For our first assignment, I asked you all to explore how narrators shape your favorite literary works. Though I didn’t explain it in this way at the time, we were beginning the process of reverse engineering literature. This is a process Angus Fletcher models in Wonderworks, and it’s a method that originated with Aristotle’s Poetics (written over two thousand years ago). The Poetics provide what Fletcher describes as an invention-finding method. In the introduction to Wonderworks, he explains the “essential action” of Aristotle’s “invention-finding method”:

First, identify what literature does, and second, work backward to uncover how literature does it. The what is the specific psychological effect of a literary work; an effect that’s typically linked to emotion. The how is the unique literary invention that drives the effect; an invention that’s usually engineered from one of the core elements of narrative: plot, character, storyworld, and narrators.

Introduction to Wonderworks

I’ve decided to organize the four units of our course into these four core elements of narrative. I’ll review them quickly, just so you have a sense of what is to come.

Narrator

We jumped right into this element with our first assignment. I introduced a few techniques of narration (there are many more than what I introduced!!). For the first assignment, I asked each of you to explore how your favorite literary works are narrated to help isolate what made your chosen work impactful for you. Some of you discovered, however, that the distinctive feature of your favorite work wasn’t so much about the narrator, but about one of the other core elements of narrative.

Plot

The plot is what actually happens in the story, though the narrator may present it out of order, through a variety of perspectives, or in some other non-linear telling. The first step of understanding how literature works, I think, is to separate the story from its telling. Almost every Wikipedia article about a work of literature has a section with the heading of “Plot Summary.” As we’ve discussed, reading a plot summary can never come close to the experience of actually reading, watching or playing because it is meant only to convey a summary of the plot. I never thought to look into this before, but I just looked at the guidance Wikipedia editors have written on the creation of plot summaries and was delighted to find that they clarify the distinction there. The project page, Wikipedia: How to write a plot summary, explains “The objective point of a plot summary is to condense a large amount of information into a short, accessible format. It is not to reproduce the experience of reading or watching the story, nor to cover every detail.” If the process of separating the plot from the other elements of a literary work is interesting to you, I encourage you to check out the full project page. My plan when we tackle plot for the third assignment is to encourage you all to think about what events get included and what events get left out of the works you’re reading at that time. To me, the obscenity trials that impacted Modernist authors are an issue of plot. Literary works like Joyce’s Ulysses include events that had, to that point, been considered taboo.

Character

This is pretty straightforward. Characters are typically referred to by narrative theorists as “actors.” If the literary work is a play, they are typically introduced at the start of the play in a dramatis personae. When we delve into character for the fourth assignment, I’ll be inviting you all to think about how characters are created by writers. Often characters are built with reference to other characters who have come before. I think this will allow us to talk about allusion and intertextuality. We’ll get to that, all in good time. But for now we’ll focus on…

Storyworld (The element we’re focusing on for assignment 2!)

You might understand storyworld as the setting of a literary work, but it’s really more than that. This is because you (the reader, viewer, or player) actually create the storyworld in your mind as you read, watch, or play. As Marie-Laure Ryan explains in her book Storyworlds Across Media : Toward a Media-Conscious Narratology, “a storyworld is more than a static container for the objects mentioned in the story; it is a dynamic model of evolving situation, and its representation in the recipient’s mind is a simulation of the changes that are caused by the events of the plot” (33). Ryan is a narrative theorist and her book contains the detailed terminology that is typical of the field (though not necessary to understand the basics of what a storyworld is). Nevertheless, I’ve provided a link to the chapter I’ve referenced in this post in the Works Cited list if you want to give it a look.

Even in a film, you imagine yourself to be in a world that is consistent with what the camera is showing you, though the film only shows you parts of that world; you imagine that the rest of it exists.

