’s after doing these plans a couple times that a player may discover they’ve become no better than Bilby, a guard at the castle who spends one day a week flying paper airplanes. While most action RPGs that moon is parodying will have players thinking critically on how best to optimize characters for combat, moon instead has players strategize on how best to tackle each day, how to reach relevant characters at the right time, and how to manage their inventory to get them where they need to be.

Just the Surface

As I’ve been likely made evident through this analysis of moon, the game is a rich tapestry of unabashedly weird characters, and filled to the brim of strange moments that still enrapture me and get me immersed. Despite how early in the adventure I am, and frankly how lost I can be at times, I still find myself loving the characters of the world, and rush all around the areas open to me. With reveals like Baker’s identity, or the fun minigames presented by characters like Adder, to the weirdly recognizable cut-up English voices used for NPC dialogue, along with the absurdist humor, I thoroughly enjoy moon‘s spin on a genre I’ve dedicated hundreds of hours engaging with. While the comedy or premise of the game might be a bit tired according to cynics who’ve witnessed the many animations online critiquing RPGs, an appreciation for the very unique vessel these possibly tired remarks makes it still feel fresh and new. Without looking deeper into the game’s development, moon could’ve been passed off to me as a nostalgia-fueled project by modern developers who just nailed the aesthetic, but learning its past and the positivity and love the small team once had and has since found again makes the experience all the more magical. While the beauty of moon can be rather subtle at times, the atmosphere and artistry on display in this world born of satire is bountiful and should be experienced.

Works Cited

“ABOUT US Archives – Onion Games.” Onion Games, oniongames.jp/about-us. Accessed 10 Feb. 2024.

Klepek, Patrick. “A Game Without Killing: The Story of Moon’s 22-Year Journey to Leave Japan.” VICE, 31 Aug. 2020, www.vice.com/en/article/m7jw78/a-game-without-killing-the-story-of-moons-22-year-journey-to-leave-japan. Accessed 15 Feb. 2024.

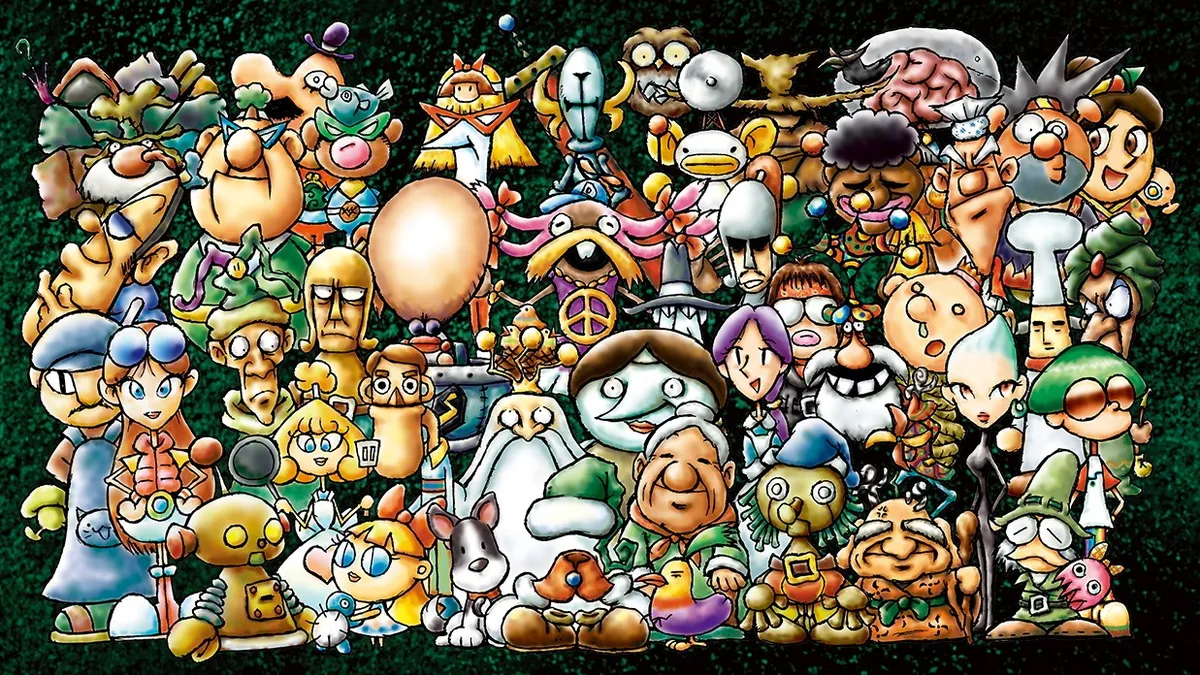

Featured Image

Artwork Depicting moon‘s Cast by Kurashima Kazuyuki