“Me? My time is brief, so I love life with greater urgency than most. I don’t fear death, I just feel that I haven’t gotten any pleasure out of life. I want…all I want is to be happy.”

Ding Ling 56

Reading “Miss Sophia’s Diary” was a pleasure I haven’t really gotten from reading in a long time. Ding Ling’s creation of the character Sophia feels so genuine and real in a way that I haven’t seen with female characters in a long time. Sophia’s rudeness is not her simply being a horrible person, rather it is her being too afraid to act upon her true feelings and reveal herself as weak for admitting that she is human. Sophia is trying so desperately to appear strong and above everyone else—perhaps as a way to stand above her illness—and because of that, she alienates her true self from the people who she claims are her friends. Thus, even when surrounded by people, she feels alone; and so she can only confide in the pages a book that only she was ever intended to see. Her diary, and therefore her self-reflective dramatic and rude-seeming emotions, are her only way to share what she is really feeling, to express her pains without fear of judgment, and so we get this unadulterated look at what a woman really is.

One moment that struck me in regards to Sophia pushing people away was how she attempted to force away Ling Jishi—the object of her lust—to make a fool of him so she wouldn’t seem weak for being head over heels as they look at a photo of her niece:

“By that time I’d finished washing my face and was sitting at the end of the table. He looked at me and then back at the little girl, then at me again. It’s quite true. She does look a lot like me, so I asked him, “Cute, isn’t she? Does she remind you of me?”

“Who is she?” There was unusual earnestness in his voice.

“Tell me, don’t you think she’s cute?”

He asked again who she was.

Suddenly I realized what he meant by the question, and I had an impulse to lie about it. “She’s mine.” I snatched the photograph and kissed it.

He believed me. I made a fool of him. My lie was a complete success. His seductiveness faded in the face of my triumph. Otherwise how—once he’d revealed such naiveté—how was I suddenly able to ignore the power of his eyes and become so indifferent to his lips? I had triumphed indeed, but it cast a chill over my heated passion. After he left, I was consumed with regret for all the obvious chances I’d let slip away. If I’d shown more interest when he pressed my hand, if I’d let him know I couldn’t refuse him, he’d have gone a lot further. I’m convinced that if you dare to have sex with someone you find reasonably attractive, the pleasure must be like bones dissolving, flesh melting. Why was I so strict and tight with him? Why had I moved to his shabby room in the first place?”

Ding Ling 60-1.

Here, Sophia finally has the chance to sit alone with the man she so desperately longs for sexually. She is being handed him on a silver platter, he initiates all conversation, and yet she pulls away and wants to make a fool of him. This is kind of the core of Sophia’s character. To most people, I can imagine her back-and-forth could seem a bit frustrating; but once you sit down and think about it for a while, isn’t it kind of relatable? For example, people will always say “Just ask them out, the worst they can say is ‘no’,” but most people will hear that and imagine so much worse happening than just a “no.” Sophia is the same way, she doesn’t want to jeopardize the character she has created for her public-facing self if she finally takes the step to be vulnerable. Sophia seems to take this approach with all of her relationships, even with the people who she is willing to get teary-eyed in front of.

