“Louis Armstrong Park New Orleans March 2013”

by Miguel Discart licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Throughout history, many figures have been discussed and commemorated for their actions concerning civil rights, like Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, Harriet Tubman, and Frederick Douglass. However, it is not usually noted that not every figure who actively changed the way African Americans were viewed was an active participant in the civil rights movement. Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong significantly changed how African Americans were considered in the jazz scene and how jazz was viewed overall. His musical debut from properly learning trumpet in a prison to being memorialized through a park dedicated to him despite racial troubles should be more publicly acknowledged by those learning about racial injustice and given credit in addition to the civil rights leaders.

“Satchmo”

On August 4ᵗʰ, 1901, Louis Armstrong was born in New Orleans. His childhood was as normal as every other kid’s until Armstrong reached the 5ᵗʰ grade, where he was forced to drop out of school to begin working for the family. While Armstrong was employed by his first employer, the Jewish Karnofsky family, he began setting aside money from each paycheck and began saving up. Once he had enough saved, he bought himself his first Cornet, a trumpet-like instrument designed with a shorter bore, which produces a warmer and mellower sound compared to the trumpet, which makes a brighter sound. He continued to work for the Jewish Karnofsky family until the age of 11 when he was arrested for shooting a pistol in celebration of New Year’s Eve. He was sent to the Colored Waif’s Home for Boys, where he was kept there from 1912 to 1914. While he was at the Colored Waif’s Home for Boys, he joined the Waif’s Home Brass Band. Up until the point when he joined the Waif’s Home Brass Band, he was teaching himself how to play the cornet without any mentor or guidance, so his playing for the brass band allowed him to learn and solidify proper playing techniques on the cornet under guidance. By the time he was released, his playing significantly progressed, and he became the leader of the Waif’s Home Brass Band.

“Louis Armstrong’s First Cornet”

by Wayne Hsieh is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Since his release from the Colored Waif’s Home for Boys, he continued to practice his cornet, perfecting the instrument. In 1922, Joe “King” Oliver, a jazz bandleader, invited Armstrong to play in his band in Chicago. Armstrong agreed and began to play cornet in “King” Oliver’s band. While Armstrong was in the band, he met Lillian Hardin, the pianist of the band. Armstrong fell in love with her, and they got married in 1924. After they got married, Hardin recognized the talent Armstrong had when it came to cornet. She encouraged Armstrong to branch out from “King” Oliver’s band to try and start a solo career in cornet, insisting he would make it far in the music industry. Armstrong decided to listen to her and left the band to start a career in New York, playing with Fletcher Henderson and His Orchestra. However, Armstrong felt unsatisfied making music in New York, and liking the music scene in Chicago, returned to Chicago a year later to begin his solo career there instead.

In his solo career, Armstrong has composed more than fifty songs, with many of them becoming staples to the jazz scene today, such as “West End Blues” (1928), “When The Saints Come Marching In” (1938), “Mack The Knife” (1955), “Hello, Dolly!” (1963), “What A Wonderful World” (1967), and many more. Although, Armstrong’s impact on the jazz community goes further than his hit songs, as he started and fostered jazz traditions that are still upheld today. One example is scat singing, which he popularized through his performance of “Heebie Jeebies” (1926), which is still used in jazz today. He had a natural talent for scat singing due to the rough texture of his naturally largemouth, which is where Armstrong got the nickname “Satchmo”, as it is short for “Satchelmouth”. In addition, Armstrong also rewrote the traditions of jazz soloing, making improvisation more popular in jazz scores. Before Armstrong’s career, jazz musicians were more reliant on written solos in jazz scores, and although improvisation was a type of soloing, it was not frequently used. However, when Armstrong debuted his All-Star big band, he used improvisation more frequently than written solos, leaving jazz composers and other big bands impressed. This led jazz composers and other big bands to begin utilizing the art of improvisation, giving musicians full creativity to hone their natural talents in front of audiences. Because of the difference Armstrong has made in the musical scene, he has had the opportunity to be a part of a total of 28 films and documentaries to demonstrate the relationship between society and jazz over four decades. This not only increased his fame but allowed people to have a better understanding and appreciation of jazz music.

