“It’s pretty clear that what (the rise in cases) we’re seeing is directly tied to the end of the stay-at-home order” (Stobbe). Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, individual states have set public health policy for themselves, but it has not always been that way. In the last great pandemic that swept through the United States, the 1918 Spanish Flu, this kind of statewide response was rare. For the most part, each city or local area was forced to fend for themselves, with oftentimes disastrous outcomes.

In 1918, the First World War was beginning to draw to a close as the United States committed their forces to the Allied Powers. This mass troop movement set the stage for one of the most virulent flu outbreaks the world has ever seen, the 1918 Spanish Flu. When it made landfall in the United States, the virus swept rapidly from coast to coast, catching many areas off guard. This lack of preparedness, coupled with the nation’s focus on the war effort over that of the flu, caused the epidemic to have more pronounced effects upon these areas, which was further compounded by the lack of outside help. One such area was Philadelphia, which ended up enduring “three months of horror.” (Stetler). With no outside help from the state of Pennsylvania, and only a few recommendations on how to lessen the spread of disease from the US Public Health Service, Philadelphia had to look inwards for resources to stem the outbreak. However, even with emergency hospitals opened by the staff and medical students of the University of Pennsylvania, and the service of over two thousand nuns as nurses, the magazine Variety still ended up printing “It (the epidemic) has gotten to the stage when the spread of the plague has grown beyond the control of the health officials, and all that can be done is to exert the utmost and wait for an abatement of the disease.” (Stetler). Despite stretching the available resources, Philadelphia’s public health system was overwhelmed by the Spanish Flu, and the city faced tens of thousands of deaths by the time the disease had run its course.