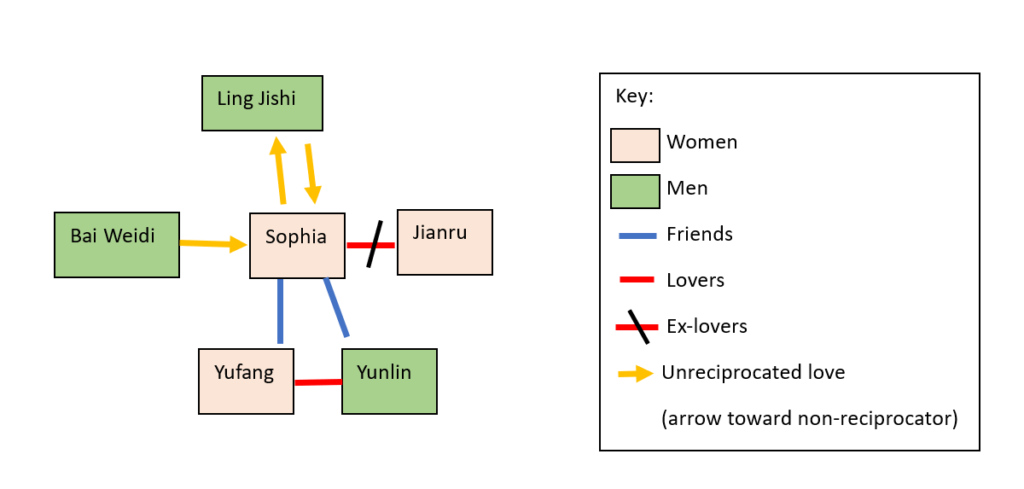

“Miss Sophia’s Diary” itself isn’t very long at all, but I will say it took me a fair amount of time to read— mostly since I had to keep track of lots of names that popped up at random. However, I did like that Sophia never really took the time to explain who these people were and just went on telling her story, because of course she wouldn’t, this is her diary, why would she need to recount who her friends are? Still, it made it a bit hard to keep track of people, so I ended up keeping a list of who was who and what their relationships were (if they were significant enough).

Going off of this idea of Sophia just sort of randomly introducing people and information, I was really struck by how casually she admits to being bisexual as a Chinese woman in the 1920s:

“December 28

In invited Yufang and Yunlin out to the movies today. Yufang asked Jianru along, which made me so furious I almost burst into tears. Instead I started laughing. Oh, Jianru, Jianru, how you’ve crushed my self-respect. She looks and acts so much like a girlfriend I had when I was younger, that without being aware of what I was doing, I started chasing her. Initially she encouraged by intimacies. But I met with intolerable treatment from her in the end. Whenever I think about it, I hate myself for what I did in the past, for my regrettably unscrupulous behavior. One week I wrote her at least eight long letters, maybe more, and she didn’t pay the slightest bit of attention to me. Whatever possess Yufang to invite Jianru when she knows I don’t want to dredge up my past all over again? It’s as though she wanted to make me mad on purpose. I was furious.”

Ding Ling 52-3

Reading this section gave me pause. I had to wonder, was she saying “girlfriend” to mean a girl that is her friend in the way that some people do now (a practice that I find quite annoying for this exact reason), or was she declaring that she used to have a girlfriend that reminded her of Jianru, giving Sophia a reason to want to date Jianru? The very prospect of this got me so very excited. A Chinese woman in the 1920s openly sharing her sexuality? Amazing! A woman writer who was extraordinarily influential in women’s writing in China being the one to write this moment? Even better! But that nagging feeling of there being a possibility that Sophia and Jianru were just friends made me hesitant to get fully excited about the idea. But honestly, I don’t think there’s any other way to interpret it, even if we look at the word “girlfriend,” Sophia isn’t referring to Jianru just yet, she’s saying “a girlfriend I had,” so this could mean just a friend or a lover; but either way, it led to her and Jianru to encourage each other’s “intimacies,” a phrase she does not use to describe her relationship with her other friends, so I quickly solidified the idea in my head. But just to be sure, I consulted my sister, someone who had read the story before and studied it; and although her full memories of the experience were fuzzy, she stated it was clear that this was more than a friendship.

So, once this idea was confirmed, I got to bask in the glory of it being so casual. Sophia’s sexuality and sexual exploration is a huge part of this story, but to her, this is just who she is and what she experienced, so it’s not a big deal. Therefore, it shouldn’t be a big deal to the readers either. I think there is something really special about this declaration being so nonchalant and “interpret-able” since Sophia clearly doesn’t need to spell out who she is for herself in her own diary—and we see her continue this pattern as she randomly mentions people once and never again with no explanation.

Moving away from the analysis of Sophia’s character and the way the story is relayed, I want to look specifically at the story’s plot. Although the piece is short, a lot happens on those pages. Ding Ling was able to cram countless events, with varying degrees of importance, and emotions onto each of her pages without ever having a single moment feel wasted or insignificant. I think her overwhelmingly strong creation of Sophia is what really drives me to believe this.

Although Ding Ling’s work, and this story specifically, are revered as important in the grand scheme of Chinese women’s literature, there isn’t a plot summary available for it anywhere. Most pages discussing it, including its Wikipedia entry, only deal with a basic overview and themes.

