It has been a little over a year since the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, which has wreaked havoc on our lives ever since. From how we work, vote in elections, and even see family and friends, our daily lives have adapted to these new circumstances. However, with vaccines now available to most of the population, the end of this challenging chapter in recent history seems to be more and more tangible. With the end in sight, people are now beginning to wonder what effects will persist in our society after COVID’s decline. Every possible consequence resulting from this pandemic cannot be listed in its entirety since the list will be too long. Instead, looking at a single category of life can make listing the effects easier and more manageable. What social effects will COVID-19 have?

Because this pandemic is still actively happening, it is hard to tell what the exact social repercussions will be. However, with the benefit of history, we can look back at a past pandemic that is the most epidemiologically like COVID-19 and prevalent in our nation’s history: the 1918 flu.

America’s Forgotten Pandemic and the Social Effects Left Behind

“The reported epidemic is not regarded here as having serious proportions”—this mindset made up the consensus around the outbreak of influenza in 1918 (New York Times, 28 Jun. 1918). The Spanish flu, also known as the 1918 influenza pandemic, is often regarded as “America’s forgotten pandemic” for a straightforward reason: history does not account for it like it does other historical pandemics. Despite this, the social effects that the 1918 flu did leave behind were genuine for the people who lived through it.

1918, despite having a pandemic named after it, is often remembered in history as the final year of World War I. A war known for being the first global-wide conflict, World War I occupied many people’s minds, from those in government, to soldiers on the field, and to the loved ones they left behind at home. Even if an individual had no connection to the war effort, there is no denying that this significant world event encapsulated most. The United States needed to focus on the war efforts, which did take away eyes from what would become known as the worst influenza outbreak in history (Crosby 21). However, the blatant disregard for the flu was very much noticed by the general public when the waves started to hit; how was it possible that those in power with the responsibility of protecting America were turning their heads from an illness that was wiping out droves of people? Although the war was happening and was the center of attention, mistrust grew amongst the American people towards the government due to the underplaying of the flu (Aassave). “People lost faith in everything,” author John M. Barry states. “In their government, in what they were being told, in each other. It just isolated people even further. If trust collapses, then it becomes everyone for themselves, and that’s the worst instinct in a crisis of this scale” (Illing). The lack of worry that the US government exhibited at the beginning of the 1918 influenza pandemic did nothing but make the people lose trust, as it was clear that this strain of flu was not something that could be ignored.

The individuals that the public look to for guidance on spreading diseases, such as medical personnel, were left defenseless to the Spanish flu. Unlike most significant diseases before this outbreak, the Spanish flu plagued both those in the prime of life (aged 20-40) and the elderly (65+ years old). It killed about 675,000 in the United States out of a predicted 500 million cases worldwide (CDC). Doctors across the country became swamped with patients inflicted with influenza, with such intensity that they could not keep up. Nurses began seeing 20-30 cases each day, with some even seeing 40 cases a day (“Calm, Cool, Courageous: Nursing and the 1918 Influenza Pandemic”). The number of sick individuals quickly outnumbered the staff at many hospitals around the United States, which left the medical community essentially begging for volunteers to help in the fight against influenza (CDC). This strain of the flu killed many and killed them quickly, making healthcare workers feel powerless in the battle to combat it. “I am not going into the history of the influenza pandemic,” says Dr. Victor Vaughan, a doctor during the time of the outbreak in his novel written years after the pandemic’s end. “It encircled the world, visited the remotest corners, taking toll of the most robust, sparing neither soldier nor civilian, and flaunting its red flag in the face of science” (Vaughan 432). Dr. Vaughan’s hesitancy to speak out about the outbreak is a prime example of the toll it left on the medical professionals at the time; they were battling an illness of such high proportions that they felt helpless in the fight against it.

In short, America moved on from this chapter swiftly rather than confront the pain that this pandemic caused. While there is a shortage of personal accounts written by the people who experienced this pandemic, this does not negate the suffering that influenza caused to those who survived. In one of the very few pieces of literature about the Spanish flu, Pale Horse, Pale Rider, the pain of those who had survived the pandemic is perfectly summarized: “the body is a curious monster, no place to live in, how could anyone feel at home there? … The human faces around [Miranda] seemed dulled and tired, with no radiance of skin and eyes as Miranda remembered radiance” (Porter 257). With its high death toll, the pandemic left a haunting mark on the lives of the people who lived through it. Historical demographer Svenn-Erik Mamelund researched the Spanish flu’s effect on mental health and found that “the number of first-time hospitalized patients with mental disorders attributed to influenza increased by an average annual factor of 7.2 in the six years following the pandemic” (Eghigian). Mamelund also found that survivors of the Spanish flu showed signs of depression, sleep disturbance, and dizziness; there was also a positive correlation between influenza deaths and suicides in the United States (Eghigian). In summary, mental health suffered due to the Spanish flu and the changes it forced on the people.

