The past year has been terribly damaging to our collective mental health. There is no vaccine for mental illness.

Michelle Williams, dean of Harvard Chan School

The importance of action has been stressed throughout the entirety of the COVID-19 pandemic. This action required us to isolate ourselves from each other, make the move to online schooling and work, and temporarily close non-essential businesses. While these actions were seen as being for the greater good and ultimately leading to saving lives, there was an aspect that nobody thought of, the impact this would have on mental health. We, as a society, are just beginning to understand and destigmatize mental health, especially as it may relate to pandemics, but there are sources that date back to The Black Death that show recognition of the impact that isolation and pandemics have on the psyche of the population.

Mental Health and Pandemics Throughout History

The Black Plague

The Plague, also known as the Black Death, occurred during the mid-1300s and is known as the most fatal pandemic in human history. Although there was a lack of understanding of disease during this period, there are a few instances where it was recognized that the plague was taking a mental toll. An early example of this is present in the Pistoia Plague Ordinances which were put in place in 1348 in response to the arrival of the plague (Buonacorsi). The ordinances outlined specific rules the people of Pistoia were required to follow or risk penalties, most commonly in the form of fines. Several of these fines revolved around the handling of bodies and who could attend funerals. One specific ordinance involving death reads:

X. Item. So that the sounds of bells might not depress the infirm nor fear arise in them [the Wise Men] have provided and ordered that the bellringers or custodians in charge of the belltower of the cathedral of Pistoia shall not permit any bell in the said campanile to be rung for the funeral of the dead nor shall any person dare or presume to ring any of these bells on the said occasion….

(Buonacorsi)

This ordinance restricts the ringing of the bells for deaths because they realized how many deaths were occurring. For the citizens, it would have been extremely depressing to constantly hear the bell toll for deaths and would also incite fear. This shows how government officials recognized that they had to intervene in order to protect the minds of the people even if they didn’t fully comprehend the impact the plague was having on mental health.

The Black Death: The Great Mortality of 1348-1350 A Brief History with Documents by John Aberth also contains sections that show recognition of the importance of preserving the mind. In this document it is again mentioned that the bells should not be rung for those who die as “the sick are subject to evil imaginings when they hear the death bells..” (Aberth, 55). Another quote from this book states “Thus, it is evidently very dangerous and perilous in times of pestilence to imagine death and to have fear. No one, therefore, should give up hope or despair, because such fear only does great damage and no good whatsoever” (Aberth, 54-55). From these quotes it can be deduced that it was believed that people’s mentality during the plague had an impact on whether or not they got sick or survived if they became ill. For this reason, it can be implied that there was some value placed in keeping a positive outlook and keeping mental health in good standing.

The Spanish Flu

The influenza pandemic of 1918, known as the Spanish Flu, is a lesser-known pandemic than the Black Death despite having made multiple waves throughout the United States and having targeted those who are generally believed to be the most resilient, those ages from 20-40. Although the connection between the 1918 pandemic and mental health is rather understudied, there are a few studies that go back and look at hospital statistics in the years following the pandemic. One of these studies looked at asylum hospitalizations in Norway from 1872-1929. This study found that the number of first-time patients with mental disorders that could be linked to influenza increased by an average factor of 7.2 throughout the 6 years following the influenza pandemic (Eghigain). It was also reported that those who survived the Spanish Flu noted having sleep disturbances, depression, mental distraction, dizziness, and difficulties coping at work, all alongside the influenza death rates which positively correlate to suicide (Eghigain). This shows how going through a pandemic and having to watch as people die by the thousands takes a severe toll. Even if a person doesn’t become sick, they may lose those who they are close to and be left with a feeling of fear and hopelessness. Those who do fall ill can be left with detrimental side effects that influence their quality of life and lead to negative thoughts and poor mental health.

COVID-19’s Impact on Mental Health

What is going on?

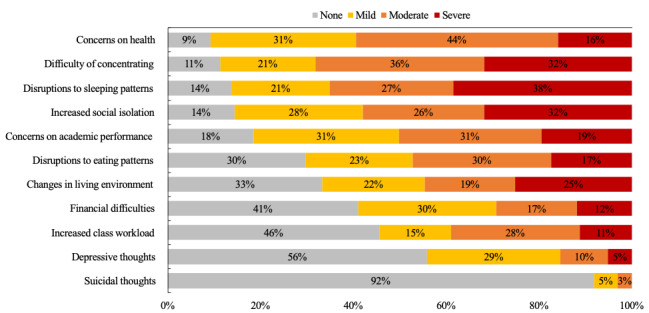

While it is difficult to understand the full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health as we are still living through this pandemic, it has become clear that one of the hardest hit demographics during this time has been college students. This is in part to the forced relocation of students in the midst of the Spring 2020 semester. A study published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research assessed the impact of this relocation on students. Students were surveyed and asked if they were required to move from campus and for those who did, their experiences and feelings were then evaluated (Conrad et al.). It was discovered that one third of the surveyed students were required to relocate and those who were among those mandated to move reported more grief, loneliness, and generalized anxiety relating to COVID-19 (Conrad et al.). Another study found that 71% of surveyed students indicated increased levels of stress and anxiety due to COVID-19 (Son et al.). Among these students, the identified stressors included fear and worry about their health as well as their families, difficulty in concentrating, disruptions in sleeping patterns, decreased social interactions, and increased concerns on academic performance (Son et al.). It was also noted that students sought support from others and also attempted to help themselves by adopting either negative or positive coping mechanisms (Son et al.). It is clear that students are struggling to cope with the stress that academics bring, alongside a change in how they are being taught, and a global health crisis. This crisis is pushing to the forefront a larger issue of students’ mental well-being, and how these issues should be handled both during an emergency, as well as under normal circumstances.