However, given the period when Armstrong was emerging to fame, he did come across some racial injustice, specifically with his reputation. Even though everything Armstrong was doing was a positive step in the jazz community, the press, both white and black presses, still set him up to be viewed in a negative light. When the white press criticized Armstrong’s career, they would use racist language trying to invalidate his career because he was just an African American. The Black Presses, although they acknowledged his career, did not approve of it, as they claimed he was “reinforcing stereotypes” because he didn’t have a problem with people making comments about his naturally big mouth, which was a common stereotype for African Americans., and the black press would claim Armstrong was trying to please white people by doing this. With both white and black presses viewing Armstrong in a negative light because of his race in some form, it was a challenge for Armstrong to get out there and please an audience despite the natural talent he had. However, despite the racial injustice that posed Armstrong, he was still able to be the first African American in history to make specific accomplishments, such as being the first African American to host a radio broadcast and the first African American jazz musician to publish an autobiography. In addition, the films and documentaries mentioned before that Armstrong had been in were also able to relieve some of the racial injustice Armstrong had against him, as the gathering of community and jazz Armstrong was able to create led to people gaining more respect for African Americans in general.

However, Armstrong’s career was put to a halt after he began to experience medical difficulties. He had his first heart attack in 1959, and although he was okay afterward, was admitted to Beth Isreal Hospital for heart and kidney problems in 1968. Once released from the hospital, he was advised not to continue playing, as playing a brass instrument can temporarily raise your blood pressure, which was considered dangerous for Armstrong given his heart problems. However, he did not follow the hospital’s advice and continued to practice daily to keep the skills that he had and started to perform again in 1970. Since he started performing again, his health seemed fine, but on July 6ᵗʰ, 1971, Armstrong passed away in his sleep in his home in Queens, days before his 71ˢᵗ birthday.

Louis Armstrong Park

Shortly after Armstrong’s death, the city of New Orleans recognized the impact Armstrong had made on the community, and that he should be memorialized for it. Taking land that was reserved for the cultural center project (similar to the Lincoln Center in New York) that was canceled, the city of New Orleans developed Louis Armstrong Park as an urban renewal project, which was officially opened on April 15ᵗʰ, 1980. The park contains three performance centers, Congo Square, the Mahila Jackson Theater for the Performing Arts, and the Municipal Auditorium. Congo Square however has a history that goes beyond Louis Armstrong Park, as the open space was utilized by enslaved and free African Americans to share their African heritage through music before Louis Armstrong’s time, which perfects the placement of Louis Armstrong Park, as the park can represent not only the impact Louis Armstrong has made on both African Americans and the jazz community, but also where African Americans started. Today, Louis Armstrong Park is used not only for standard recreational use but also hosts various events year-round that celebrate music as a general, with staple events being the Congo Square New World Rhythms Festival (March) and Jazz in the Park (October). Additionally, local groups frequently host their concert series at Louis Armstrong Park as well.

“New Orleans – Tremé: Louis Armstrong Park – Congo Square”

by Wally Gobetz licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

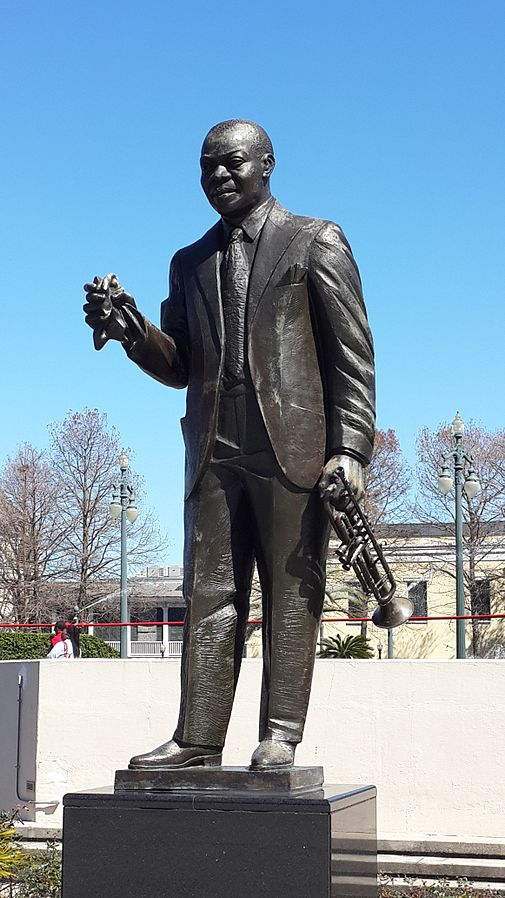

“Larger Than Life” – Louis Armstrong Park’s Main Attraction

Although the entirety of Louis Armstrong Park commemorates Armstrong, the “Larger Than Life” statue is the main statue of the park that is used to memorialize Louis Armstrong and his career. “Larger Than Life” is a bronze statue that is located in the middle of the park and was sculpted by Elizabeth Catlett in 1978. Elizabeth Catlett is an American and Mexican sculptor and was best known for her depictions of African Americans in the 20ᵗʰ century. Although “Larger Than Life” is the main staple of the park, the statue was not originally sculpted for the park and was originally in Congo Square before the development of Louis Armstrong Park, where the developers then found it more fit to move the statue to the middle of the park to better commemorate Louis Armstrong. The statue represents the legacy of Louis Armstrong and his musical influence through symbolism, as he has his trumpet in his left hand and a rag in his right, which he used to wipe his naturally big mouth when singing, making it just as important as his trumpet.

