Did you know that pandemics have a major influence on the way we build and design today? Throughout the years of past pandemics such as the 1918 flu and cholera in London, even up until our most recent Covid-19 pandemic, we have learned a lot about our interiors and how they have an effect on pandemics and how pandemics have an effect on them. Some interiors and architecture actually have made pandemics worse. It’s important to know how pandemics affected interiors because now designers know what to do and what not to do, especially to help prevent certain situations and problems that come along with pandemics.

Cholera’s Effect on Interiors and Architecture

The outbreak of cholera in London had an effect on interiors and architecture, mainly the architecture throughout London, and also encouraged some cities in America to make changes to their architecture. Cholera spread in London due to contaminated drinking water because the drinking water was “laced with sewage” caused by a bad sewage disposal system (Johnson 126). During the Cholera outbreak before they discovered the contaminated drinking water, the miasma theory was established which meant that the bad air and smell in London were believed to be the cause of the Cholera outbreak. (Johnson 69). This theory leads to an increase in the installation of water closets and new sewer systems to try and control the smell and bad air. (Johnson 15).

“According to one survey, water-closet installations had increased tenfold in the period between 1824 and 1844.”

(Johnson 12)

Because of the cholera outbreak, cities in America were also making changes and had a domestic reform on plumbing which also caused Americans to begin writing and making rules about plumbing. “The outbreak of cholera in America and abroad in 1849 and John Snow’s discovery of the relationship between tainted water and disease strengthened the reform impulse” (Ogle) Starting in the 1840s architectural plan books suddenly contained a lot of detail on how to install and use water fixtures (Ogle). The Cholera outbreak impacted the way we install and control our plumbing today.

The 1918 Flu’s Effect on Interiors and Architecture

The 1918 flu also had effects on interiors and architecture. The 1918 flu caused a lot of domestic changes to interiors and architecture. Things we see today such as closets and powder rooms were influenced by the 1918 flu. Before the 1918 flu, most households kept their clothing in stand-alone furniture and closet were very tiny if they even existed in a home (Yuko). It wasn’t until after the flu that the closet became bigger or even existed. The switch to closets made rooms easier to clean, Stand-alone furniture was too big and difficult to move which lead to the collection of dust (Yuko). Dust was thought to collect and pass along germs. (Yuko). Powder rooms or half baths are also a result of the 1918 flu. Powder rooms were placed on the first floor of the home to prevent the spread of infectious diseases (Yuko). The idea of the powder room came about so guests or delivery men didn’t have to use the family bathroom in a home, just in case they were sick with something contagious, such as the flu (Yuko). The 1918 flu also had an effect on the interior medical facilities too. After the 1918 flu, there was a “major impetus to the development of newer medical facilities” (Cockrell 311). Within these new medical facilities, different materials were being used. Popular materials after the 1918 flu were white-colored tiles and linoleum flooring (Yuko). White-colored tiles become desired because they were easy to clean, it was easy to spot any dirt or grime on them (Yuko). Linoleum replaced a lot of flooring after the 1918 flu because it too was easy to clean (Yuko).“The idea of light and air being important in building design was embraced in the early part of the twentieth century” (Planner). The 1918 flu allowed for a new emphasis on bigger balconies, windows, and easy access to gardens from homes to allow for better ventilation (Planner). Designer Richard Neutra, a pioneering modernist architect, create the Lovell health house in Los angles after the 1918 flu (Budds). Lovell health house was designed after the 1918 flu for Dr.Phillip Lovell, Lovell was concerned with fresh air and light (Sisson). The Lovell health house was made up of concrete and steel which made it easy to clean and included lots of windows for ventilation. (Sisson). Interiors after the 1918 flu were designed to be easy to clean, large windows were installed, and minimal furniture was used (Planner). Overall the 1918 flu caused a lot of the things we see in interiors today and had a crucial impact on the design world.

