Who was Abraham Lincoln?

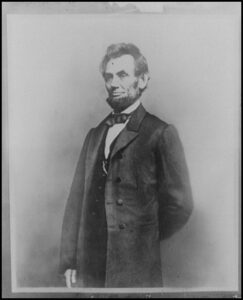

Abraham Lincoln was born in a log cabin in Hardin County, Kentucky, in 1809. As a child, his family moved several times, eventually settling in Indiana and later Illinois. Growing up in poverty, Lincoln had very little formal education, but he was largely self-taught and developed a strong interest in reading, writing, and law. As he grew older, Lincoln worked various jobs, including rail-splitting, storekeeping, and surveying, before studying law and becoming a lawyer in Springfield, Illinois. His skill as a speaker and debater helped him gain recognition in politics, and he served in the Illinois state legislature and later as a U.S. congressman.

In 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected the 16th president of the United States. Shortly after his election, several Southern states seceded from the Union, leading to the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. As president, Lincoln’s primary goal was to preserve the Union, but over time the war became increasingly focused on the issue of slavery. In 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared enslaved people in Confederate states to be free. Although it did not immediately end slavery, it changed the purpose of the war and allowed African American soldiers to fight for the Union.

Toward the end of the Civil War, Lincoln supported the passage of the 13th Amendment, which officially abolished slavery throughout the United States. Just days after Confederate forces surrendered in 1865, Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth while attending a play at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. He died at the age of 56 and is remembered as one of the most influential presidents in American history for his leadership during the Civil War and his role in ending slavery.

The History Behind the Lincoln Memorial

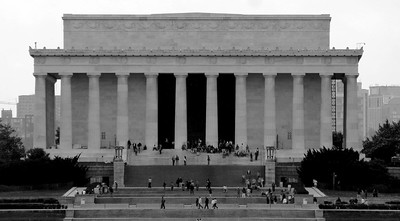

In 1910, Congress officially approved the construction of a memorial to honor Abraham Lincoln in Washington, D.C. The project was led by the Lincoln Memorial Commission, which selected architect Henry Bacon to design the structure and sculptor Daniel Chester French to create the seated statue of Lincoln. Construction began in 1914, and the memorial was built using materials sourced from across the United States, including marble from Colorado, Indiana, and Tennessee. The Lincoln Memorial was completed and dedicated in 1922, standing at the western end of the National Mall as a large, temple-like structure inspired by ancient Greek architecture. Inside, Lincoln is depicted seated and contemplative, symbolizing unity, strength, and leadership during one of the nation’s most divided periods.

The timing of the Lincoln Memorial’s construction is significant within the broader social and political climate of the early 20th century. Although Lincoln is remembered as the president who preserved the Union and helped end slavery, the memorial was built during an era when Jim Crow laws were firmly enforced and racial segregation was widespread across the country. At the dedication ceremony, African American attendees were segregated, reflecting the contradictions between Lincoln’s legacy and the realities of racial inequality at the time. Over the decades, however, the Lincoln Memorial has taken on expanded meaning, becoming a powerful symbol of civil rights and equality. It has served as the backdrop for major historical moments, including Marian Anderson’s 1939 concert and Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech, transforming the memorial into a space associated not only with remembrance but also with ongoing struggles for justice and freedom.

What is the Monument’s Message?

The Lincoln Memorial portrays Abraham Lincoln seated in a large chair, facing east toward the Washington Monument and the U.S. Capitol. His posture is calm yet commanding, with one hand clenched and the other relaxed, symbolizing both strength and compassion. Lincoln’s gaze is directed forward, meeting the viewer at eye level, which can make the audience feel as though he is watching over the nation. Unlike monuments that depict leaders in action or battle, the seated position emphasizes reflection, wisdom, and moral authority rather than physical power or aggression.

The design of the memorial reinforces this message. Lincoln’s weapons are absent, and instead the focus is placed on his thoughtful expression and composed posture, suggesting control, restraint, and responsibility. Inscriptions are carved into the interior walls of the memorial, most notably the Gettysburg Address and Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address. These texts emphasize themes of unity, sacrifice, forgiveness, and equality rather than victory or dominance. Additional inscriptions identify Lincoln’s name, lifespan, and role as the 16th president of the United States, grounding the memorial in historical fact while elevating his ideals.

Overall, the Lincoln Memorial sends a message of national unity and moral leadership. By presenting Lincoln as calm, dignified, and contemplative, the monument encourages viewers to reflect on the values he represented, particularly democracy and freedom. Over time, the memorial has become more than a tribute to one man; it stands as a symbol of hope and justice, reminding audiences that the struggle to uphold Lincoln’s ideals continues long after his lifetime.