Humans do this work imagining a full story world automatically when we truly engage with a work of fiction. We imagine the full world of the story even beyond what is shared about it by the narrator. When I first read the opening lines of Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale, narrated in the first person by Offred, I was prompted to begin constructing a storyworld that used to be like the world I live in. Offred, the narrator, describes events that no longer occur:

We slept in what had once been the gymnasium. The floor was of varnished wood, with stripes and circles painted on it, for the games that were formerly played there; the hoops for the basketball nets were still in place, though the nets were gone. A balcony ran around the room, for the spectators, and I thought I could smell, faintly like an afterimage, the pungent scent of sweat, shot through with the sweet taint of chewing gum and perfume from the watching girls, felt-skirted as I knew from pictures, later in mini-skirts, then pants, then in one earring, spiky green-streaked hair. Dances would have been held there; the music lingered, a palimpsest of unheard sound, style upon style, an undercurrent of drums, a forlorn wail, garlands made of tissue-paper flowers, cardboard devils, a revolving ball of mirrors, powdering the dancers with a snow of light.

There was old sex in the room and loneliness, and expectation, of something without a shape or name. I remember that yearning, for something that was always about to happen and was never the same as the hands that were on us there and then, in the small of the back, or out back, in the parking lot, or in the television room with the sound turned down and only the pictures flickering over lifting flesh.

The Handmaid’s Tale, Chapter 1

She’s describing a memory of school basketball games and dances, complete with groping (“hands that were on us there and then”) and disco balls (“revolving ball of mirrors, powdering the dancers with a snow of light”)–things that don’t happen in the gymnasium anymore. And as she remembers those things, she also remembers, “we used to yearn for the future” (They don’t yearn for the future anymore? What happened to change things?):

We yearned for the future. How did we learn it, that talent for insatiability? It was in the air; and it was still in the air, an afterthought, as we tried to sleep, in the army cots that had been set up in rows, with spaces between so we could not talk. We had flannelette sheets, like children’s, and army-issue blankets, old ones that still said U.S. We folded our clothes neatly and laid them on the stools at the ends of the beds. The lights were turned down but not out. Aunt Sara and Aunt Elizabeth patrolled; they had electric cattle prods slung on thongs from their leather belts.

Handmaid’s Tale, Chapter 1

Instead of yearning for the future, they now try to sleep. This group of people laying on army cots in something that used to be a gymnasium is using army-issue blankets that “still said U.S.” (does the United States no longer exist?). And now there are two Aunts on patrol, with cattle prods on leather belts. (What is happening here?)

These are the things I thought as I read The Handmaid’s Tale for the first time. And gradually, as I read more of Offred’s narration, it became clearer and clearer to me that this was a dystopian world. I learned the rules of this world as Offred explained her experience of them. But soon I was imagining what was happening elsewhere in the storyworld, even if Offred didn’t specifically narrate it. I imagined other handmaids in other houses in a society that was different from the one I lived in. This is the brilliance of the technology of story. As we experience a story, our brains begin to extrapolate the implications of the world of that story (perhaps without even consciously trying to do so).

This is somewhat easy to explain when the storyworld is fictional and also different from our own experiences. But Marie-Laure Ryan explains that we imagine a storyworld even when experiencing nonfiction:

If we conceive of the real world as a domain made of facts that exist independently of the mind and of any attempt to narrate them–as a domain, in other words, whose description is a collection of true propositions–then associating the story world of a story with the real world makes this story automatically true. Nonfictional stories are told as true of the real world, but they do not necessarily live up to this idea. The storyteller can be lying, misinformed, or playing loosely with the facts. It is therefore necessary to distinguish the world as it is presented and shaped by a story from the world as it exists autonomously.

Marie-Laure Ryan 33

Even a work of nonfiction creates a storyworld. We decide how true that story is as we compare it back to the world we know. As Ryan puts it, “assessing the truth of a story means assessing to what extent the storyworld corresponds to the reference world” (33). By “reference world,” she means the “real world” that we actually live in. If my son tells me a tragic story about his brother throwing goldfish all over the kitchen floor, he has created a storyworld. I could assess the truthfulness of that story by referring to surveillance footage of my kitchen. I might do this if I had surveillance cameras in my kitchen, which I do not (thankfully), so ultimately I can’t know for certain if the story is true or not (though I can make a pretty good guess depending on how much his brother protests).