Covid-19’s Effect on Interiors And Architecture

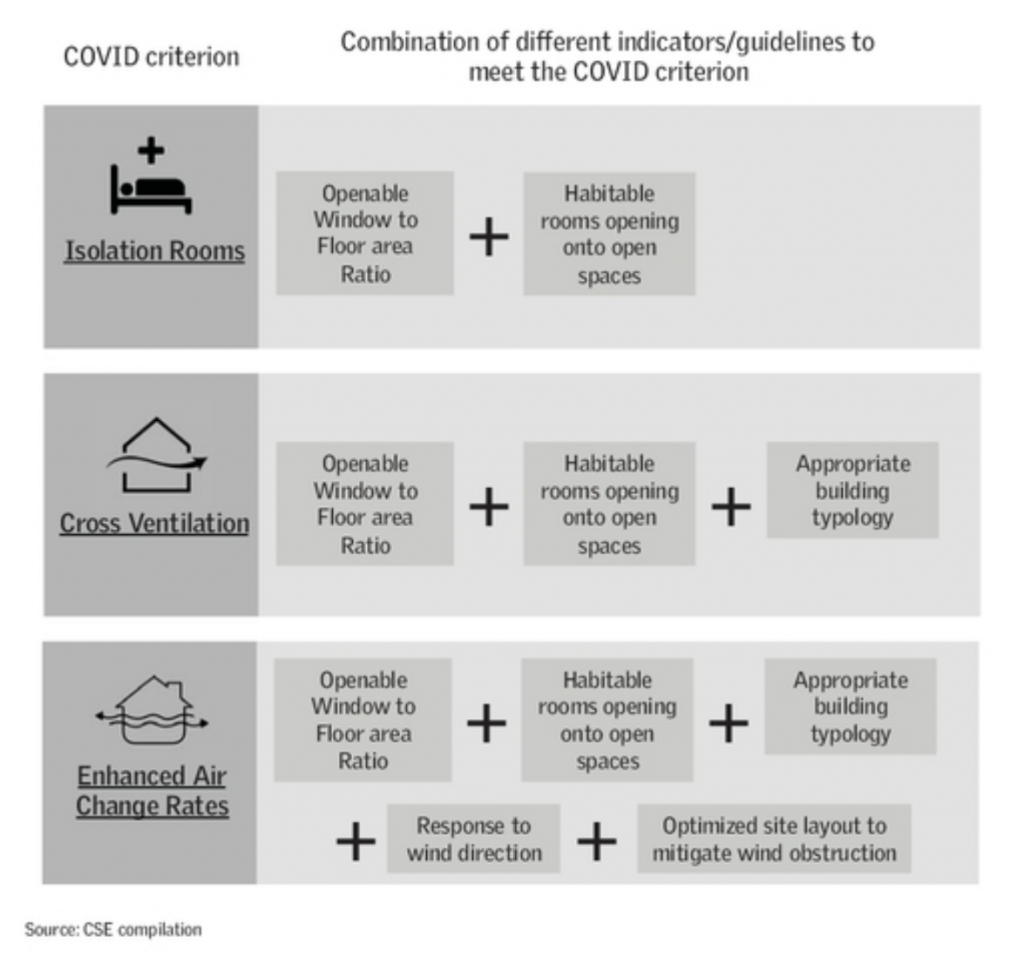

Covid-19 has had a major effect on interiors and architecture. Covid-19 affected the interiors of homes, schools, offices, and much more. Covid-19 has created many interior changes to homes. Due to the quarantine, more and more homes became equipped with home offices and remote learning spaces. Because people started working and doing school from home, home offices, and remote spots are essential (Squier). In homes Covid- 19 affected foyers. People have more knowledge and are aware of maintaining sanitary areas in their homes (Squier). After Covid-19, foyers will be renewed and not only be a place to take off your shoes but may also be a place to wash your hands (Squier). After the Covid-19 quarantine, people go back to school. One new design you will see in schools is the integrity of pods. Pods will be classroom size groups or areas that will be self-contained and isolated (Mortice). Schools will also include modular systems that will be separate from the main school building (Mortice). Many people also go back to work, and the interiors of offices are affected by Covid-19. As a solution to this Dan Kaplan and Sara Davis have created “The Pandemic-Resilient Office Tower”. This office has solutions from the bathrooms to the lobbies on how to decrease the spread of disease. One thing you can expect to see in office buildings is “pinch point-free lobbies” (Kaplan and Davis) Because the center for disease control (CDC) has identified that “limiting close face-to-face contact with others is the best way to reduce the spread of covid-19” the pinch point-free lobby includes a one-way circulation pattern from the entrance with space for health screening prior to entering the rest of the office (Kaplan and Davis). The need for good Ventilation was not only seen after the 1918 flu but was also a need after covid-19. Offices after covid-19 also contain a lot of natural light/windows and enhanced ventilation and filtration. Natural light and windows are in effect because a health crisis can be stressful, but natural light and connection to the outdoors can alleviate stress (Kaplan and Davis). Enhanced ventilation and filtration are not only important to be included but it is important to be seen. Kaplan and Davis don’t only recommend ventilation and filtration but they also say it should be seen, “consider making localized fan-filter air purification visible during periods of increased health risk. This is more psychologically comfortable for occupants, who then will know there is filtration occurring.” (Kaplan and Davis). Windows are not only a solution for offices but are also a solution in homes. Windows in homes create natural ventilation and they are necessary for ventilation and daylight in homes (Parrey). Covid-19 allowed for a lot of suggestions in homes for ventilation through the use of windows. In the chart below you can see what’s recommended.