So, I have attempted to recount some of the more significant plot points—though I have left quite a bit out:

Miss Sophia’s Diary is the story of the titular character’s life, emotions, and relationships told via her dated diary entries. The story is told via the events of her daily life, and through those events, Sophia reveals information about her own character, her relationships, and her health. Sophia is suffering with tuberculosis, and is determined to live her life to its fullest.

The focus of the diary quickly becomes Sophia’s lustful obsession with a man from Singapore named Ling Jishi, who her friends Yunlin and Yufang introduced her to. Sophia ends up moving to a new apartment just for the opportunity to be closer to him, but she lies to Yunlin saying that the reason she wants to move is to be closer to Yufang. Sophia describes talking to Ling Jishi as “planning a battle” (58). She resolves that she will not be the one to make the first move as she does not want to seem weak.

After some time, Sophia’s condition worsens and she starts to drink in excess for the first time in six months. She begins to vomit and she describes what she throws up as “blood-redder than wine” (62). Sophia lays down sick in her bed, and her friends Yunlin, Yufang, Weidi (her friend who is in love with her), and Jinxia (appearing in her diary for the first time here) sit around her and weep over her condition. They then help Sophia gather some of her things and help her get to the hospital.

Sophia’s diary then jumps from the middle of January to the beginning of March, skipping over her hospital stay. She ends up back in her room, prepared for her by her friends. Yufang stays with Sophia during this time to take care of her, and she begins to help Sophia look for a new room to stay in at Western Hills so she can get out of Beijing and recover. During this time, Ling Jishi continues to grow closer to Sophia, but she still has not revealed her feelings.

After days of not writing, Sophia reflects on her emotions, specifically regarding Ling Jishi. She realizes that she is only attracted to his physical beauty because, as she learns more about him, she realizes that he has modest ambitions and wants to simply be a successful capitalist. However, in the next diary entry, she says that she can’t stop thinking about him. Ling Jishi then arrives at her home to make sure she is not upset with him. Sophia remarks that she is annoyed with how disconnected he is to her desires. She listens to him talk for a while, then once again, becomes upset as he leaves.

Yufang then tells Sophia that she found her a room in Western Hills with a friend who was also recovering from an illness. Sophia tries to be happy about this, but she is worried about being truly alone for the first time in her life. Sophia then waits for Ling Jishi to come over, as he promised he would return to her room that night when he discovered she was moving. The diary skips to the next day after Sophia notes that time ticks on from 9pm to 9:40, with still no sign of him.

In her final entry, Sophia says that she will no longer be writing because she no longer needs the diary. She says she doesn’t need it anymore because she has realized that nothing has any meaning. She reflects on how she behaved regarding Ling Jishi, she then admits that he came to room at 10pm the night prior, saying that he wanted her. She recounts that she thought his words were pathetic and that she was offended by the idea that he thought all she wanted was marriage, children, and status. Sophia laughed at his remarks, but Ling Jishi kissed her, and she describes herself as having “endured” it.

Sophia then ends her diary by admitting that she is not going to Western Hills, she is going on a train to get farther from Beijing than before.

After reading “Miss Sophia’s Diary,” I wondered how on earth this could be adapted in any way other than changing the setting or the genders of the people Sophia lusted over—changes that wouldn’t really affect the plot very much since the plot is a product of who the character is; and I feel as if Sophia is a very anachronistic character, she can be set anywhere and still be Sophia. I see parts of myself in Sophia and she was created with the image of a far different place and time influencing her in mind. Nevertheless, I find her and her struggles relatable and applicable to today.

Despite my confusion about how to adapt the story, I settled on the idea that it would be interesting to play up the idea of Sophia’s bisexuality. Thus, I wanted to make Ling Jishi a woman in this version to show off her bisexuality more explicitly.

Miss Sophia’s Diary is the story of the titular character’s life, emotions, and relationships told via her dated diary entries. The story is told via the events of her daily life, and through those events, Sophia reveals information about her own character, her relationships, and her health. Sophia is suffering with tuberculosis, and is determined to live her life to its fullest.