Okay, so we’ve established what a storyworld is (I hope). We can certainly talk more in class about what it is and how it works. Please bring your questions.

Thinking about the role of storyworld in our experience of literary works can be very revealing. It’s raised many questions for me that I’ll share here, and I encourage you to develop your own questions about storyworld in the texts you’re reading/watching/playing.

Storyworlds Set in the Past

Conversations with all of you last week have helped me think about storyworld in relation to the novel that I started re-reading after writing my last post: George Eliot’s Middlemarch.

A number of you are interested in reading some of the nineteenth-century authors one might expect to appear on a British literature reading list. I think that because there’s no expectation that you finish anything you start reading or appreciate authors in any particular way, I’m getting much more honest responses about your reading experiences. And here’s what I’m learning. Some of you genuinely want to read Austen or Brontë or Eliot or Dickens but when you actually do try to read their work, you find the sentence structure and vocabulary too unfamiliar to be enjoyable. This is understandable! It’s a much less fun experience if you have to take the time to look things up to make sense of what you’re reading. I remember buying my best friend a copy of Middlemarch and sending it to her as a gift (we were both in our early twenties) and she told me later, “Um, yeah. I stopped after the first chapter. What do you like about that novel?!” I didn’t really have an answer for her at the time.

So, why do I enjoy these novels? I think it’s because I love inhabiting the storyworld created by an author who actually lived in that period. There is some fantastic historical fiction out there, written now but set in the past (check out The French Lieutenant’s Woman if this is something that interests you) but I’m talking about nineteenth-century novels written in the nineteenth century. I think it’s easier for me to inhabit those storyworlds because I love all things olden. I spent many years working on a dissertation about the nineteenth century, which involved reading many novels and plays, but also many letters, diary entries, and newspaper stories written in the period. All of this research immersed me in that earlier historical period and made it easier and more enjoyable for me to experience the storyworlds created by authors living at that time. I understand vocabulary and historical context in these novels and that makes it easier to enjoy them. This helps me understand why I have such a hard time enjoying certain others genres that my students have recommended to me. I just can’t picture the storyworld. I don’t “get it.” Now, if I really wanted to get it, I could just start immersing myself in the details of those worlds so it would become easier. But there’s only so many hours in the day.

Just to be clear, I’m not sitting down and holding a print copy of Middlemarch. I’m listening to a free recording of it as I commute to work. If any of you want to experiment with this, just copy the RSS feed from any Librivox title and enter that text into the search field on your favorite podcasting app. That should allow you to subscribe to the entire work, as though it were a podcast.

You’re welcome.

So, I think I’ve figured out what has enabled me to get into these storyworlds, but I’m also trying to figure out why I enjoy being immersed in these storyworlds each time I read. This is the thing that makes reading a pleasure instead of work. I think in part it’s about inhabiting a storyworld that does not include most of the technologies that we take for granted today. Because I’m unable to extricate myself from the overwhelming technologies that make up my day (e-mail, text messages, social media, television, Canvas, etc.), I like inhabiting a world where you literally had to sit down and write a letter if you wanted to say something to someone who didn’t live at your house. And it was going to take days for a horse to carry you to another city, or months at sea to get across the ocean. I think inhabiting that world feels like a break.

I’m also happy to report that if I happen to be stuck in traffic and someone is reading the novel to me, I still enjoy the experience. I felt real emotion (empathy) as I drove down Whalley Avenue, listening to the narrator explain how Dorothea, aged 19, went about writing a letter to accept the offer of marriage from a man in his late forties.

After dinner, when Celia was playing an “air, with variations,” a small kind of tinkling which symbolized the aesthetic part of the young ladies’ education, Dorothea went up to her room to answer Mr Casaubon’s letter. Why should she defer the answer? She wrote it over three times, not because she wished to change the wording, but because her hand was unusually uncertain, and she could not bear that Mr Casaubon should think her handwriting bad and illegible. She piqued herself on writing a hand in which each letter was distinguishable without any large range of conjecture, and she meant to make much use of this accomplishment, to save Mr Casaubon’s eyes. Three times she wrote.