When looking at the mortality rate in the second and third waves of the 1918 flu in the United States, statistics showed that “a disproportionate number of foreign-born had died in the fall wave,” which reveals that influenza unequally affected minority groups (Crosby 99). While there is debate amongst historians as to why the 1918 flu affected minority groups at a higher rate, the reality of this notion was very much visible as the pandemic raged on in the United States. At the time of this influenza outbreak, African Americans faced restricting factors concerning their access to healthcare. Racist theories of African Americans being biologically inferior to white people, not having the best access to hospitals, and already poorer health status made the outbreak of influenza much more challenging to process and overcome (Gamble). African Americans, as a whole, succumbed to diseases at higher rates than their white counterparts in various outbreaks before the flu; history blames this on the factors stated earlier (Gamble). Hospitals often turned away African Americans who had come down with the flu and African American nurses who wanted to help in taking care of the sick (Blackburn). These instances led to the inception of several all-black Red Cross chapters; these chapters would run under African American nurses, who would take care of African Americans who had been turned away from predominantly white healthcare facilities (Blackburn). The effect that this inequality left is simple: things remained the same. Meaning, minority groups remained overlooked; specifically, African Americans continued to suffer at the hands of the racist ideologies at the time.

African American flu nurses, 1919

Looking Ahead: What Social Effects will COVID-19 Leave Behind?

Researchers will likely not study the effects of COVID-19 on the social aspect of life until many years after the pandemic ceases. However, by reflecting on the 1918 influenza pandemic and speaking with individuals currently living through this pandemic, we can make many predictions about what social effects will persist after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although President Donald Trump had received information in January 2020 on a virus in China that had the potential to “spread globally,” the United States did not take complete federal actions to prevent the spread until March (Myers). This fact, which became known months after the pandemic had commenced, leads to a consequence that has started to take shape: mistrust in the government (Myers). The actions of Trump’s administration during COVID’s onset led to falls in overall public opinion against Trump as a president and the government overall. In a Pew Research Center survey of 9,920 Americans, 57% said the comments made by Trump regarding the pandemic had been wrong and untrustworthy, as well as roughly 60% saying the entire administration hardly ever spread accurate information about the pandemic (Jurkowitz). Trump’s comments on COVID in his press conferences and online sparked controversy and confusion amongst Americans. Statements like COVID being a “flu,” suggesting disinfectants as treatments for COVID inflections, and that COVID would “disappear” on its own led to a mass misunderstanding of COVID and loss of trust of many Americans (“Timeline of Trump’s Coronavirus Responses). Wherever your personal political beliefs fall, the effect of Trump’s COVID response can be seen in the fall of America’s overall trust in the government; this shows the president’s influence and the impact of their remarks during times of crisis.

Trump administration meeting with COVID survivors, 2020

Much like observed in the Spanish flu, medical professionals during COVID have become incredibly overwhelmed with patients at alarming rates. The Physicians Foundation conducted a survey of 2,334 physicians at the forefront of the COVID pandemic regarding their wellbeing and found the following: 30% reported feeling a sense of hopelessness in regards to their capability of slowing the pandemic, 18% admitted to using substances (medications, illicit drugs, or alcohol) to cope with the pressure of their practice, as well as 22% reported knowing a physician who committed suicide as a result of the stress that the pandemic caused (“The Physicians Foundation 2020 Physician Survey: Part 2”). The mental strain that medical professionals have had to endure to help combat the coronavirus is real and shows an impact likely to last after COVID is gone. In an MDLinx survey amongst 1,251 healthcare professionals, 48% reported that the COVID pandemic has caused them to seriously reconsider their career choice/practice (Murphy). This statistic is incredibly daunting to consider; while this survey only concerns the opinions of just over 1,000 healthcare workers, to know that almost half of them are having doubts about their career paths because of the stress they are experiencing should raise serious concerns. Will this lead to a decrease in healthcare professionals in the future?