“Louis Armstrong statue-New Orleans.”

by Yair Haklai licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Works Cited

“Hometown honors Satchmo.” The Salina Journal, 16 April 1980, pp. 2. Newspapers.com, https://newscomwc.newspapers.com/image/328418/?match=1&terms=%22Louis%20Armstrong%20Park%22&pqsid=-CUoYsm3-DkGBMGenVjPkA%3A905402%3A229022801. Accessed 16 Dec. 2024

“Louis Armstrong Biography.” Louis Armstrong House Meusuem, 2024, https://www.louisarmstronghouse.org/biography/. Accessed 16 Dec. 2024

“Louis Armstrong Park.” Music Rising at Tulane, N.D., https://musicrising.tulane.edu/discover/places/louis-armstrong-park/#:~:text=The%20opening%20of%20the%20Louis,10%20pm%20from%20its%20opening. Accessed 16 Dec. 2024

“Louis Armstrong Park.” The Cultural Landscape Foundation, N.D., https://www.tclf.org/louis-armstrong-park#:~:text=Named%20to%20commemorate%20the%20talented,the%20entryway%20of%20Tivoli%20Gardens. Accessed 16 Dec. 2024

“Louis Armstrong Park Celebrates the History and Natural Charm of New Orleans.” How to Make Money and Create Community with Monuments, vol. 1, N.D. The Monumentous, https://themonumentous.com/louis-armstrong-park-new-orleans/#:~:text=The%20landscape%20surrounding%20the%20park,of%20a%20city%20and%20region. Accessed 16 Dec. 2024

“Louis Armstrong, Satchmo, Dies at The Age of 71.” The Kane Republican, 06 Jul. 1971 pp. 1. Newspapers.com, https://newscomwc.newspapers.com/image/71401091/?article=6b849638-5eb7-47dd-8f6f-2796b0a60d9b&terms=Louis%20Armstrong&pqsid=-CUoYsm3-DkGBMGenVjPkA%3A47464%3A623719392. Accessed 16 Dec. 2024

“Louis Armstrong Statue.” A People’s Guide, 31 March 2021, https://apeoplesguide.org/sites/louis-armstrong/#:~:text=Armstrong’s%20statue%20was%20created%20by,Act%20of%201965%20was%20passed.. Accessed 16 Dec. 2024

Marcus, Frances Frank. “Developing Louis Armstrong Park: to jazz it up or not?” Oakland Tribune, vol. 110, no. 100, 10 April 1983, California Digital Newspaper Collection, https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=OT19830410.1.45&srpos=4&e=——198-en–20–1–txt-txIN-%22Louis+Armstrong+park%22——-. Accessed 16 Dec. 2024

Meckna, Michael. “Louis Armstrong in the Movies, 1931–1969.” Popular Music & Society, vol. 29, no. 3, July 2006, pp. 359–73. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1080/03007760600670489. Accessed 16 Dec. 2024

Moore, Alahna and Charles Chamberlain. “Louis Armstrong Park.” New Orleans Historical, https://neworleanshistorical.org/items/show/1328. Accessed 16 Dec. 2024

Pelote, Vincent. “Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong by Ricky Riccardi (Review).” Notes, vol. 78, no. 2, Dec. 2021, pp. 1–4. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1353/not.2021.0099. Accessed 16 Dec. 2024

“Ten songs to celebrate Louis Armstrong.” Oh! Jazz, N.D., https://www.ohjazz.tv/mag/louis-armstrong-best-songs. Accessed 16 Dec. 2024

“The Museum Frequently Asked Questions.” Louis Armstrong House Meusuem, 2024, https://www.louisarmstronghouse.org/biography/. Accessed 16 Dec. 2024

“Trumpeter Marsalis kicks off weeklong celebration of jazz.” The Index-Journal, 19 April 2006, pp. 16. Newspapers.com, https://newscomwc.newspapers.com/image/70278604/?match=4&terms=Louis%20Armstrong%20Park&pqsid=l8NvLhZDDhC-gmCSg8pI5w%3A8434%3A1674161645. Accessed 16 Dec. 2024