What was the Stonewall Uprising?

The Stonewall Uprising, also called the Stonewall Riots, or simply Stonewall was a turning point for LGBTQ rights in the United States. On the late night of June 27th, 1969, or in the very early morning of June 28th, 1969, Police raided a well-known gay bar in the heart of Greenwich Village: The Stonewall Inn. At this time, police raids on gay bars were incredibly common. These raids would typically be violent and result in police brutality against the LGBTQ bar patrons. As typical as this was, the patrons usually did not fight back. Until this night in particular. As the police attempted to arrest individuals and shut down the bar, the crowd inside and supporters from outside began to throw bottles and other debris at the officers. The uprising lasted on and off for several days, until July 3rd. Stonewall is considered the spark behind the LGBTQ movement in the United States. The Stonewall Uprising was not a singular event but more so a series of demonstrations and defiant acts. The anger and frustration expressed at Stonewall were not isolated to New York City but reflected countrywide and worldwide struggles against discrimination, and injustice faced by the LGBTQ community.

“[Stonewall was] the shot heard round the world…crucial because it sounded the rally for the movement.” – Lillian Faderman, historian

The Stonewall National Monument

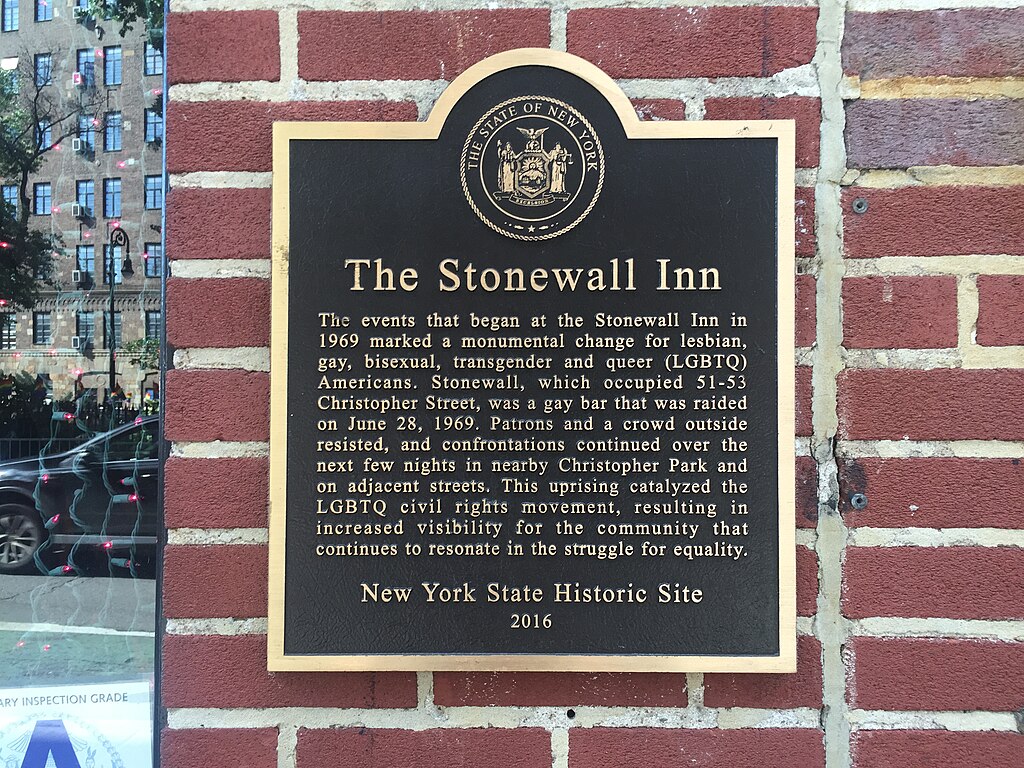

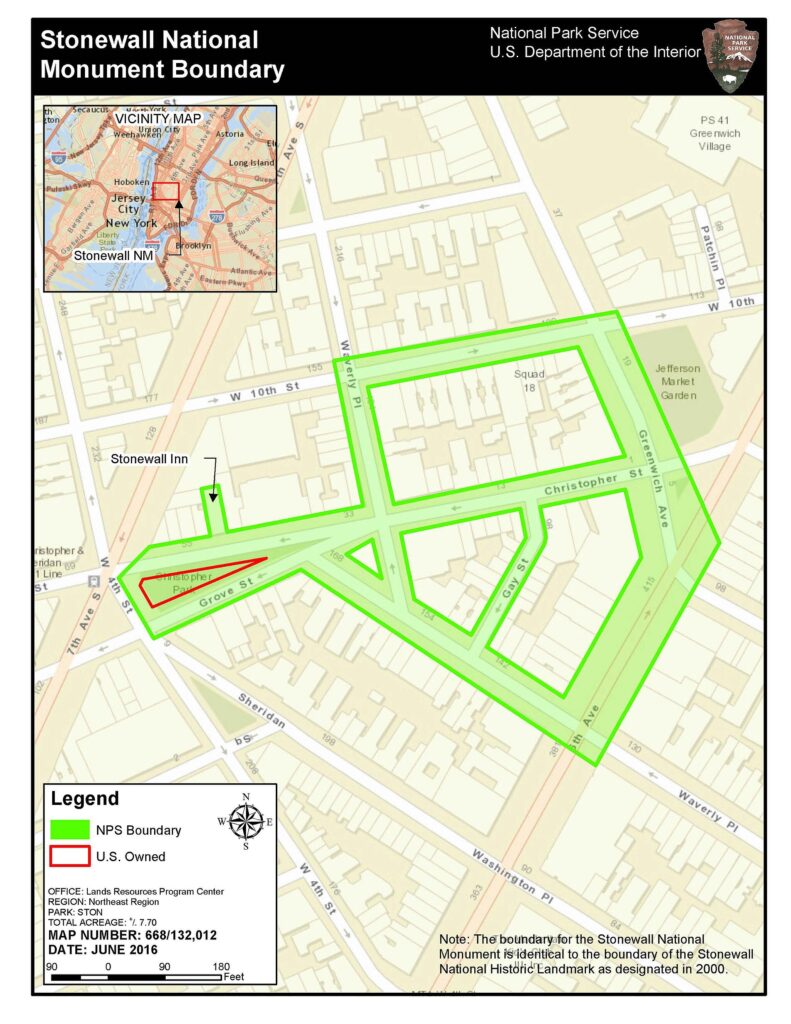

Stonewall was first listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1999. Then in 2000 it was named a named a National Historic Landmark. In 2015 it was declared a New York City Landmark and in 2016 it became a State Historic Site. On June 24, 2016, President Obama officially designated the 7.7-acre area surrounding Christopher Park, which was across the way from the Stonewall Inn, as the Stonewall National Monument.

