On a small grassy hill in Montana sits a large granite obelisk, etched with the names of over 260 soldiers1 who fell in one of the most iconic and controversial battles in American history. The Seventh Cavalry Memorial, sitting atop Last Stand Hill and marking the location of the Battle of Little Bighorn, is more than a marker of graves but a symbol of how America decided to remember the bloody outcome of their efforts to manifest destiny.

Background

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, fought on June 25 and 26, 18762, was a pivotal event in the U.S.’s westward expansion efforts. In 1868, the United States offered the Native Americans the Treaty of Fort Laramie, which promised that their land, including the Black Hills, would be guaranteed to them. When gold was discovered on the Black Hills shortly after, the United States broke the treaty and attempted to negotiate their ownership of the Black Hills. The Lakota declined this deal, and in turn, the United States declared the Lakota hostile and engaged military action against them3.

Led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, the U.S. Army’s Seventh Cavalry was tasked with engaging the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes. Custer had attended West Point, where he graduated last in his class4, but he quickly became a Union Civil War hero known for his aggressive tactics5. During the Battle of Little Bighorn though, Custer strongly underestimated the strength and coordination of the Native forces. Dividing up his 600 men, he launched a poorly planned attack on a huge encampment of Native warriors. The Seventh Cavalry was overwhelmed. Custer and his men were defeated and killed, with most of his men perishing on Last Stand Hill. This battle was a significant victory for the Native Americans, but prompted even more military response from the U.S. Within a year, most resisting tribes had surrendered6.

The Monument

“Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument” by the National Parks Gallery is licensed under Public Domain.

After their death, the members of the Seventh Cavalry were buried where they fell in shallow graves7. In 1879, the Secretary of War first preserved the site as a U.S. National Cemetery to protect graves of the Seventh Cavalry troops buried there. Many of the officers’ bodies were moved to various locations around the nation, and Custer’s body was moved to West Point in 1877. As for the other soldiers, their bodies were moved to form a mass grave near the Seventh Cavalry monument built in July of 1881.8 This memorial was built by Lieutenant Charles F. Roe and the 2nd Cavalry9 and still stands today on the top of Last Stand Hill.

In the 1880s, the U.S. was making significant progress in gaining control of the West. Building monuments like the Seventh Cavalry memorial allowed the U.S. to ultimately justify their actions against the Natives. By honoring prominent figures like General Custer, the U.S. portrayed a one sided story of westward expansion, painting the military as heroic and honorable. It is uncommon to create a memorial to the loser of a battle, but doing so furthered the idea that the Native Americans were savages and the U.S. military was justified in their actions. This was significant in defining national identity, shaping public memory, and reinforcing the legitimacy of the continued assault against the Native Americans.

The Seventh Cavalry Monument itself stands approximately 11 feet tall, and is inscribed with the names of the fallen. It stands at the top of Last Stand Hill, giving it more height. It conveys heroism, solemnity, and strength, towering over visitors. The granite is white, conveying innocence and purity, and was a common material at the time. The graves around the base of the monument add to the feeling of solemnity. The inscription reads as follows:

In memory of

Officers and soldiers who fell near this place

fighting with the 7th United States Cavalry

against the Sioux Indians

on the 25th and 26th of June,

A.D. 187610

The inscription is mostly unbiased, but ignores the context of the battle. This inscription, paired with the other characteristics of the memorial subtly convey the message that these soldiers died for a noble cause, pushing the one sided story of heroism. What furthers this interpretation the most though is that at the time, only the U.S.’s perspective of the war was memorialized. The Native American warriors who fought and died defending their land were not acknowledged, their side of the story left out entirely. This lack of representation shaped how the public understood the event for generations.

Public Perception

Back Then

When the Seventh Cavalry Memorial was erected in 1881, it was largely embraced by the American public. It symbolized mourning for the Seventh Cavalry, and justified the U.S.’s broader goal of westward expansion. It aligned closely with the existing ideals of the period, and the dream of manifesting destiny – the idea that American expansion across the continent was both justified and inevitable. Shortly after the battle, The Times newspaper published an article about the battle with the headline “Massacre of our Troops”, and labeled the Native Americans who fought “an overwhelmingly large camp of savages”11.