The Past Views of the Monument

In the years leading up to the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial, Abraham Lincoln’s legacy was widely celebrated by white Americans as that of a heroic and unifying national leader. While Lincoln is best known for preserving the Union and issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, many Americans at the time focused more heavily on his role as a statesman and war leader than on the full implications of his actions for racial equality. This selective memory allowed Lincoln to be praised in a way that did not directly challenge the racial hierarchy that remained firmly in place during the early 20th century, when segregation and Jim Crow laws were widely accepted.

Lincoln’s own words were frequently used to support this interpretation of his legacy. One of the most prominent inscriptions inside the Lincoln Memorial comes from his Second Inaugural Address, delivered in 1865, in which he emphasized reconciliation rather than punishment:

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds…

This passage reinforced the idea of Lincoln as a figure of forgiveness and national healing, which resonated strongly during the memorial’s dedication. However, the celebration of Lincoln’s legacy often overlooked the fact that true equality had not been achieved for African Americans. At the dedication ceremony in 1922, Black attendees were segregated, highlighting the gap between Lincoln’s ideals and the social realities of the time.

Much like how Confederate monuments reflected the “Lost Cause” ideology in the South, the Lincoln Memorial reflected a national desire for unity without fully confronting ongoing racial injustice. While the monument honored Lincoln’s vision of a reunited nation, it also existed within a society that continued to deny many Americans the freedoms Lincoln fought to protect. Over time, the meaning of the memorial has evolved, becoming a powerful site for civil rights activism and a reminder that Lincoln’s work remained unfinished.

The Present Views of the Monument

Though the Lincoln Memorial has long been widely accepted and revered, interpretations of its meaning have evolved over time as social values and historical understanding have changed. Unlike monuments dedicated to Confederate leaders, the Lincoln Memorial has not faced serious calls for removal, but it has become the subject of debate regarding how Abraham Lincoln’s legacy is understood and presented. As conversations surrounding race, equality, and historical memory expanded in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, some critics began to question whether Lincoln should be remembered solely as a liberator, pointing instead to his complicated views on race and his initial prioritization of preserving the Union over ending slavery.

For some Americans, the Lincoln Memorial represents progress, justice, and the promise of equality. Supporters emphasize Lincoln’s role in issuing the Emancipation Proclamation and supporting the 13th Amendment, viewing the memorial as a symbol of freedom and democratic ideals. Many also highlight how the site has been reclaimed as a powerful space for civil rights activism, most notably during the 1963 March on Washington, when Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech. From this perspective, the memorial reflects not only Lincoln’s legacy but also the ongoing struggle to achieve the equality he envisioned.

On the other hand, some scholars and activists argue that the memorial can oversimplify Lincoln’s legacy and obscure the contributions of enslaved people and Black Americans who fought for their own freedom. They note that Lincoln’s image has often been used to promote national unity while avoiding deeper discussions about systemic racism and unfinished civil rights issues. This tension has led to broader conversations about how historical figures are commemorated in public spaces and whose stories are emphasized. Rather than calling for its removal, these debates have encouraged reinterpretation of the Lincoln Memorial as a site that invites critical reflection on both the progress made and the work that remains in achieving true equality.

Works Cited

“Abraham Lincoln’s Presidency | Civil War and Reconstruction, 1861-1877 | U.S. History Primary Source Timeline | Classroom Materials at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress.” The Library of Congress, 2015, www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/civil-war-and-reconstruction-1861-1877/lincoln/.

Belz, Herman. “Abraham Lincoln and American Constitutionalism.” Review of Politics, vol. 50, no. 2, Apr. 1988, pp. 169–97. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0034670500015631.

Grinspan, Jon. “‘Young Men for War’: The Wide Awakes and Lincoln’s 1860 Presidential Campaign.” Journal of American History, vol. 96, no. 2, Sept. 2009, pp. 357–78. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/96.2.357.

Lennon, Conor. “Slave Escape, Prices, and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.” Journal of Law & Economics, vol. 59, no. 3, Aug. 2016, pp. 669–95. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1086/689619.

“Lincoln Memorial (U.S. National Park Service).” Nps.gov, 2024, www.nps.gov/linc/index.htm.

“Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address – Lincoln Memorial (U.S. National Park Service).” Nps.gov, 2020, www.nps.gov/linc/learn/historyculture/lincoln-second-inaugural.htm.

Schwartz, Barry. “Collective Memory and History: How Abraham Lincoln Became a Symbol of Racial Equality.” The Sociological Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 3, 1997, pp. 469–96. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4121155.

“The Lincoln Memorial.” Art and Progress, vol. 3, no. 1, 1911, pp. 399–401. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20560520.

“THE LINCOLN MEMORIAL.” The New York Times, 13 Feb. 1914, www.nytimes.com/1914/02/13/archives/the-lincoln-memorial.html.