“The African Union estimated that every three months the lockdown continues, an additional 15 million cases of gender-based violence are expected.”

African Union, 5

The African Union estimated that every three months the lockdown continues, an additional 15 million cases of gender-based violence are expected (African Union, 5). Africa has been battling the plague of gender-based violence for centuries now. In the past few years, women and children were subject to fight two pandemics: domestic abuse and COVID-19. Some women even experienced three: gender-based violence, COVID-19, and HIV/AIDS. This article will compare and contrast the three pandemics and what victims experience.

COVID-19

COVID-19 was a pandemic no one could have prepared for, and even if preparation was done, I don’t believe it could have been stopped or prevented. Quarantine was the most essential step in stopping the spread of the disease, however, it left many women and children in unsafe situations at home. During the first week of lockdown, the South African Police Minister reported 87,000 complaints of gender-based violence (Nakayazze, 93). This number of reports may be shocking, but what’s even more concerning is that most cases go unreported. It is believed that the number of domestic violence happening is much higher. Women and children are intimidated to keep quiet and fear even harsher punishments if they tell anyone. In South Africa, the culture and social norms encourage that a family and its home should always be protected and that what happens within relationships should be kept between them. There are many reasons why a woman may stay in an abusive relationship, for example, having a strong emotional attachment to their partner, the fear of being judged, the stigma attached to domestic violence, the fear of embarrassing themselves, and the repercussions they may face (Nakyazze, 94). These are only a few examples of why women may stay in a relationship during normal times.

When COVID-19 was introduced, there was even more stress added onto why one should stay with their partner. The first being the economy. Prior to COVID-19 the economy was bad, and many families experienced financial insecurity. During the pandemics, businesses had to shut down and many families were left with no income. In some cases of intimate-partner violence, the man may be the only form of income. Magezi & Manzanga report that “a woman may remain with an abusive partner, because she is financially or economically dependent on him. She may be unskilled or not employed and simply a housewife with children” (Magezi & Manzanga, 3). The lack of any income during COVID-19 put more stress on relationships, resulting in more abuse. Lyons and Brewer report that “Financial abuse could, in fact, be one of the many strategies for perpetrators to prevent their victim from escaping.” (Brewer & Lyons, 1). To a male, these situations would be insulting to their ego, which results in abusive behavior (Magezi & Manzanga, 2). Another issue presented is alcohol abuse or alcohol withdrawal symptoms that abusers may experience, leading them to be violent. Finally, the lockdown prevented women and children from accessing psychological support from counselors and religious groups, making it difficult to cope with what they were experiencing (Magezi & Manzanga, 2). The African Union reported that victims were experiencing limited access to legal protection services and most hearings were suspended (African Union, 5). This could also cause violence to increase within a household because a partner is upset the other brought their issues to court. Intimate-partner violence has been a pandemic women have battled for decades. The introduction of a highly contagious virus only added to the high levels of stress and the fear of the unknown. COVID-19 was not the first pandemic during which women faced abuse: the same happened during the HIV pandemic.

“Violence, poverty, and inequality are the fault lines along which HIV spreads”

Paul Farmer

HIV/AIDS

Andrews et al. reports that intimate partner violence is one of the primary drivers of the HIV epidemic and women in poverty were at high risk of suffering intimate-partner violence and contracting HIV. There is evidence to prove that women at the highest risk of HIV are those 1. In a heterosexual marriage or long-term union in a society where men commonly engage in sex outside the union and 2. In cultures in which gender-based violence is culturally accepted. In Africa, women and girls represent 57% of people living with HIV (Watts & Seeley, 1). A range of sources report that there is a strong correlation between intimate-partner violence and HIV. The World Health Organization identified several direct and indirect ways women experiencing intimate-partner violence could contract HIV. The first being direct transmission through sexual violence, including forced or coercive sexual intercourse. The second being indirect transmission through sexual risk-taking. It’s reported that womens experience of violence is linked to increase risk-taking, for example, having multiple partners or engaging in transactional sex (Artz, et al., 377). Furthermore, women with HIV are subjected to higher levels of intimate partner violence because of their status of HIV. There are four common forms of abuse: emotional, physical, and sexual (Gibs, et al., 11). Women are also subject to a wide range of structural violence. Gibs et all. report women are coerced or forced into sterilization. They also receive poor treatment at clinics and criminalization of HIV transmission. Reports collected from women attending ante-natal clinic in Johannesberg, South Africa found that women described how HIV diagnosis during pregnancy and partner disclosure, were common triggers for violence within their relationship (Watts & Seeley, 2). The women also described how adhering to medications and services was difficult because they thought it might alert their partners of their HIV status; later resulting in more violence from keeping a secret and having HIV. Pregnant women also reported they felt unable to refuse sex or negotiate condom use. They feared their own safety and their unborn child because there is a potential for the baby to contract HIV through secondary transmission (Watts & Seeley, 2). It’s clear to see that the correlation between HIV and intimate-partner violence is strong. Women are subject to violence based on having HIV and also refusing to have sex with infected individuals. Both scenarios put women in dangerous situations that could result in violence. HIV has been around for a while now, but not nearly as long as intimate-partner violence. The correlation between the two is undoubtedly apparent. Women experienced similar yet different circumstances during the COVID-19 and HIV pandemic. Next, I will compare and contrast the two to better under both pandemics in relation to intimate-partner violence.