The focus of the diary quickly becomes Sophia’s lustful obsession with a woman from Singapore named Ling Jishi, who her friends Yunlin and Yufang introduced her to. Sophia ends up moving to a new apartment just for the opportunity to be closer to her, but she lies to Yunlin saying that the reason she wants to move is to be closer to Yufang. Sophia describes talking to Ling Jishi as “planning a battle” (58). She resolves that she will not be the one to make the first move as she does not want to seem weak.

After some time, Sophia’s condition worsens and she starts to drink in excess for the first time in six months. She begins to vomit and she describes what she throws up as “blood-redder than wine” (62). Sophia lays down sick in her bed, and her friends Yunlin, Yufang, Weidi (her childhood friend who is unabashedly in love with her), and Jinxia (appearing in her diary for the first time here) sit around her and weep over her condition. They then help Sophia gather some of her things and help her get to the hospital.

Sophia’s diary then jumps from the middle of January to the beginning of March, skipping over her hospital stay. She ends up back in her room, prepared for her by her friends. Yufang tries to stay with Sophia during this time to take care of her, but Weidi forces himself into the position, and so Yufang leaves and begins to help Sophia look for a new room to stay in at Western Hills so she can get out of Beijing and recover. During this time, Ling Jishi continues to grow closer to Sophia, coming only to talk to her when Weidi is gone, but Sophia still has not revealed her feelings.

After days of not writing, Sophia reflects on her emotions, specifically regarding Ling Jishi. She realizes that she is only attracted to her physical beauty because as she learns more about her, she realizes that she has modest ambitions and wants to marry a man, and never admit her sexuality so she can become a successful government official. However, in the next diary entry, Sophia says that she can’t stop thinking about Ling Jishi. Ling Jishi then arrives at her home to make sure she is not upset with her. Sophia remarks that she is annoyed with how disconnected she is to her desires, she thinks Ling Jishi’s desire to take the public service exam is nothing more than an excuse to avoid her feelings toward women. Sophia listens to Ling Jishi talk for a while, then once again, becomes upset as she leaves.

Yufang then tells Sophia that she found her a room in Western Hills with a friend who was also recovering from an illness. Sophia tries to be happy about this, but she is worried about being truly alone for the first time in her life. Sophia then waits for Ling Jishi to come over, as she promised she would return to her room that night when she discovered she was moving. The diary skips to the next day after Sophia notes that time ticks on from 9pm to 9:40, with still no sign of her.

In her final entry, Sophia says that she will no longer be writing because she no longer needs the diary. She says she doesn’t need it anymore because she has realized that nothing has any meaning. She reflects on how she behaved regarding Ling Jishi, she then admits that Ling Jishi arrived to her room at 10pm the night prior, saying that she wanted her. She reflects on how she thought that Ling Jishi’s words were pathetic, especially after Ling Jishi confided that she would never want to come out, as Ling Jishi talks to her about marriage, children, and hiding their relationship behind false relationships with men so they could both retain the status of valued Chinese government officials. Sophia laughed at her remarks, but Ling Jishi kissed her, and she describes herself as having “endured” it.

Sophia then ends her diary by admitting that she is not going to Western Hills, she is going on a train to get farther from Beijing than before.

The changes are minor, but I think that the shift from making Ling Jishi just a capitalist to someone who wants to work in Chinese government makes the story slightly more modern as that’s not a Maoist idea, rather a Deng idea, since he was the one to turn China into a meritocracy. Moreover, making Ling Jishi a woman added more focus to Sophia’s bisexuality, which was really important to me. The detail about it wasn’t significant enough to put in the plot summary itself, so I needed to find a way to better show it off.

The idea of unapologetically showcasing not only a woman’s sexuality, but her bisexuality in 1920s China seems to be a significant part of the story that gets overshadowed by the other aspects of the novel that made it important to Chinese history. So I wanted to show that sexuality off more by making the wlw (women loving women) side of her bisexuality at the forefront of the story alongside her more heterosexual side, as opposed to her wlw side simply being a footnote of an idea in this plot summary.

Work Cited

Ling, Ding, and Tani E Barlow. “Miss Sophia’s Diary.” I Myself Am a Woman: Selected Writings of Ding Ling, Beacon Press, Boston, MA, 1989, pp. 49–81.

Featured Image Attribution

“Ding Ling” by plumsaplomb is marked with Public Domain Mark 1.0.