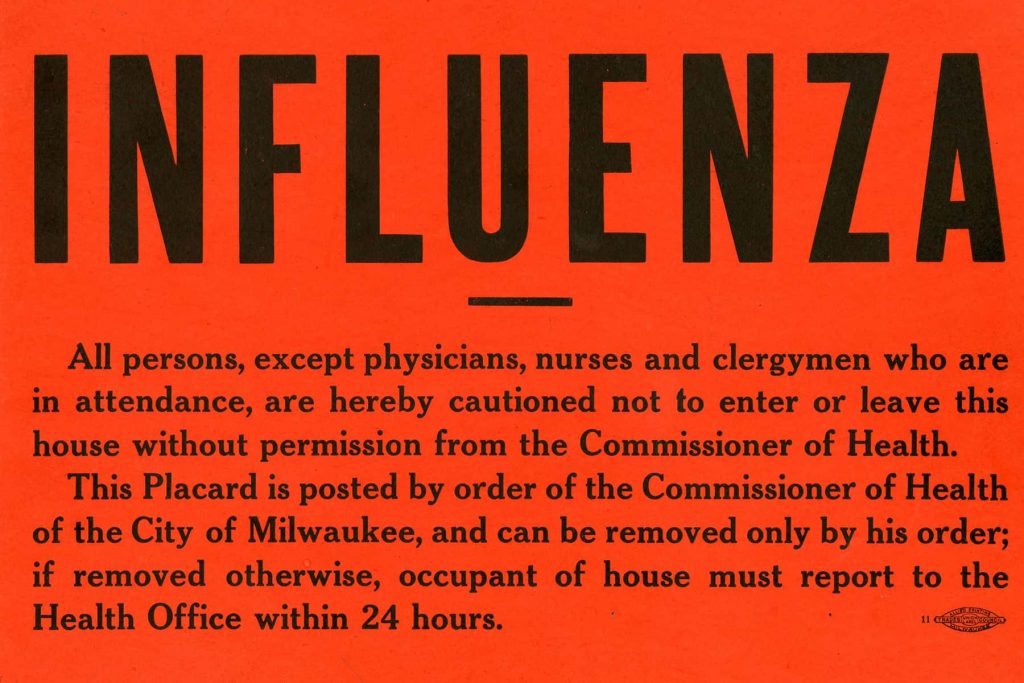

However, there were exceptions to this model, such as the state of Wisconsin, which coordinated its resources to launch a statewide public health effort to contain and lessen the spread of the flu. The existence of a state Board of Health “with unusually broad powers, allowing it to impose statewide quarantines unilaterally in times of public health emergencies” meant that Wisconsin was more prepared to quickly act and allocate its resources as needed when the flu reached the state. The State Health Officer Dr. Cornelius A. Harper also was essential in Wisconsin’s strategy as he launched an educational campaign before the epidemic even hit the state, leading to a more prepared public. He also mandated the creation of hundreds of local health boards that all reported to him, which allowed the state response to have up to date information and to disseminate information quickly. These comprehensive and coordinated methods were successful, especially when compared to how other states fared in the Spanish Flu pandemic, as shown by the fact that Milwaukee had “one of the lowest death rates of all cities of its size” (Burg). However, it must be acknowledged that a large part of the success of the state of Wisconsin’s efforts was the willingness of the state’s people and local governments to commit to and follow the guidelines set by the Board of Health and its State Medical Officer.

(http://www.milwaukeeindependent.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/032420_InfluenzaSign_MKE.jpg)

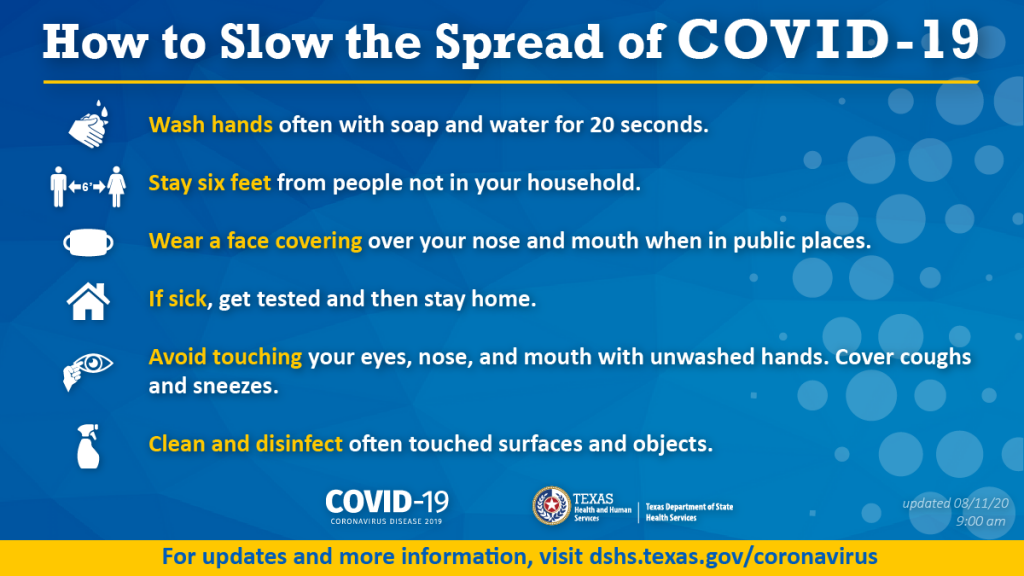

When the COVID-19 pandemic reached the United States, it seems that some of the lessons from 1918 had been learned, as every state responded to the pandemic with a coordinated statewide response, although the time to implement them and the intensity of the response varied by state. However, a statewide response alone does not guarantee success in the face of a pandemic; even though a coordinated response means areas in dire need have a better chance of receiving needed resources, policy mistakes can still lead to surges in cases. This became the case in several states, such as Arizona, Texas, and North Carolina, in May and June 2020, where a premature easing in stay-at-home orders and restrictions lead to large increases in cases in all three states. Such large increases placed undue strain on these states’ public health structures, with Arizona having 83% of its hospital beds full, Texas reaching among the nation’s highest positivity rates, and North Carolina seeing its highest increases since the beginning of the pandemic (Stobbe). Some of these issues arise from misguided policies, such as the early reopening in North Carolina and Arizona, while others arise from the public’s pushback against such measures, as it is in Texas. Ultimately, even a centralized statewide effort, while a more effective means of combatting a large-scale epidemic, is not inherently foolproof, and fighting an outbreak requires committal and support in order to succeed.