Conclusion

Past and current pandemics have major effects on the way we design and build domestically and commercially. Past pandemics like cholera and the 1918 flu have shaped our interiors today, imagine our sewage still contaminating our drinking water or the lack of ventilation in homes and buildings. Covid-19 has and will keep affecting our interiors. Each pandemic has left a mark on our interiors and architecture for the best.

Works Cited

Cockrell, David L. “‘A Blessing in Disguise’: The Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and North Carolina’s Medical and Public Health Communities.” The North Carolina Historical Review,vol. 73, 1966.

Johnson Stevens.The Ghost Maps. Riverheadbooks,2006

Kaplan, Dan, and Sara Davis . “The Pandemic-Resilient Office Tower .” CTBUH Journal , no. 4, 2020, pp. 32–39.

Mortice, Zach, et al. “What Will Architecture Design Look like after COVID-19?” Redshift EN, 2 Dec. 2020, https://redshift.autodesk.com/architecture-design-covid-19/.

Ogle, Maureen. “Domestic Reform and American Household Plumbing, 1840-1870.” Winterthur Portfolio, vol. 28, no. 1, 1993, pp. 33–58., https://doi.org/10.1086/496603.

Parrey, Arif Ayaz, editor. “Optimization of Natural Ventilation in Residential Buildings in the Wake of COVID-19.” BREATHABLE INDOORS: CASE FOR PROPERLY VENTILATED SPACES FOR HEALTHY LIVING, Centre for Science and Environment, 2021, pp. 26–28, http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep37913.5. Accessed 2 May 2022.

Planner , Sandy James. “How Do Pandemics Change Housing Unit and Building Design? Lessons from 1918 for Today.” Viewpoint Vancouver, 10 Aug. 2020, https://viewpointvancouver.ca/2020/08/10/how-do-pandemics-change-design-lessons-from-1918-today/.

Sisson, Patrick. “How LA’s Health Craze Birthed Modernist Design.” Curbed LA, Curbed LA, 28 June 2019, https://la.curbed.com/2019/6/28/18693201/lifestyle-health-food-modern-architecture-lovell-house-neutra.

Squier, Anna. “How the Pandemic Is Reshaping Interior Design so Far.” Dwell, 20 Oct. 2020, https://www.dwell.com/article/coronavirus-pandemic-interior-design-impact-0bf0f8a1.

Yuko, Elizabeth. “How Previous Epidemics Impacted Home Design.” Architectural Digest, 31 Mar. 2020, https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/subway-tile-design-in-epidemics.