During difficult times, people become desperate, and are willing to do whatever it takes to survive. An example of this happening is the hoarding and price gouging of essential items at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. This is hardly the first time this has happened, and there are reasons why people go to price gouging as a way to get by. When does the price of something go from adjusting for inflation or supply and demand to price gouging? According to Matt Zwolinski, the director of the economics undergraduate program at the University of San Diego, there are three elements that usually cause price gouging. A disaster of some sort has occurred; there are necessary items with limited stock in the area; and people are able to set prices as high as they want (Zwolinski 4). Many states today have price gouging laws to try and prevent it from happening during these emergencies, but it doesn’t always work, as you will read throughout this article.

Laws of Price Gouging

Price gouging, which is buying an item and then re-selling it at a much higher price, or raising the price of something you are selling to an unacceptable amount, is usually attributed to disasters as that is when people are the most susceptible to it. 38 states have anti-price gouging laws, while 12 do not (Davis 6-7). However, in cases like the gasoline prices after hurricane Irma in the impacted areas, people will find loopholes to get out of complying with anti price gouging laws, as you will read below.

Examples of Price Gouging

Cholera during the Gold Rush

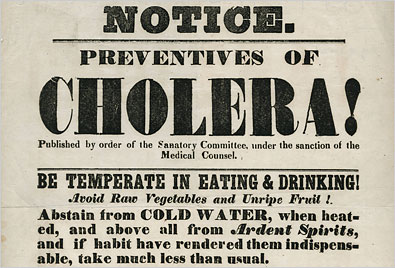

During the Gold Rush in San Francisco, an outbreak of cholera made doctors in the area drive up their prices (Roth 10). The outbreak coincided with the Gold Rush and was spread all around the early United States (Roth 1). The outbreak was first started in New Orleans, but the impact of cholera in the cities of Sacramento and San Francisco during the Gold Rush is rarely talked about. One doctor admitted to charging $15 a day for his visits, using wages of $16 a day as proof that he should be allowed to raise his price for his visits (Roth 10). The normal price for a visit during this time in Los Angeles would be somewhere around $5-$10 depending on the timing and what was done (Barrows 1). This made many people go without medical care so they wouldn’t have to pay for the exorbitant fee. The knowledge of doctor’s in the era did not match their rates. As the poster below shows, doctors in 1832 believed that immoral behavior, such as eating more than necessary, made you more susceptible to cholera. This was still the prevailing view in 1850. Both of these issues fueled the fire of the epidemic and allowed for the disease to spread freely throughout early America.

Image Source

1918 Spanish Flu Price Gouging

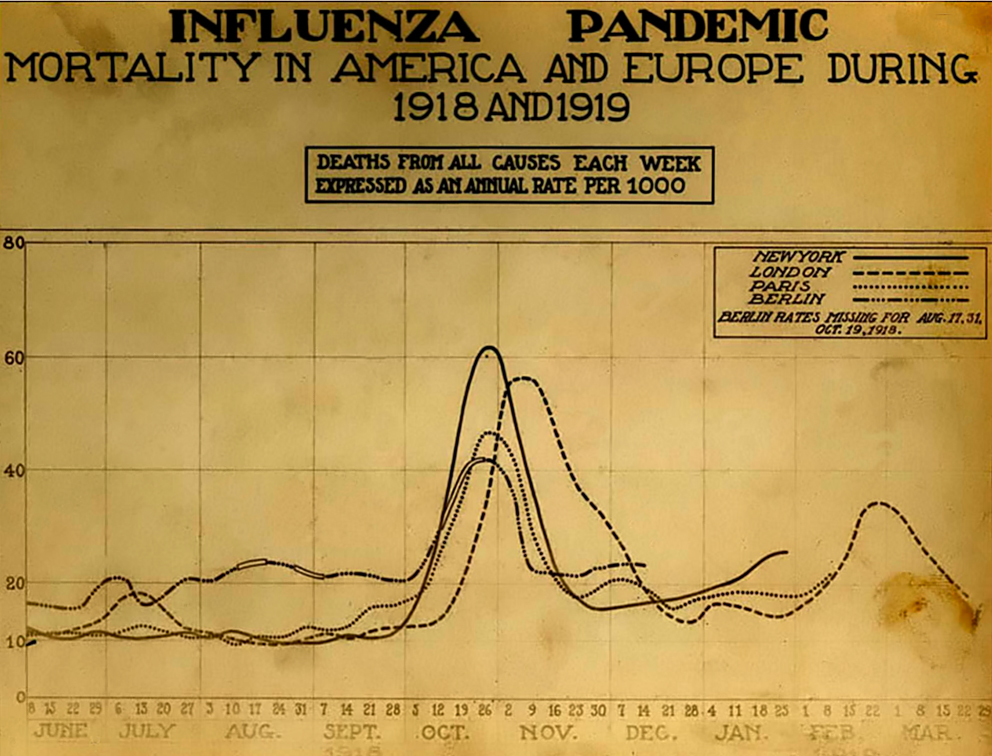

During the Spanish flu pandemic, the US and other countries struggled with the death toll that the Spanish flu was leaving in its wake. Mortuaries and cemeteries were strained by the rapid accumulation of victims (Schoch-Spana 1). People in the US felt that funeral homes and cemeteries weren’t doing enough to help the struggling communities, and some were accused of price gouging. In Philadelphia, graveyards were becoming extreme with their pricing as explained here, “Some graveyards raised the price of burial to fifteen dollars, even if the family themselves buried the body.” (Stetler 15). When city officials discovered this, the price was set to $9 per burial, and $15 if cemetery employees dug the grave (Stetler 15).