Compare and Contrast

COVID-19 and HIV are two very different pandemics. It’s difficult to compare them as an actual sickness because one targets the respiratory system and the other the immune system. COVID-19 can be cured in most cases; there were many deaths throughout the pandemic, but many people also survived. Within a year after the pandemic, vaccines were able to be made and administered to people. Unfortunately, places like Africa were not given vaccines until much later. Probably due to the price of the vaccines and the poverty the continent faces. HIV on the other hand is incurable and there is no vaccine against it. HIV may take 2 to 4 weeks to show symptoms, and even then, some people may not experience them. HIV ultimately results in death later on in life, however, there are a few treatment options that can prevent death. Unfortunately, these options are likely to be inaccessible to women in Africa, primarily because the medicine needs to be taken for life and is very expensive. The actual virus from both pandemics infected people in various ways. Most people were able to recover from COVID-19, but HIV is a lifetime viral infection that is difficult to treat. Despite these differences, COVID-19 and HIV are very similar in regard to women’s experience with intimate partner violence. As discussed previously, COVID-19 left many women in unsafe situations with their abuser. Quarantine was the primary cause of the increased violence. Financial problems were also a leading cause, along with alcohol abuse. During HIV there was not a quarantine period and people were getting infected at high rates. The issues with HIV and intimate partner violence came along later. The primary issue being infected men forcing women into sex without protection. Once the woman is infected, they will have the virus for life. This can result in many women staying in a relationship they don’t feel like they can leave because of their positive status. Women will be emotionally abused by being told no one will want them if they have HIV. In Africa, a lot of the issues also immerge from financial troubles. Women with HIV are not able to get treated and therefore feel even more stuck. COVID-19 and HIV presented further issues with intimate-partner violence that were not prevalent prior to the pandemics. African women have been battling three pandemics since the start of 2020 and two since the 1960s. COVID-19 and HIV are not ideal; however, they may be treatable. Intimate partner violence cannot be treated which may make it the worst pandemic known to mankind.

Works Cited

African Union Commission, et al. “Gender Based Violence in Africa during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Africa, UNWomen, 2020, africa.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/12/gbv-in-africa-during-covid-19-pandemic.

ANDREWS, COURTNEY, et al. “Intimate Partner Violence, Human Rights Violations, and HIV among Women in Nairobi, Kenya.” Health and Human Rights, vol. 22, no. 2, 2020, pp. 155–66, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27040009. Accessed 28 Apr. 2022.

Gibbs, Andrew, et al. “How Do National Strategic Plans for HIV and AIDS in Southern and Eastern Africa Address Gender-Based Violence? A Women’s Rights Perspective.” Health and Human Rights, vol. 14, no. 2, 2012, pp. 10–20, http://www.jstor.org/stable/healhumarigh.14.2.10. Accessed 28 Apr. 2022.

Klazinga, et al. “Sexual and Gender-Based Violence and HIV in South Africa: an HIV Facility-Based Study.” Sabinet: African Journals, vol. 110, no.5,1 May 2020, journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.7196/SAMJ.2020.v110i5.13942.

Lyons, M., Brewer, G. Experiences of Intimate Partner Violence during Lockdown and the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Fam Viol, 26 February 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-021-00260-x

Magezi, Vhumani, and Peter Manzanga. “COVID-19 and Intimate Partner Violence in Zimbabwe: Towards being Church in Situations of Gender-Based Violence from a Public Pastoral Care Perspective.” In Die Skriflig, vol. 54, no. 1, 2020. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/covid-19-intimate-partner-violence-zimbabwe/docview/2470848295/se-2, doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ids.v54i1.2658.

Moon, Janet E. “VIOLENCE, CULTURE, & HIV/AIDS: CAN DOMESTIC VIOLENCE LAWS REDUCE AFRICAN WOMEN’S RISK OF HIV INFECTION?” Syracuse Journal of International Law and Commerce, vol. 35, no. 1, 2007, pp. 123-157. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/violence-culture-amp-hiv-aids-can-domestic-laws/docview/197148429/se-2?accountid=41635.

Nakyazze, Brendah. “Intimate Partner Violence during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Impending Public Health Crisis in Africa.” The Anatolian Journal of Family Medicine, vol. 3, no. 2, 2020, pp. 92. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/intimate-partner-violence-during-covid-19/docview/2546656520/se-2, doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.5505/anatoljfm.2020.96967.

Watts C and Seeley J. Journal of the International AIDS Society 2014, 17:19849 http://www.jiasociety.org/index.php/jias/article/view/19849 | http://dx.doi.org/10.7448/IAS.17.1.19849

Images Cited

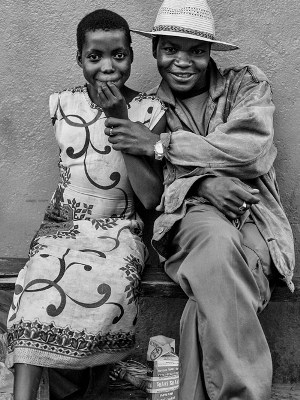

Yates, Mick. “Young Girls, Older Men, & HIV/AIDS In Africa.” Edge of Humanity Magazine, 14 June 2016, https://edgeofhumanity.com/2016/06/14/africa-5/

Bothma, Nic. “Thousands protest in South Africa over rising violence against women.” The Guardian, 5 September 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/sep/05/thousands-protest-in-south-africa-over-rising-violence-against-women