“I’m designating the Stonewall National Monument as the newest addition to America’s National Park System. Stonewall will be our first national monument to tell the story of the struggle for LGBT rights. I believe our national parks should reflect the full story of our country, the richness and diversity and uniquely American spirit that has always defined us. That we are stronger together. That out of many, we are one.” – President Obama

The area encompassed in the monument includes the Stonewall Inn itself, as well as Christopher Park, which houses the Gay Liberation monument. The impact of the stonewall uprising goes beyond a singular event, as the monument is not just a simple statue, plaque or building. The expanse of the monument represents how the Stonewall riot moved beyond a mere event and instead led to broader social impact.

The Gay Liberation Monument

A decade after the Stonewall uprising, the Gay Liberation Monument was commissioned by arts patron Peter Putnam and built by George Segal. The monument is a part of the Stonewall National Monument that is in Christopher Park. It is a somewhat more traditional monument, in the sense that it depicts real human figures, and is made of bronze and steel. But somewhat more modern as they were painted white, as per Segal’s signature artistic style. The monument shows two men standing together and two women seated next to each other on a bench. Segal depicted them in causal relaxed poses; to demonstrate the comfortability the LGBTQ rights movement had brought to people. This monument was surrounded by controversy, mostly from the LGBTQ community itself. Segal’s statues were created and supposed to be unveiled in 1980 but were not until over a decade later due to controversy from Village residents, and the queer community.