MY DEAR MR CASAUBON, – I am very grateful to you for loving me, and thinking me worthy to be your wife. I can look forward to no better happiness than that which would be one with yours. If I said more, it would only be the same thing written out at greater length, for I cannot now dwell on any other thought than that I may be through life, yours devotedly,

DOROTHEA BROOKE.

Middlemarch, Chapter 5

Part of appreciating this moment in the novel involves understanding that we’re in a storyworld in which women are not educated in the same way as men. Some women, like Dorothea’s sister Celia, don’t mind this. Some women, Like Dorothea, really do feel the restriction it places on her. Dorothea thinks she is liberating herself from expectations of what a young woman ought to care about by pursuing a life of the mind, but she’s doing this by entering a different sort of constraint. All of this is part of the storyworld that is different from the world we live in now (but would have been familiar to Eliot’s nineteenth-century readers). Another part of what I appreciate about this moment is conveyed through the narration, which hints that Dorothea is hiding feelings from herself. She is very certain in her mind that she wants to marry Casaubon (everyone around her warning her its a bad idea only makes her more sure), but perhaps there’s a part of her she can’t even fully access that realizes she’s making a mistake. Her hand is trembling so she writes the same thing out three times. Here, I appreciate the subtle suggestion of uncertainty when the narration of her behavior (her hand was unusually uncertain) is contrasted with the narration of her thoughts (why should she defer the answer?).

Science Fiction Storyworlds

I’ll move quickly through the other interesting examples of storyworld since this post is getting long! I wanted to tell you about Ursula K. LeGuin’s brilliant novel The Left Hand of Darkness. LeGuin wrote a fantastic Introduction to the novel after it was first published in which she describes how she uses the storyworld to explore a thought experiment: “if warfare is predominantly a male behavior, and if people are either male or female for only a few days a month during which their sexual drive is overwhelmingly strong, will they make war?” (LeGuin).

Absurd Storyworlds

I also want to introduce you to writers who create absurd storyworlds in which absurd or unreasonable behavior (to us) is not acknowledged as such. Harold Pinter is a British dramatist whose characters often behave in this way. One of his plays, The Homecoming, was made into a film that is helpfully available on YouTube. It’s delightfully weird. I think the absurdity gives everything they say much more significance. The whole scene lasts about ten minutes. I view the conversation between the two characters as more of a power play than anything else. When I first watched it, I thought “Why are they talking to each other in this way? What is actually going on?” I think the female character in the scene I’ve cued up below steals the power from the man in the burgundy robe because instead of acknowledging his absurd hostility with shock or disapproval, she responds in kind.

I think about this scene often, especially when trying to make sense of the way all of Wes Anderson’s characters behave. What are we to make of this monotone delivery of shocking information? How does it impact us as viewers?

Storyworlds that Draw Attention to their Fictionality

I also encourage you to explore the wonderful world of metafiction and metatheater, which I think also relates to storyworld. Marie-Laure Ryan explains that storyworld also helps us think about what is happening when literary works are drawing attention to their own fictionality. She begins by explaining that in many novels, the narrator doesn’t have an identity. It just conveys the story.

Just as the narration and the narrator may not exist in the world of novels, the camera that records the action does not exist in the story world of fiction films unless they thematize the process of their own production. Spectators do not imagine that they are watching a camera recording of certain events; instead, they pretend that they are watching unmediated events. (In a documentary film, by contrast, the spectator remains aware that a camera situated on the scene captured the images; this knowledge is what gives the film its documentary value.) Since the camera does not exist in the story world of fiction film, neither do all the effects of camera movement and editing.

