While some individuals in the middle ages thought that acquiring the black death may have been a punishment for their sins during the time, we can now blame this plague on a pesky little bacterium known as Y. pestis. This bacterium infects the host, normally fleas, which then latch themselves onto rats in order to feed themselves. When these rats die, the fleas are left looking for another organism that can supply them with enough blood to give them sustenance; this is where humans come in. When this flea infected with Y. pestis bites a human, it transmits the infection which will lead to this individual’s demise most of the time (Stenseth et al., 2008). While these events may seem completely random, this is not entirely the case. There are many factors that can be considered to predict who in society gets attacked by this poor infected flea. One of these factors is socioeconomic status. Socioeconomic status is the social class of an individual, and it is frequently measured by their levels of income and education. Socioeconomic class, more often than not, reveals how accessible things like proper nutrition, access to clean water, and overall basic necessities an individual needs to survive are (Winkelby et al., 1992).

During the plague, a visual representation of death and equality was created, this artistic response in such bleak and distressing times represents the inevitability of death.

This painting, created in Estonia by Bernt Notke in the late fifteenth-century, shows all individuals from different socioeconomic classes and statuses dancing with death. This dance of death is meant to show that death will reach everyone, and this is one hundred percent true, but it is not considering the rate at which some of these individuals from certain classes succumb to death. The data that supports this claim was gathered by researchers using heriots, which are tributes paid to a landlord by the family of a recently deceased tenant. This data shows that in medieval England, during the first wave of the plague (1347-1351), those of a wealthy status had a mortality rate of around 4.5 percent while the poorer working class had an average mortality rate of 60 percent (DeWitte & Kowaleski, 2017). This difference in mortality rates is due to the wealthy being able to eat healthier food and have adequate sanitary conditions, which reduces the number of rats present in their houses. These factors increased the overall health of these individuals, which in turn led to a lower rate of getting infected and a higher survival rate if they were somehow infected (DeWitte & Kowaleski, 2017)

One might assume that such disparities are a thing of the past, but in fact these are still seen during more present times like the bubonic plague of San Francisco in 1907 and the 1918 Spanish flu. The Plague in san Francisco affected Chinese immigrants the most due to their living conditions; they did not have enough money to pay for proper housing which made their living spaces more rat and disease prone (Chase, 2004). The Spanish flu, which is transmitted by respiratory droplets, resulted in a slightly higher death rate in immigrant communities since they could not afford spacious housing. This led to an easier transmission for this airborne disease and as a consequence, higher mortality rates (Crosby, 1989).

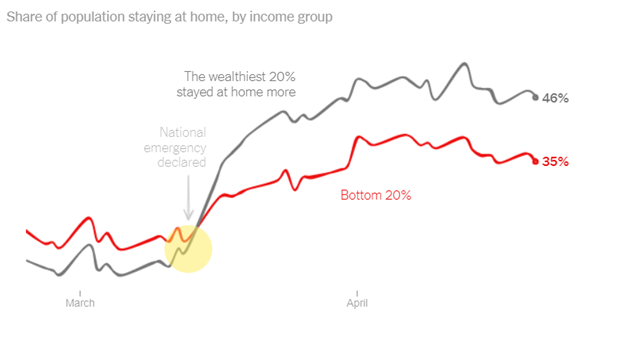

COVID-19 has not been an exception to these inequalities in the United States. It is known that Covid-19 is an airborne disease and the best way to avoid contracting it is by limiting social interactions and staying home when it is possible. Based on 2020 statistics, the rate at which the wealthy and the poor stayed at home after the Covid-19 pandemic reversed.

This caused a shift in who was most likely to get infected by the virus. The lower-class population cannot stay at home due to the fact that they cannot afford the same online delivery services that wealthy individuals can. They cannot afford to not go to work because they could face food and shelter insecurity (The New York Times, 2020).

Lower-income workers, many of whom are people of color, were much more likely to get infected. Once sick, people of color were about two to three times as likely to die of Covid as white Americans.

The New York Times

As time goes on and medical advances help find a way to slow the spread of the disease and find ways to trigger protection from the virus there is a global dilemma of “who can afford the vaccine?” (McCann & Matenga, 2020). On April 14th, 2021 an article by the New York Times was published stating that the less expensive vaccines Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca, which are crucial for third world countries, are being rejected by individuals due to the recent news of a blood clotting side effect which is caused by immunization through these vaccines. This could lead to a spike in Covid-19 cases, and the issue is that these countries cannot afford the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines which are FDA approved. It has gotten to the point where in Africa, some vaccinated individuals are looking for ways to get rid of the already administered dose of the vaccine due to the panic of this deadly side effect (Mueller, 2021).

Socioeconomic inequalities have been predictors of the odds of survival during pandemics since the abovementioned Black Plague. The lower an individual’s status the more probable they are to succumb to these bacterial and viral infections that cause these pandemics and so much death. Conversely, there is an observable decrease in mortality rates as we get closer to those individuals in the higher spectrum of status, so while everyone may dance with death some are nearing it more than others due to these external factors.

Works cited:

Chase, M. (2004) The Barbary Plague: The Black Death in Victorian San Francisco. Random House.

Crosby, A.W. (1989) America’s Forgotten Pandemic. Cambridge University Press.

DeWitte, S.N., & Kowaleski M. (2017) “Black Death Bodies – University of Michigan.” Black Death Bodies, quod.lib.umich.edu/f/frag/9772151.0006.001?view=text;rgn=main.

McCann, G., & Matenga, C. (2020). COVID-19 and Global Inequality. In Cannon C. (Author) & McCann G., Carmody P., Colleran C., & O’Halloran C. (Eds.), COVID-19 in the Global South: Impacts and Responses (pp. 161-172). Bristol: Bristol University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv18gfz7c.22

Mueller, Benjamin. “Western Warnings Tarnish Vaccines the World Badly Needs.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 14 Apr. 2021, www.nytimes.com/2021/04/14/world/europe/western-vaccines-africa-hesitancy.html.

Serkez, Y. (2021) “We Did Not Suffer Equally.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 11 Mar. 2021, www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/03/11/opinion/covid-inequality-race-gender.html?action=click&module=Opinion&pgtype=Homepage.

Stenseth NC, Atshabar BB, Begon M, Belmain SR, Bertherat E, Carniel E, et al. (2008) Plague: Past, Present, and Future. PLoS Med 5(1): e3. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050003

Winkleby, M. A., Jatulis, D. E., Frank, E., & Fortmann, S. P. (1992). Socioeconomic status and health: how education, income, and occupation contribute to risk factors for cardiovascular disease. American journal of public health, 82(6), 816–820. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.82.6.816

Excellent!!