2004 Influenza Pandemic Price Gouging

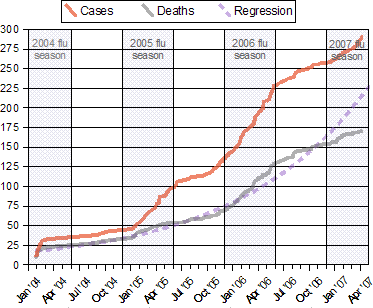

One of the more recent pandemics was an outbreak of H5N1, otherwise known as influenza, in 2004. There was a shortage of how much vaccine was being produced, so countries and people were buying the vaccine for way above market value. The distributors of the vaccine who were able to make it saw the demand and raised the price, and at least two states responded with lawsuits against them (Lister 14).

Image Source

2017 Hurricane Irma Price Gouging

Price gouging is not limited to disease related disasters either. Before, during, and after hurricane Irma made landfall and devastated areas of Florida and Georgia, gasoline prices increased and stabilized at a higher rate before the emergency declaration was put in place, which triggers the states’ price gouging laws. This created a loophole to the law as they were able to charge a higher price for gas despite the anti-price gouging laws that were in place (Wright 1).

Image Source

2020 Covid-19 Pandemic Price Gouging

Price gouging changed slightly in 2020, as almost all shopping during the pandemic is done online. Price gouging is a lot easier and is harder to detect online, but some retailers have been able to spot price gouging and remove those items from their sites. The New York Times put out an article about a man who bought thousands of bottles of hand-sanitizers and anti-bacterial wipes, and was re-selling them for $8-$70 (Nicas 1). To try and prevent this kind of price gouging online, Amazon stated they created a dedicated team to monitor and take down price gouging on items that were essential to health during the pandemic, such as masks and hand sanitizers. Amazon came out in early March reported this, ” …Amazon removed $30,000 offers from the marketplace and suspended more than 2,500 seller accounts in its US marketplace for violating its price-gouging policies” (Singh 2). Another issue with the pandemic is the shortage of PPE. N-95 masks prices skyrocketed as companies tried to outbid each other in an attempt to secure the masks for themselves (Clark 1). Earlier in the same article written by Clark the reporter mentions hiding the masks in a food truck, so that the truck would not be appropriated by equally desperate federal agencies. This desperation is what fuels most price gougers to take action and profit off of these disastrous situations.

Conclusion

People are willing to do whatever it takes to get an edge in life. Whether it is price gouging with medical supplies, raising the price of gas, or giving burials exorbitant fees, people always try to make the most out of a bad situation. This is why so many states have adopted anti price gouging laws, and the reason that the executive order was placed to stop the hoarding of medical resources in 2020. As despite our selfish natures, we should still try and work for the good of everyone, not just ourselves.

Works Cited

Kress, George and Walter Lindley. “A History of the Medical Profession of Southern California” University of California, 1910. https://babel.hathitrust.org

Stetler, Christina M. “The 1918 Spanish Influenza: Three Months of Horror in Philadelphia.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, vol. 84, no. 4, 2017, pp. 462–487. JSTOR, https://pa-history.org

Monica Schoch-Spana, “Implications of Pandemic Influenza for Bioterrorism Response”, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Vol 31, no. 6, 2000, pp.1409–1413, https://doi.org/10.1086/317493

Lister, Sarah. “Influenza Vaccine Shortages and Implications” CRS Report for Congress, 2004. 2004 price gouging during influenza vaccine shortage

Wright, J. T., Placid, R. L., & Allen, M. T. “Price Gouging In A Hurricane: Do Free Market Forces Circumvent Price Controls?”. Journal of Business & Economics Research (JBER), 2019, vol. 16(2), pp. 19-30. https://doi.org/10.19030/jber.v16i2.10319

Singh, Spandana, and Koustubh “K.J.” Bagchi. “How Internet Platforms Are Combating Disinformation and Misinformation in the Age of COVID-19”. Amazon, New America, 2020, pp. 6–7. www.jstor.org/stable/resrep25418.4

Nicas, Jack. “He Has 17,700 Bottles of Hand Sanitizer and Nowhere to Sell Them”. New York Times, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com

Clark, Doug. “Inside the Chaotic, Cutthroat, Gray Market For N95 Masks”. New York Times, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com

Zwolnski, Matt. “The Ethics of Price Gouging”. Business Ethics Quarterly, Vol. 18, No. 3, pp. 347-378, July 2008. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1099567

United States, Executive Office of The President [Donald Trump]. Executive Order 13910: Preventing Hoarding of Health and Medical Resources To Respond to the Spread of COVID–19. 23 March 2020. Federal Register no. 2020-06478, pp. 17001-17002. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-03-26/pdf/2020-06478.pdf

Davis, Cale Wren. “AN ANALYSIS OF THE ENACTMENT OF ANTI-PRICE GOUGING LAWS”. Montana State University, 2008. https://scholarworks.montana.edu