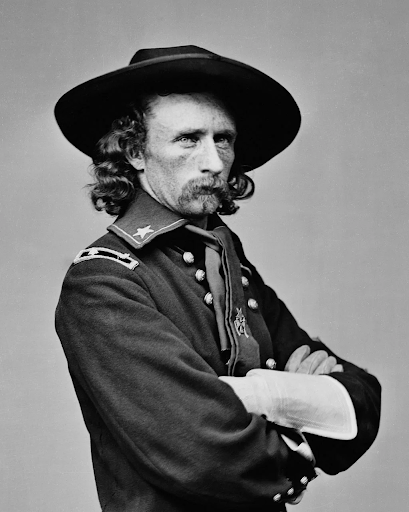

General Custer himself was also a well liked figure during his lifetime. His role in the Civil War allowed him to rise to fame, and his role as General of the Seventh Cavalry only added to his reputation. He was often referred to as an “Indian fighter,”12 a term used positively at the time. After his death, Custer continued to be well liked by the American public, being labeled as a great American warrior. Custer’s wife, Elizabeth Bacon Custer, also played a major role in shaping this legacy. An influential woman herself, she wrote books and gave talks, painting her husband as a brave war hero who died for a noble cause. She presented the Natives as “beasts”13, furthering the one sided interpretation of the battle. Her efforts along with Custer’s already respected reputation and the need for justification of westward expansion led to a positive widespread response to the Seventh Cavalry Monument.

“Brevet Major General George Armstrong Custer”by Matthew Brady, c. 1865, licensed under Creative Commons

It wasn’t all positive, however. Already known for his aggressive tactics in battle, Custer was criticized by some for his leadership and strategic decisions, specifically his decision to split up his troops. They suggest that he is to blame for the overwhelming U.S. loss in the Battle of Little Bighorn14. Some newspapers at the time shared these critical views. The St. Louis Globe-Democrat newspaper criticized Custer’s “rash desire to reestablish a fame somewhat beclouded by the misfortunes of the last campaign.”15 Other newspapers were sympathetic to the Native Americans, with one newspaper suggesting that Little Bighorn was “God’s punishment for the White man’s sins against the Indians16.” Although these ideas regrading General Custer’s mistakes and the U.S.’s unfair treatment of the Native Americans existed in this time period, they were not the dominant beliefs. It would take many more decades for these ideas to infiltrate public opinion as a whole.

Today

Although there was widespread criticism of General Custer at the time, the Seventh Cavalry Monument itself had few critics because it fit into the broader idea of memorializing military figures. In recent decades though, the memorial has become a focal point for discussions about historical memory. As the truth about westward expansion becomes more widely known to the public, the events of the Battle of Little Bighorn and General Custer’s legacy are put under scrutiny. Critics argue that the monument presents a one-sided narrative, glorifying U.S. military actions while ignoring the perspectives and experiences of the Native American tribes involved.

The site was originally named the Custer Battlefield National Monument shortly after it became a unit of the National Park Service in 194017. The site encompassed the Seventh Cavalry Memorial as well as the graveyard of the fallen soldiers. After the site became a topic of controversy, “resident George H.W. Bush changed the name to Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument in 1991 to recognize indigenous perspectives and those who fought at the site18“. Then, in 2003, the Indian Memorial was dedicated at the same site to honor the Native American warriors who fought in the battle. The memorial design was chosen by a design competition, led by Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument Advisory Committee. This committee was “made up of members from the Indian nations involved in the battle, historians, artists and landscape architects”, ensuring that the winning design successfully honored the Native Americans who fought. 19 Adding this monument was a smart decision, since it contextualized the Seventh Cavalry Memorial and removed some of the controversy surrounding it. A big issue with the Seventh Cavalry memorial was that before 2003, the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument only showed one side of the battle and supported the idea of westward expansion while ignoring the Native Americans’ perspective. With this new monument though, it allows visitors to see both sides of the conflict, and equally honor those who fought.

“Little Bighorn Natl Mon MT Indian Memorial” by Don Barrett is licensed under CC.

Conclusion

The Seventh Cavalry Memorial serves as a reminder of how history is remembered and who’s stories are told. While originally built to honor the U.S. soldiers who died at the Battle of Little Bighorn, the monument supports a one-sided story that glorified westward expansion and ignored the Native Americans’ perspective. Over time, public perspective of the site has changed, acknowledging both sides of the conflict. Today, with the addition of the Indian Memorial, the site challenges visitors to consider both sides of history and recognize the power that monuments have over public perception.

References

- National Park Service. “7th US Cavalry Memorial.” Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, U.S. Department of the Interior, 13 Mar. 2023, https://www.nps.gov/libi/learn/historyculture/7th-us-cavalry-memorial.htm.

