When viewing any statue, monument or memorial on display, one would expect it to be finished; complete-looking. An “unfinished” look is exactly what makes the Portrait Monument unique. Featuring busts of three of the most prominent figures of the women’s suffrage movement, many may wonder why there is a portion of the statue left entirely unsculpted. The Portrait Monument, currently located in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda in Washington D.C., invokes meaning and legend when it comes to its uncut slab of marble.

Memorializing the Suffrage Movement

The Portrait Monument features the busts of not just one, but three important women who contributed greatly to the success of the women’s suffrage movement. These three women are Susan B. Anthony, Lucretia Mott, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906) was born in Massachusetts. Her strong belief in equality is what guided her through her life’s work, inspiring her to fight for women’s rights and the end of slavery. One of her greatest accomplishments was co-founding the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) with Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1869. Anthony passed away in 1906, just 14 years before the passing of the 19th amendment which gave many women the right to vote (Mathias).

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902) was born in New York, one of ten children. Not only did she co-found the NWSA with Anthony, she was also the primary author of the Declaration of Sentiments, a document calling for legal and social equality for women. She was the most progressive out of the three women memorialized, advocating for broader women’s rights such as property rights, divorce reform, and educational equality. When she married her husband she even refused to use the words “to obey” in their marriage vows (Michals).

The Declaration of Sentiments, a proud accomplishment of Stanton and Mott, most significantly read:

We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal;

– Declaration of Sentiments, 1848

Men and women was the most important addition to be made here, and it powerfully makes a statement in this official document.

Lastly, Lucretia Mott (1793-1880) was born in Nantucket Island, Massachusetts. A Quaker minister, Mott was not only devoted to women’s rights, but to ending slavery as well. In addition to co-writing the Declaration of Sentiments with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Mott became the first president of the American Equal Rights Association. She was a strong believer in all forms of human freedom, which many accredit to her religion (Michals).

The Artist Behind the Sculpture

Adelaide Johnson was the artist behind the Portrait Monument, unveiling her sculpture in 1921 at age 62. Johnson was not only a suffragist, but considered herself a feminist. The National Woman’s Party commissioned the monument; they were seeking a suffrage monument to celebrate these three women known as the “suffrage pioneers,” and Johnson was not only a talented sculptor, but someone passionate about the movement being memorialized.

Adelaide intentionally left the uncut marble piece with an unfinished look, to symbolize the fact that women still had a long way to go to achieve equal rights (Lange). Adelaide Johnson reflects on the deeper meaning behind her sculpture in the quote below:

No one seems to have arisen to the realization that this is something far more than the simple presentation of three busts. It is the commemoration of an epoch.

Adelaide Johnson

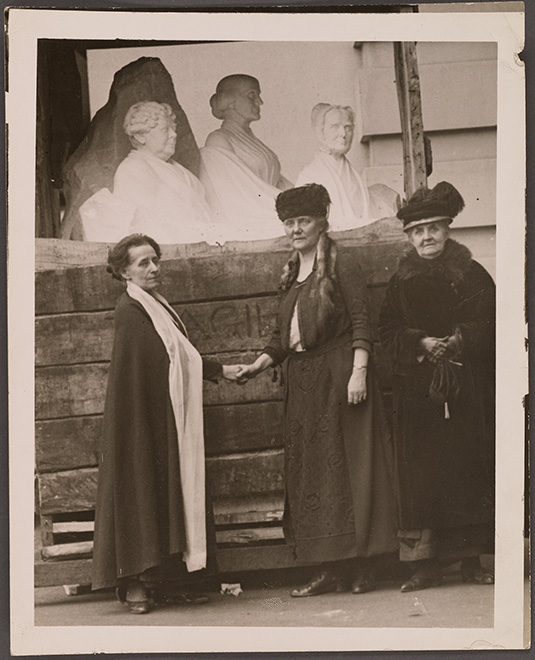

“Adelaide Johnston, sculptor, Mrs. Lawrence Lewis, Philadelphia., Jane Addams. At time statue was placed in capitol” by National Photo Co. is marked with Public Domain mark 1.0.

Invoking Meaning

This monument clearly represents Anthony, Stanton, and Mott as key leaders of the suffrage movement. It sends the message that these women were strong and talented women of their time.

I believe the most important symbolism that this monument holds is clearly represented through the uncarved piece of marble that Johnson left. By leaving a bluntly cut piece of marble next to the three complete busts, she recognized that gaining the right to vote was not the final destination of the women’s rights movement. The movement was unfinished, just like the sculpture. This sticks out to me, because even after the 19th amendment was successfully passed, Johnson knew it still remained important to recognize that there was progress to be made (Neal).

Although it is mostly agreed upon that the unfinished portion of the sculpture is meant to represent the unfinished work to be done, some have interpreted its meaning differently. It could also represent the unknown people who have fought and will fight for women’s rights. Another interpretation, one that I find most intriguing, is the urban legend that Johnson intended for the slab to be reserved for the first female president. Although there is no record of Johnson confirming or denying this speculation, it is difficult not to hope that the Portrait Monument may fulfill this idea someday in the future.

“Portrait Monument to Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony” by Harris & Ewing is marked with Public Domain mark 1.0.

Next, the story behind the inscription of this monument is particularly interesting. As I stated, the monument is currently on display in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda, although it did not always stand in this prominent location. When the National Woman’s Party presented the sculpture to Congress as a gift, they reluctantly accepted and unveiled it in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda. Shortly after this ceremony, the 26,000 pound sculpture was relocated to the Capitol Crypt. “At the time it was a service closet, with brooms and mops and the suffrage statue,” states Joan Wages, CEO of the National Women’s History Museum, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

For over 70 years, the Portrait Monument was “on display” in the Capitol Crypt, essentially the dusty, abandoned basement of the building.