Marie-Laure Ryan 38

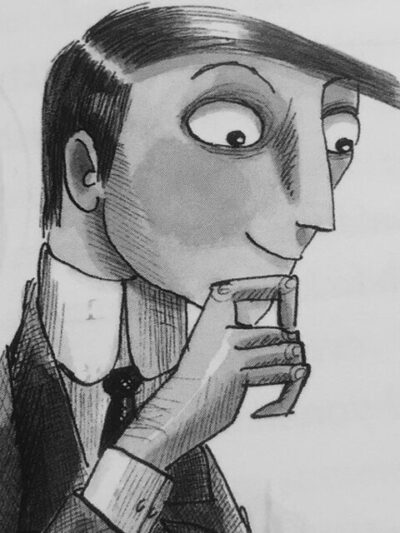

Some of my favorite literary works involve metafictional and metatheatrical moments in which characters “break the fourth wall,” reminding readers and viewers that the story is fiction. This is especially common in “story within a story” shows like 30 Rock.

I’m still trying to work out what I want to say about the fact that Fleabag regularly looks at the camera in that show. While this happens through the entire first season and none of the other characters ever notice what she’s doing (even when she turns away from them mid-sentence), there is one character in the second season who notices what she is doing.

IF YOU’RE GOING TO WATCH FLEABAG, DON’T WATCH THIS MONTAGE

Can Storyworlds Shape our Perspective on Reality?

In the world of crime fiction, some stories unfold in a storyworld where the police are corrupt. Other stories unfold in a storyworld where police officers are good. Though he doesn’t present it in exactly this way, I see Malcolm Gladwell’s episode of Revisionist History (embedded below) as addressing the impact of these storyworlds on the way we all view police officers in the real world. He opens the episode (actually a recorded lecture from the New Orleans Book Festival) by describing the massive amount of crime fiction that has been produced in America. He begins by stating that our attitude toward the police in the United States is really weird. He points out that there are two million truck drivers in America, but there’s not a genre of trucker fiction. There are three million nurses in America, but there’s not a genre of nurse fiction. There are four million teachers in America, but there’s not a genre of teacher fiction. There are 700,000 police officers and they are massively overrepresented in fiction in our country. He then states his question: “What have we learned from our immersion in all of these police procedurals and crime novels and what are the social consequences of that learning, which is an important question because I think all those crime books and movies have really really screwed us up” (8:42).

He might not have specifically used the term “storyworld,” but he’s clearly talking about storyworld!

I think another version of this question applies to science fiction and our beliefs about artificial intelligence in the real world. Regular people are increasingly able to interact with large language models (like chatGPT). Science fiction has given us MANY storyworlds in which computers and robots become sentient. People who are regularly immersed in these storyworlds have slightly different perspectives on what is actual possible (and desirable) in the real world. Jill Lepore tackles this issue in the second episode of her podcast Elon Musk: The Evening Rocket. Introducing the episode, she explains that the futurism currently driving Silicon Valley emerges from the science fiction that Elon Musk grew up reading (3:14).

Works Cited

Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. 1st Anchor Books edition, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 1998.

Eliot, George. Middlemarch. 1891. Internet Archive, http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.42254.

Fletcher, Angus. “Introduction.” Wonderworks: The 25 Most Powerful Inventions in the History of Literature, First Edition, Simon & Schuster, 2021.

Gladwell, Malcolm. Taxonomy of the Modern Mystery Story | Revisionist History. https://www.pushkin.fm/podcasts/revisionist-history/taxonomy-of-the-modern-mystery-story. Accessed 9 Feb. 2024.

Lepore, Jill. The Evening Rocket: Baby X | Elon Musk: The Evening Rocket. https://www.pushkin.fm/podcasts/elon-musk-the-evening-rocket/the-evening-rocket-baby-x. Accessed 9 Feb. 2024.

Ryan, Marie-Laure. “Story/Worlds/Media Tuning the Instruments of a Media-Conscious Narratology.” Storyworlds Across Media : Toward a Media-Conscious Narratology, University of Nebraska Press, 2014.

“Wikipedia:How to Write a Plot Summary.” Wikipedia, 15 Dec. 2023. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Wikipedia:How_to_write_a_plot_summary&oldid=1190097082.

Featured Image

Still from Fleabag by Phoebe Waller-Bridge. Produced by Two Brothers Pictures. All Rights Reserved.