- National Park Service. “Battle Story.” Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, U.S. Department of the Interior, https://www.nps.gov/libi/learn/historyculture/battle-story.htm.

- History.com Editors. “What Really Happened at the Battle of the Little Bighorn?” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 24 Nov. 2009, https://www.history.com/articles/little-bighorn-battle-facts-causes.

- American Battlefield Trust. “George Armstrong Custer.” Battlefields.org, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/george-armstrong-custer.American Battlefield Trust+1American Battlefield Trust+1

- Friends of the Little Bighorn Battlefield. “Changing Faces Last Stand Hill.” FriendsLittleBighorn.com, https://friendslittlebighorn.com/little-bighorn-changing-faces.htm.friendslittlebighorn.com+2friendslittlebighorn.com+2friendslittlebighorn.com+2

- The Historical Marker Database. “Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument.” HMdb.org, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=7022.

- The New York Times. “1863: Custer’s First Stand.” Times Insider, 4 May 2015, https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/times-insider/2015/05/04/1863-custers-first-stand/.

- EBSCO. “Analysis: Accounts of the Battle of Little Bighorn.” Research Starters, https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/military-history-and-science/analysis-accounts-battle-little-bighorn.EBSCO

- Boston Athenaeum. “Elizabeth Bacon Custer.” BostonAthenaeum.org, https://bostonathenaeum.org/news/elizabeth-bacon-custer/.

- Custer Battlefield Historical & Museum Association. “Shooting Arrows & Slinging Mud: Custer, the Press, and the Little Bighorn.” CBHMA Book Review, https://custerbattlefield.org/pdfs/report-shooting-arrows.pdf.custerbattlefield.org+4custerbattlefield.org+4Montana.gov+4

- National Park Service. “Then + Now: Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument.” NPS.gov, U.S. Department of the Interior, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/battlefields/then-now-little-bighorn-battlefield.htm.

- National Park Service. “Indian Memorial.” Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, U.S. Department of the Interior, https://www.nps.gov/libi/learn/historyculture/indian-memorial.htm.

- National Park Service. “Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument.” NPS.gov, U.S. Department of the Interior, https://www.nps.gov/libi/.

- National Park Service. “Publications: Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument.” NPSHistory.com, https://npshistory.com/publications/libi/index.htm.Wikipedia+4NPS History+4NPS History+4

- https://npshistory.com/publications/libi/index.htm#:~:text=Here%20in%20the%20valley%20of,member%20of%20his%20immediate%20command ↩︎

- https://www.nps.gov/libi/learn/historyculture/battle-story.htm ↩︎

- https://www.nps.gov/libi/learn/historyculture/battle-story.htm ↩︎

- https://www.history.com/articles/little-bighorn-battle-facts-causes ↩︎

- https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/george-armstrong-custer#:~:text=On%20June%2029%2C%201863%20Custer,known%20as%20East%20Cavalry%20Field ↩︎

- https://www.nps.gov/libi/learn/historyculture/battle-story.htm ↩︎

- https://www.nps.gov/libi/learn/historyculture/7th-us-cavalry-memorial.htm#:~:text=On%20June%2028%2C%201876%2C%20three,of%20the%20fallen%207th%20cavalrymen ↩︎

- https://www.nps.gov/libi/learn/historyculture/7th-us-cavalry-memorial.htm ↩︎

- https://friendslittlebighorn.com/little-bighorn-changing-faces.htm#:~:text=In%20July%201881%2C%20Lt.,below%20the%207th%20Cavalry%20monument. ↩︎

- https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=7022 ↩︎

- https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/times-insider/2015/05/04/1863-custers-first-stand/ ↩︎

- https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/military-history-and-science/analysis-accounts-battle-little-bighorn ↩︎

- https://bostonathenaeum.org/news/elizabeth-bacon-custer/#:~:text=All%20the%20publicity%20Libbie%20received,best%20General%20of%20the%20two.%E2%80%9D&text=Leckie%2C%20Shirley%20A ↩︎

- https://www.history.com/articles/little-bighorn-battle-facts-causes ↩︎

- https://custerbattlefield.org/pdfs/report-shooting-arrows.pdf ↩︎

- https://custerbattlefield.org/pdfs/report-shooting-arrows.pdf ↩︎

- https://www.nps.gov/subjects/battlefields/then-now-little-bighorn-battlefield.htm ↩︎

- https://www.nps.gov/subjects/battlefields/then-now-little-bighorn-battlefield.htm ↩︎

- https://www.nps.gov/libi/learn/historyculture/indian-memorial.htm ↩︎