From 1348 to 1351, Jewish Communities were blamed for their “accused” role in spreading the Black Death across Europe, resulting in the persecution and burning of thousands (Cohn, Jr., 4). The Chinese Community faced mass persecution during an outbreak of the Bubonic plague in San Francisco during the early 20th century. Violence toward homosexual men and women doubled during the AIDS epidemic in New York (Greer, 1986). Currently, America is seeing this same prejudice and racial harassment towards the Asian communities once again with the Covid-19 pandemic. Every pandemic is different. Mutations and genetic makeups are different, their origins are different, but one thing remains constant. When times of uncertainty reach the majority in society, the easiest course of action is to deflect the havoc surrounding them onto the minority, or the underrepresented. One would not dare to say that pandemics bring out the worst in society, however, they might say that pandemics bring out what is wrong with society. The hidden biases and prejudices that hide underneath the majority of members’ conscious facades come to light when that sense of composure and safety the “normal” brings, disappears.

“Pandemics like Covid reveal in the most painful way what we need to fix in the world.”

-Aaron Bernstein, Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment (Milano, 2021)

The problem is not necessarily that pandemics increase prejudice, the problem is the repetitive nature of prejudice. No matter what society, no matter what year, and no matter what disease, a central theme is an underrepresented community seemingly scapegoated due to the ineptitude of governments, or the lack of education from the general public. Society as a whole tends to think that they learn from history, whether through, mistakes, successes, or something in-between. However, the truth is that pandemics reveal that society learns much slower than we assume, possibly not learning at all.

The Black Death

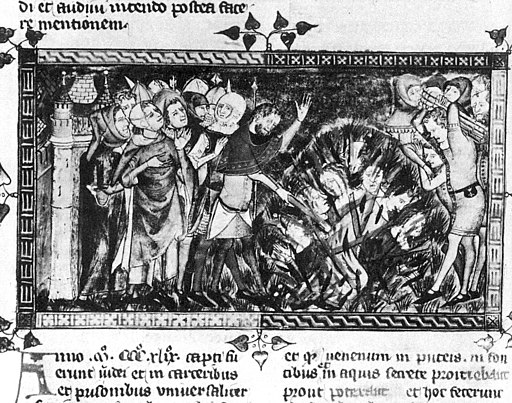

In recent memory, one of the most common minority scapegoats has been the Jewish community. In the 14th century, the Black Death came to Europe, and in four years, killed between 30% and 60% of the European population (Wade, 2020). Amid the havoc, Jewish communities “were accused of poisoning food, wells and streams, tortured into confessions, rounded up in city squares or their synagogues, and exterminated en masse” (Cohn, Jr., 4). In a time where “God’s wrath” was another answer to the pain and misfortune the plague brought onto Europe, it is not out of the ordinary to see violence brought onto those seen as outsiders, or less than what the majority in a society view as the norm. These accusations did not stop at Jewish communities though, as “In the case of accusations of well-poisoning, it was outsiders – Jews, Catalans, foreign beggars or simply the poor – who served as scapegoats.” (Cohn, Jr., 9). In one of the more infamous accounts of Jewish persecution during the time, Jewish communities in Strasbourg, France were gathered and publicly burnt to death. Cohn Jr. noted that “the Jewish community had first to have been sentenced to mass death, and that sentence and its execution came from the top of society: Bishop Berthold’s conference, backed by the military might of the Alsatian nobility.” (Cohn Jr., 18).

The majority in Europe, specifically in Germany, southern France, and Spain, persecuted the minorities present in their society to deflect the misery brought on by the pandemic onto a weaker community (Cohn, Jr., 8). The idea of “deflecting” the misery, or the blame of society as a whole, is such an easy course of action to take for a majority group. However, as the pandemic dissipates, and the need to deflect blame becomes less prevalent, the prejudice once so profound gets suppressed, waiting to peak its ugly head again in the future.