College students are not the only ones feeling the pressure. Essential workers have been on the front lines for the entirety of the pandemic. It has been reported that 34% of essential workers have received treatment from a mental health professional over the last year and 25% of them have received a mental health diagnosis (Fielding). Parents are also at a high risk. 48% of parents who responded to a survey indicated higher levels of stress, as opposed to 31% of adults who do not have kids (Fielding). The pandemic has affected everyone in different ways and on different levels of severity, but it is evident that many people’s mental health has been impacted.

The Future

When the pandemic is finally declared over, we will still be left to deal with its long-lasting effects. Dr. Anthony Fauci, who serves as the director of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the chief medical advisor to the president, expressed concern about mental health post-pandemic by saying that he is “very much so” concerned about a mental health pandemic and that “That’s the reason why I want to get the virological aspect of this pandemic behind us because the long-term ravages of this are so multifaceted” (Fielding). Within the past year, there has been an increase in the diagnosis of mental health disorders, and these diagnoses will not disappear when the pandemic is declared over. People are grieving things ranging from loved ones and broken relationships to missed opportunities and changed plans. It will be important to recognize that life will not look the same as it did before the pandemic in 2020 and that this may lead to difficulty coping with what life will look like after, since life felt like it was put on pause (Fielding). For those grieving, it is important to work through those feelings and attempt to reach a feeling of closure. Some recommendations for those who have lost someone is to celebrate their life by recounting memorable moments, partaking in their favorite activities, or even writing a letter (Fielding). For others it may be important to think about what they want their life to look like moving forward. Dr. Magavi, an adult, adolescent, and child psychiatrist and region medical director for Community Psychiatry says that “My patients have conveyed that the pandemic has helped them think about what they want more than what society expects” (Fielding). Once the pandemic is over, it will be possible for people to work on taking control of their lives again and work through the trauma that has been produced by the pandemic.

Those who have had COVID-19 are at an even greater risk for mental health issues. A recent study from Oxford University analyzed the electronic health records of over 200,000 patients from the United States who had COVID. It was estimated that the “incidence of being diagnosed with a neurological or mental health disorder following COVID-19 infection was 34%” (“Largest Study to Date Suggests Link between COVID-19 Infection and Subsequent Mental Health and Neurological Conditions”). For 13% of diagnosed people, it was their first neurological or psychiatric diagnosis (“Largest Study to Date Suggests Link between COVID-19 Infection and Subsequent Mental Health and Neurological Conditions”). While these numbers are concerning, the wide array of conditions is also concerning. Some of these conditions include headaches, debilitating fatigue, trouble thinking clearly, insomnia, anxiety, and depression (Collins; Almost 20% of COVID-19 Patients Receive Psychiatric Diagnosis within 90 Days — Department of Psychiatry). With the number of people who have contracted COVID-19 steadily increasing, these diagnoses may become more common and contribute to the potential impending mental health crisis.

Pandemics have impacted the world and left their mark on different points in history. Although the mental health impacts are not well documented, there are indications that the importance of mental health was recognized dating as far back as the mid 1300’s. Now that we are living in the midst of a pandemic, we are able to see and document in real time the impact that it has had on mental health. It is clear that the effects are serious and could lead to a mental health crisis. As we continue to navigate through these times, it is important to make mental health a priority and attempt to lessen the long-term impacts as much as possible.

Works Cited

Aberth, John. The Black Death: The Great Mortality of 1348-1350: A Breif History with Documents. Bedford/ St. Martin’s, 2005.

Almost 20% of COVID-19 Patients Receive Psychiatric Diagnosis within 90 Days — Department of Psychiatry. 10 Nov. 2020, https://www.psych.ox.ac.uk/news/20-of-covid-19-patients-receive-psychiatric-diagnosis-within-90-days.

Buonacorsi, Simone. Ordinances For Sanitation in a Time of Mortality. 1348.

Collins, Francis. Taking a Closer Look at COVID-19’s Effects on the Brain – NIH Director’s Blog. 14 Jan. 2021, https://directorsblog.nih.gov/2021/01/14/taking-a-closer-look-at-the-effects-of-covid-19-on-the-brain/.

Conrad, Rachel C., et al. “College Student Mental Health Risks during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications of Campus Relocation.” Journal of Psychiatric Research, vol. 136, Elsevier Ltd, Apr. 2021, pp. 117–26, doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.01.054.

Eghigain, Greg. “The Spanish Flu Pandemic and Mental Health: A Historical Perspective.” Psychiatric Times, 2020, https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/spanish-flu-pandemic-and-mental-health-historical-perspective.

Fielding, Sarah. “Why Our Mental Health Won’t Just Go Back to Normal When the Pandemic Is Over.” Very Well Mind, 2021, https://www.verywellmind.com/mental-health-after-pandemic-5118386.

“Largest Study to Date Suggests Link between COVID-19 Infection and Subsequent Mental Health and Neurological Conditions.” Department of Psychiatry, 2021, https://www.psych.ox.ac.uk/news/largest-study-to-date-suggests-link-between-covid-19-infection-and-subsequent-mental-health-and-neurological-conditions.

Owell, Alvin. “Pandemic Pushing People to the Breaking Point, Say Experts.” Harvard Gazette, 2021, https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2021/01/pandemic-pushing-people-to-the-breaking-point-say-experts/.

Son, Changwon, et al. “Effects of COVID-19 on College Students’ Mental Health in the United States: Interview Survey Study.” Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 22, no. 9, JMIR Publications Inc., 1 Sept. 2020, doi:10.2196/21279.