The statues still remain a target of controversy, for many of the same reasons that prevented it from being installed. Of course, there are those that are simply homophobic and do not want there to be a monument to LGBTQ rights, but that is to be expected. However, Activists, who are the monument’s greatest critics, feel that the sculpture is not representative of the events of Stonewall. They feel that it makes no acknowledgment to the violence that occurred. Furthermore, many feel that the statues whitewash the event. Stonewall, and the early LGBTQ rights movement in New York City, was led by transgender women of color. Most notably were Marsha P Johnson, Miss Majors and Sylvia Rivera. Despite this, the monument is painted completely white, and the figures have European features. The statues do not lend any specific recognition to the black and brown gender nonconforming activists that led the movement.

In 2015, the statues were vandalized by two unknown queer women. They painted the hands and faces of the figures black and brown, and added wigs, bras and other accessories. They also left a sign that said

“Black Latina trans women led the riots, stop the whitewashing.”

They did not consider their acts vandalism and instead said they were rectifying the monument to honor its true history. The statues have since been repainted back to all white, despite a call for otherwise.

Why is this Monument Significant?

Despite some of the controversy the Stonewall National Monument was a crucial representation of LGBTQ history. The Stonewall National Monument was the first LGBTQ historical monument dedicated in the United States. The Stonewall National Monument goes beyond a monument, it is a place of gathering and refuge for the queer community. Christopher Park served as a haven for the LGBTQ community. Especially for unhoused youth. It remains an important place for the queer community. When the Supreme Court ruled that all states must recognize same-sex marriage in Obergefell v. Hodges, the queer community flocked to Christopher Park to celebrate the momentous occasion. When 49 members of the LGBTQ community were gunned down at the Pulse nightclub in early June of 2016, supporters again were drawn to Christopher Park, to mourn the lives lost in the tragic hate crime. Both of these events were before the location was even designated as a monument. It didn’t need the designation to be deeply important to the community.

While the criticisms of the monument are valid, the importance of The Stonewall National Monument transcends them. The monument may not fully capture the struggle the LGBTQ community faced at the Stonewall Inn on that fateful night, or the pivotal people in the riots. However, its very existence is a step in the right direction. As the first queer history monument in the United States, it is a physical reminder that the queer community has always existed and always fought and will continue to do so. Because of the controversy, more light has been shed on the major contributions made by transgender women of color, and how the uprising may not have happened without them, and now their memory and impact is starting to be properly recognized. Overall, the monument’s existence demonstrates the capacity for change and allows for conversations to continue. Criticism and conflict are what allow for change.

Sources:

Armstrong, E. A., & Crage, S. M. (2006). Movements and Memory: The Making of the Stonewall Myth. American Sociological Review, 71(5), 724–751. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25472425

Browning, B. (2021, July 23). Activists vandalize New York City stonewall monument to protest “whitewashing.” Advocate.com. https://www.advocate.com/stonewall/2015/08/19/activists-vandalize-new-york-city-stonewall-monument-protest-whitewashing

Christopher Park Monuments – Gay Liberation : NYC parks. Official Website of the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. (n.d.). https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/christopher-park/monuments/575

Communications, N. W. (n.d.). Gay Liberation Monument. NYU. https://www.nyu.edu/life/arts-culture-and-entertainment/galleries/galleries-and-sites/Gay-Liberation-Monument.html

Leiro, S. (2016, June 24). President Obama Designates Stonewall National Monument. Retrieved November 16, 2024, from https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2016/06/24/president-obama-designates-stonewall-national-monument

Michaeli, S., & Leonard, T. (n.d.). Stonewall · National Parks Conservation Association. National Parks Conservation Association. Retrieved November 19, 2024, from https://www.npca.org/parks/stonewall-national-monument

Mumford, K. (2019). The Lessons of Stonewall Fifty Years Later. QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking, 6(2), 85–90. https://doi.org/10.14321/qed.6.2.0085

Presidential Proclamation — Establishment of the Stonewall National Monument. (2016, June 24). Obama White House. Retrieved November 19, 2024, from https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/06/24/presidential-proclamation-establishment-stonewall-national-monument

Research Guides: LGBTQIA+ Studies: A Resource Guide: 1969: The Stonewall Uprising. (n.d.). Library of Congress Research Guides. Retrieved November 19, 2024, from https://guides.loc.gov/lgbtq-studies/stonewall-era Stonewall Inn – NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project. (n.d.). NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project. Retrieved November 19, 2024, from https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/stonewall-inn-christopher-park/