The San Francisco Plague

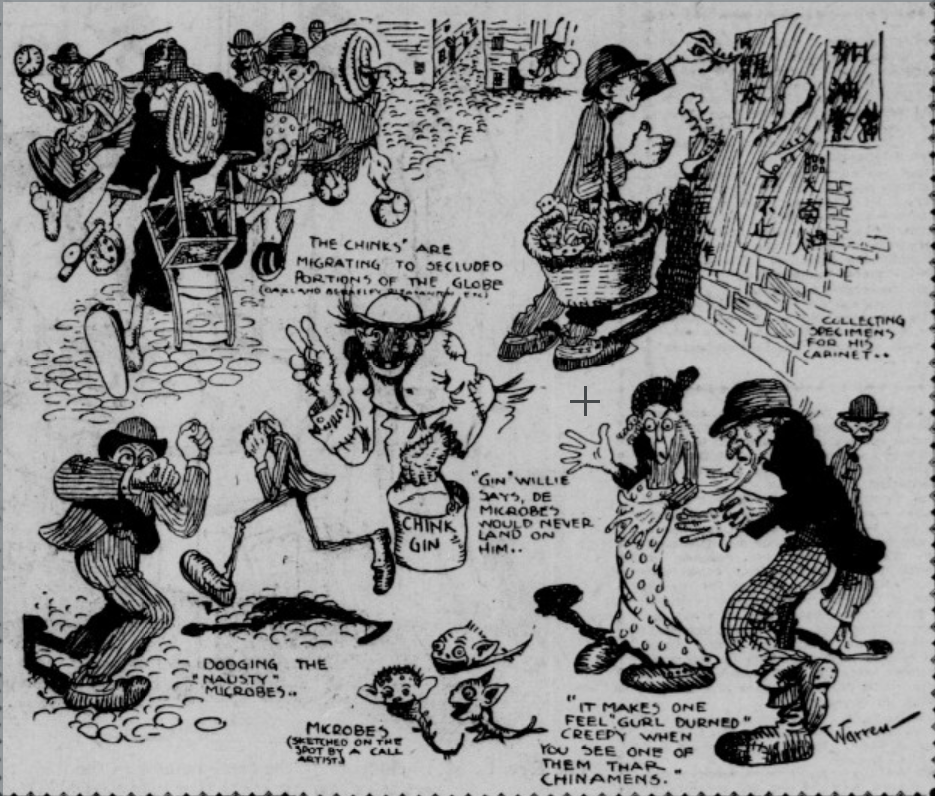

In the early 20th century, San Francisco was confronted with the Bubonic plague. At the center of the blame was the Chinese community. Politicians lied to the rest of the country, anti-Chinese rallies were commonplace among San Francisco citizens, and the Chinese community was scapegoated by politicians, the media, and the white majority in society. In her book, The Barbary Plague: The Black Death in Victorian San Francisco, Marilyn Chase stated, “The Chinese were blamed for the crowding and dilapidation of Chinatown, even though bias barred them from living elsewhere.” (Chase, 11). Their skin color, physical characteristics, and culture set them up for failure after the death of an Asian man early in 1900. This prejudice had been developing for years, with early Chinese immigrants in the 1850s being “considered to be “an inferior race” and a “degraded people.” (Trauner, 70). This culminated in the San Francisco plague, specifically in Chinatown. As the plague broke out, Chinatown was quarantined, “blockading the whole district was discrimination. Anyone could see the quarantine rope markedly zigzagged to exclude white stores on the boundaries of Chinatown.” (Chase, 20). The leaders in San Francisco had two main incentives: political and economic. In San Francisco, scapegoating the Chinese community was an easy fix to deflect responsibility for the outbreak. However, as news leaked of a possible Bubonic plague outbreak, the goal of these leaders was to hide the severity of the pandemic, and to promote San Francisco as a clean, and relatively safe, city for economic gain.

This prejudice was only heightened by racist media portrayals of the Chinese community, and the pre-pandemic existence of prejudice towards the Chinese community. In 1897 in San Francisco, an anti-Chinese rally, where “About fifteen hundred or two thousand people, a large number of whom were ladies attended the First Ward anti-Chinese meeting.” (San Jose Mercury-news, Volume XXXI, Number 152, 23 June 1887). In this rally, Judge Reynolds, the leader of the courthouse, stated that “It is not a question of race prejudice. It is a prejudice against a fact – against a town of slaves within a town of free men.” (San Jose Mercury-news, Volume XXXI, Number 152, 23 June 1887). When pairing the existing prejudice with a deadly pandemic associated with that minority group only a couple of years later, the outcome speaks for itself. The prejudice that the Chinese community faced remains a central theme today in the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic. If the answer to havoc remains unfound, the problematic response will remain the same.

The AIDS Epidemic

The AIDS epidemic is one of the most notable, and socially defining pandemics of the 20th century. Even with social norms changing in society today, the LGBTQ+ community will always be viewed as an outsider. In the 1980s, HIV/AIDS hit America hard. Doctors in major East and West coast cities began seeing spikes in rare forms of infections and cancers. Two groups were hit hardest by the disease: homosexuals and intravenous drug users. Due to this, the CDC “Initially (and unfortunately)… labeled it GRID (gay-related immunodeficiency disease)” (McMillen, 104). The CDC later renamed it AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome), however, the damage was already done, bringing the first of many mistakes from government officials. With society under the impression that the source of HIV/AIDS was the homosexual community, violence towards the homosexual community drastically increased. In a 1986 article from the New York Times, journalist William R. Greer reported that “New York cases (violence towards homosexual men and women) said to double.” (Greer, 1986). In one specific occurrence, Matthew Holloway, a homosexual man who witnessed his roommate being assaulted in San Francisco, stated that his assailants shouted, “We should kill you first because you’re gonna give us AIDS” (Greer, 1986). He was attacked by a group of young people, with gang attacks being the most common form of violence against the homosexual community. The stigma toward homosexual men and women only continued to grow, as the AIDS epidemic continued to move through the country. As sociologist Philip H. Pollock III has noted, when talking about the social construction in perspective, Pollock III states that “when an issue gets tied to an identifiable group, people can reference their effect toward that group as a shorthand for figuring out the issue.” (Pollock III, et. al., 1993). This stigma from majority groups fueled the AIDS epidemic, making it even more difficult for the homosexual community to integrate into society.