With the shift from typically locally driven community efforts during the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic to more centralized statewide efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is possible to speculate that this trend towards centralization may result in the federal government, with organizations such as the Center for Disease Control, playing a large role in public health efforts in the next great pandemic. However, evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic indicates that this may not necessarily be the case, as there were many instances of state and federal government authorities clashing over policy and resources, with the most prominent figures being President Donald Trump and Governor of New York State Andrew Cuomo. Governor Cuomo blamed President Trump for New York’s early troubles with the virus, as New York was one of the first largescale outbreaks in the United States, citing a lack of information given as a failure by the federal government (Pengelly). This rivalry extended to the development of the vaccines for the COVID-19 virus, which were largely funded and approved by the federal government, with Governor Cuomo stating that he believed President Trump would potentially rush the vaccine. In response, Governor Cuomo stated that he would not approve any United States made vaccine for use in New York State until the state reviewed the vaccine with its own team of scientists and deemed it safe for use (Mann). These clashes between state and federal executive figures put a damper on any federal assistance for the state of New York and indicate the difficulties of trying to fully centralize a public health response across the nation.

(https://media-cldnry.s-nbcnews.com/image/upload/newscms/2021_17/3468827/210428-andrew-cuomo-ac-1018p.jpg)

Another issue that has appeared with a potential federal centralization of disease response is the issue of disseminating resources over such a vast area and diverse population as that of the entire country, which has already been shown by the distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine. President Biden had made a statement claiming that every adult in the United States would be vaccinated for COVID-19 by the end of May 2021, but as of the end of March 2021, only one state, Wyoming, was the only one on track to do so (Arsenault). This indicates that not only would political clashes limit the effectiveness of a centralized federal response, but the infrastructure is also currently not in place to facilitate one, and implementing one would likely be of tremendous cost, casting doubt on the possibility of it.

Despite the strength of a statewide, uniform response, a weakness can emerged when those in charge of the effort do not listen to the science. During the COVID-19 pandemic, certain states, particular majority conservative states, such as Florida used the power of a centralized health response to create a statewide nonresponse. Governor Ron DeSantis of Florida issued an executive order on September 25th, 2020 that prohibited local governments from fining people that broke mask mandates and other measures implemented to lessen the spread of COVID-19 (Persaud). This order is speculated to have worsened the effect of a large surge in cases in Florida following the influx of spring break vacationers after the order came into effect. This incident, along with several similar ones in other states, shows how the power of a centralized response can be actively harmful it is used to counteract efforts to stop a pandemic.

While it would appear that the United States has learned some lessons from the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic, namely that a more centralized statewide response is a more effective means of combatting widespread outbreaks, it seems that there is still more to learn. The unity and diligence in following the guidelines set by the Wisconsin Board of Health in 1918 was not observed in several states in the COVID-19 pandemic, and as a result, cases began to climb. It is possible that this is a lesson that will be learned from this modern-day pandemic, but only time will tell what will be learned and preserved for the next great pandemic.

Works Cited

Arsenault, Anisa. “COVID-19 Vaccine Distribution Tracker: Week of March 22.” Verywell Health, 30 Mar. 2021, www.verywellhealth.com/covid-19-vaccine-distribution-tracker-week-of-march-22-5119532.

Burg, Steven. “Wisconsin and the Great Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 84, no. 1, 2000, pp. 36–56. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4636887. Accessed 20 Apr. 2021.

Mann, Brian. “Cuomo Says N.Y. Health Officials Will Review Any U.S.-Approved COVID-19 Vaccine.” NPR, NPR, 24 Sept. 2020, www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/09/24/916565352/cuomo-says-n-y-health-officials-will-review-any-u-s-approved-covid-19-vaccine.

Persaud, Chris. “DeSantis Orders Worsened Spring Break COVID Surge, Mayors Say.” The Palm Beach Post, Palm Beach Post, 15 Apr. 2021, www.palmbeachpost.com/story/news/2021/04/15/desantis-orders-worsened-spring-break-coronavirus-surge-mayors-say/7140623002/.

Stetler, Christina M. “The 1918 Spanish Influenza: Three Months of Horror in Philadelphia.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, vol. 84, no. 4, 2017, pp. 462–487. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/pennhistory.84.4.0462. Accessed 23 Apr. 2021.

Stobbe, Mike. “Alarming Rise in Virus Cases as States Roll Back Lockdowns.” AP NEWS, Associated Press, 11 June 2020, www.apnews.com/article/arizona-ar-state-wire-az-state-wire-tx-state-wire-new-york-feb4c26d9364497cf82ee7c0c1b1b3d5.