Please help return the monument of the ‘mothers of woman suffrage,’ Susan B. Anthony, Lucretia Mott, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, to the Rotunda of the United States Capitol. The women in this statue emancipated one half the citizens of the United States and led the ‘world’s greatest bloodless revolution.’ Twenty-four hours after the statue, known as the ‘Portrait Monument,’ was accepted as a gift to the people of the United States on February 15, 1921, Congress moved it to a basement storage room and removed its gold leaf inscription.

– Shelley Heretyk of Off Our Backs, the longest surviving feminist newspaper in the United States, (1970-2008).

Heretyk was not the only one, though, who wanted the statue reinstated in its intended place. There were many other activists and women’s groups who fought for its relocation to the Rotunda. However, Congress continued to object. After years of excuses and many bills refused, on May 14, 1997, the statue was moved back to the Rotunda. This was a result of donations from all around the country, since the chairman of the Capitol Preservation Commission refused to use his $23 million dollar budget on the Portrait Monument, which would have cost $75,000 to move (Boissoneault).

In addition to its relocation, the sculpture was also altered. Parts of the inscription were removed, they read:

…Principle not policy; justice, not favor; Men their rights and nothing more, Women their rights and nothing less, and, Woman, first denied a soul, then called mindless, now arisen declared herself an entity to be reckoned.

The Portrait Monument Inscription, by Adelaide Johnson

These lines were viewed as particularly provocative and controversial by Congress at the time, which only further symbolizes Johnson’s point that there is still progress to be made towards equality. From the inscription, the particular portion that stands out to me is “Men their rights and nothing more, Women their rights and nothing less”. This statement radiates strength and power; it represents a call for true equality, something Johnson must have found fitting to represent the three suffrage pioneers.

Opinions Then

When the monument was first built and revealed, many women, women’s groups, and suffrage supporters thought highly of it, especially since its unveiling followed the ratification of the 19th amendment, which allowed white women to vote. But even though the monument was technically accepted by Congress, it is clear that they were not thrilled about it. At the time, the women’s rights movement was still controversial for many. Not everyone was in full support of equality. This is the exact reason why the sculpture was hidden away, instead of proudly displayed for all to see.

Later on, in the 1990’s when the process of relocating the monument back to the Rotunda had begun, there were still remaining controversies. Members of Congress argued it was “too big” “too heavy” or “too ugly.” The statue was even nicknamed “The Women in the Bathtub” because of the appearance of the three busts emerging from the large white marble slab (Boissoneault).

Opinions Now

Today, the Portrait Monument is proudly displayed in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda, a symbol of not only the success of the suffrage movement, but of the progress that has been, and is waiting to be made. Views about the monument have significantly changed since its initial unveiling, with even more supporters today.

After learning about the Portrait Monument and its detailed journey, supporters, and criticizers, it is abundantly clear that this sculpture holds a lot of meaning. Progress is still yet to be made, with activists currently fighting to get its original inscription restored. The Portrait Monument has definitely made it onto my bucket list of things to see, and I hope after hearing more about it, it has made it onto yours.

Works Cited

Boissoneault, Lorraine. “The Suffragist Statue Trapped in a Broom Closet for 75 Years.” Smithsonian Magazine, 12 May 2017, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/suffragist-statue-trapped-broom-closet-75-years-180963274/.

“Declaration of Sentiments.” Women’s Rights National Historical Park, National Park Service,

https://www.nps.gov/wori/learn/historyculture/declaration-of-sentiments.htm. Accessed 10 Dec. 2025.

Heretyk, Shelley a. “The Plight of the Woman Suffrage Statue.” Off Our Backs, vol. 26, no. 6, 1996, pp. 20–20. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20835520. Accessed 18 Nov. 2025.

Lange, Allison. Review of The Woman Suffrage Statue: A History of Adelaide Johnson’s “Portrait Monument” at the United States Capitol, by Sandra Weber. The Public Historian, vol. 40 no. 1, 2018, p. 155-157. Project MUSE, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/737494.

Mathias, Marisa. “Susan B. Anthony.” National Women’s History Museum, n.d., https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/susan-b-anthony. Accessed 10 Dec. 2025. National Women’s History Museum

Michals, Debra, editor. “Elizabeth Cady Stanton.” National Women’s History Museum, 2017. Edited and expanded by Lydia McKelvie, 2025, https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/elizabeth-cady-stanton. Accessed 10 Dec. 2025. National Women’s History Museum

Michals, Debra, editor. “Lucretia Mott.” National Women’s History Museum, 2017, https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/lucretia-mott. Accessed 10 Dec. 2025. National Women’s History Museum

Neal, Meg. “The Portrait Monument.” Atlas Obscura, 3 Nov. 2016, updated 1 Nov. 2024, https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/the-portrait-monument-washington-dc. Accessed 10 Dec. 2025.

Weber, Sandra. The Woman Suffrage Statue : A History of Adelaide Johnson’s Portrait Monument to Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony at the United States Capitol. McFarland, 2016. EBSCOhost, research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=934906a5-7a26-33ba-8fd5-059c9e6e72b8.

“WOMAN SUFFRAGE.: TRIAL OF MISS SUSAN B. ANTHONY FOR ILLEGAL VOTING THE TESTIMONY AND THE ARGUMENTS.” New York Times (1857-1922) 18 June 1873: 1. ProQuest. 10 Dec. 2025 .