The Covid-19 Pandemic

Roughly 120 years after the San Francisco Plague, where Chinese communities faced unfathomable amounts of prejudice and racism, America is experiencing a worldwide pandemic, with the same prejudice. With the COVID-19 pandemic originating in China, the majority of the blame has come upon the Chinese immigrant community and those with Asian heritage. Dr. Sumie Okazaki, a Professor of Applied Psychology at NYU, noted that “there has been an alarming rise of xenophobic backlash and racial harassment and violence against Asians globally, blaming China and the Chinese for the spread of the COVID-19 virus.” (Okazaki, NYU). This racial harassment and violence are being labeled ‘hate crimes, and they are not limited to the Chinese community. Thai immigrants have also been a major target of these assaults.

According to the group ‘Stop AAPI Hate’, they say that they have “received more than 2,800 reports of hate incidents directed at Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders nationwide last year.” (BBC, 2021). The majority of these assaults are verbal harassment, with 70.9% of Asian-Americans incidents being verbal (BBC, 2021). The stigma toward the Asian-American community is only continuing to grow, as in addition to the fear of violence, opportunities, and refusal of service have come into play as well, with 8% of all hate crimes being workplace discrimination or refusal of service (BBC, 2021).

In Conclusion

America has long dealt with discrimination. Since its birth, American discrimination, prejudice, and racism have remained a central theme in American society and culture. As America has advanced in society, this prejudice and racism have been suppressed more than ever before, but one cannot say that it does not exist. In the midst of one of the most deadly pandemics in human history, Asian-American hate skyrocketed, revealing that society has not learned from its previous wrongdoings. As a society, America is in a state of chaos, not because of the pandemic, but due to the prejudice these underrepresented communities still face. The fact of the matter is, that minorities will always struggle because majorities will always exist.

Citations

BBC.com. “Covid ‘Hate Crimes’ against Asian Americans on Rise.” BBC News, BBC, 21 May 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-56218684.

Chase, Marilyn. The Barbary Plague: The Black Death in Victorian San Francisco. Random House, 2004.

Cohn, Samuel K. “The Black Death and the Burning of Jews.” Past & Present, no. 196, 2007, pp. 3–36, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25096679. Accessed 25 Apr. 2022.

Greer, William R. “Violence against Homosexuals Rising, Groups Seeking Wider Protection Say.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 23 Nov. 1986, https://www.nytimes.com/1986/11/23/us/violence-against-homosexuals-rising-groups-seeking-wider-protection-say.html.

Halkitis, Perry N. “Discrimination and Homophobia Fuel the HIV Epidemic in Gay and Bisexual Men.” American Psychological Association, American Psychological Association, https://www.apa.org/pi/aids/resources/exchange/2012/04/discrimination-homophobia.

McMillen, Christian W. Pandemics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2016.

Milano, Brett. “With Covid Spread, ‘Racism – Not Race – Is the Risk Factor’.” Harvard Gazette, Harvard Gazette, 23 Apr. 2021, https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2021/04/with-covid-spread-racism-not-race-is-the-risk-factor/.

Okazaki, Sumie. “Asian American Experiences of Racism during COVID-19.” Steinhardt.nyu.edu, 7 June 2020, https://steinhardt.nyu.edu/ihdsc/on-the-ground/asian-american-experiences-racism-during-covid-19.

POLLOCK, Philip H., et al. “On the Nature and Dynamics of Social Construction: The Case of AIDS.” Social Science Quarterly, vol. 74, no. 1, 1993, pp. 123–35, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42863166. Accessed 25 Apr. 2022.

San Jose Mercury-news, Volume XXXI, Number 152, 23 June 1887

Trauner, Joan B. “The Chinese as Medical Scapegoats in San Francisco, 1870-1905.” California History, vol. 57, no. 1, 1978, pp. 70–87, https://doi.org/10.2307/25157817. Accessed 25 Apr. 2022.

Wade, Lizzie. “From Black Death to Fatal Flu, Past Pandemics Show Why People on the Margins Suffer Most.” Science, 14 May 2020, https://www.science.org/content/article/black-death-fatal-flu-past-pandemics-show-why-people-margins-suffer-most.