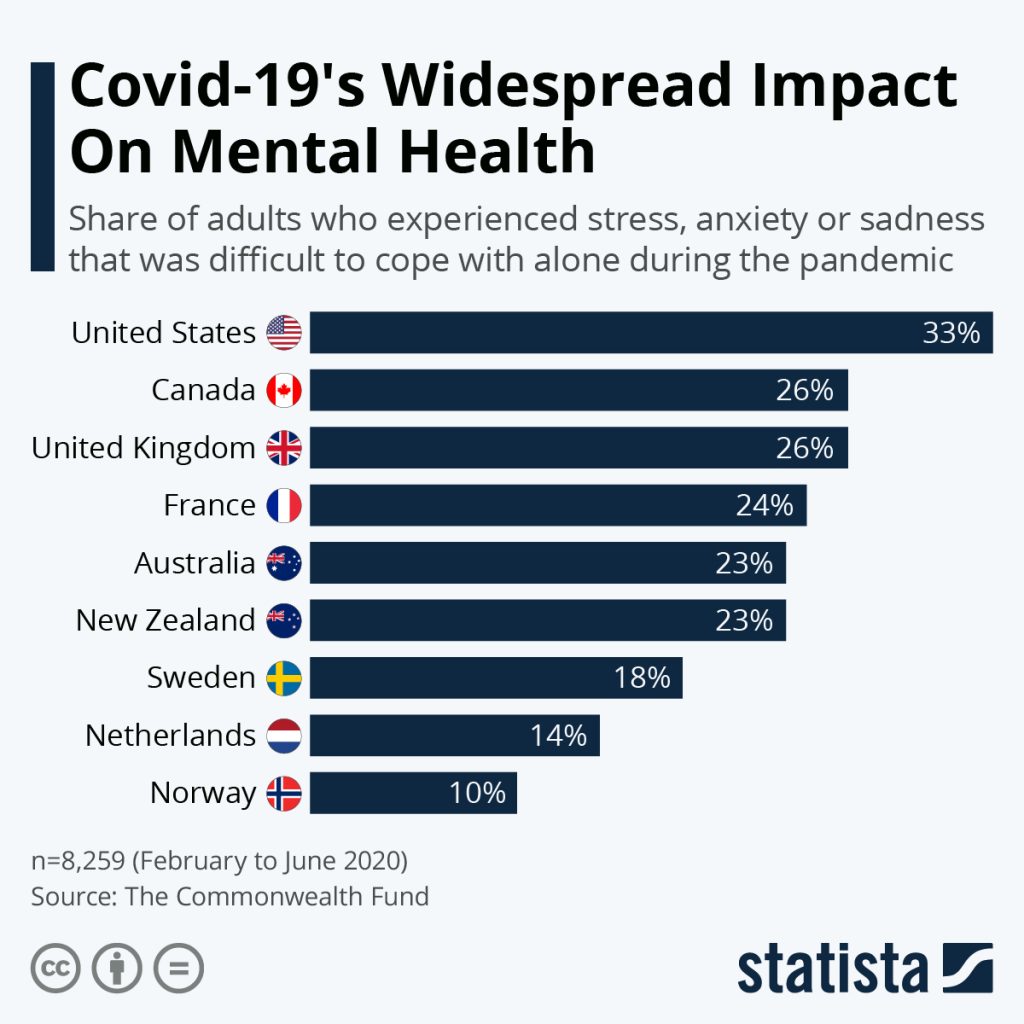

As observed in the 1918 influenza pandemic, a significant prediction for a social consequence of COVID is the changes in mental health in the people living through it. In various surveys given by the Pew Research Center in 2020, 9,920 Americans gave insight into how their lives changed throughout COVID-19. The statistics were as followed: 28% reported that they believed their physical or mental health had been negatively affected, 41% reported feelings of isolation from missing social interaction, and 45% of those 65+ years old and 27% of people under 50 thought that they became unable to partake in the pleasures of their daily lives from before the pandemic (Kessel). The Household Pulse Survey, which is conducted by the Census Bureau to understand the impacts of the pandemic, found that 4 in 10 adults said they felt symptoms that align with depression and anxiety disorders; this shows an increase from results of a 2019 survey where only 1 in 10 adults reported these symptoms (Kamal). While these statistics only provide insight into people’s current feelings and mental states during COVID-19, this does paint a telling picture: will these feelings of isolation and dissatisfaction with life lead to mental health problems in the long run? It can be seen during the Spanish flu that these feelings existed in the people who lived through it and that many still felt like they were suffering after the flu had died down. It would not be a surprise to find out in the future that mental health on a global scale was affected by COVID-19.

Data provided by Statista on the percentage of adults who dealt with distress in relation to the pandemic, 2020

Former President Donald Trump, on the record, called COVID-19 the “Chinese virus” due to its origins in Wuhan, China. Mike Pompeo, former Secretary of State under the Trump administration, referred to COVID-19 as the ‘Wuhan virus” for the same reason of it being discovered in Wuhan, China. This blatantly racist language reflects many prior issues in our country, as well as another consequence of COVID-19: social inequality and racism. Racially motivated attacks against Asian descent have become far too familiar due to the generalization that all Asians are responsible for COVID-19, which has manifested in verbal and physical attacks against Asian Americans. STOP AAPI HATE, a coalition created by numerous Asian American groups during the onset of COVID, reported receiving over 1,500 reports of racially-motivated attacks against Asian Americans by April 2020 (“Covid-19 Fueling Anti-Asian Racism and Xenophobia Worldwide”). African Americans have also become plagued by COVID-19 at high rates since many find themselves in essential occupations, such as healthcare workers, grocery store workers, and transit operators. Because about 70% of African Americans report not having a college degree and, thus, cannot find jobs that can take place from home, they stay in these critical positions and are more likely to expose themselves to COVID-19 (Roberts). Reports of racial profiling have become an issue, as the CDC’s implementation of wearing a cloth face-covering in public included bandanas; this did not account for the implications of gang affiliation (Roberts). Many African American men reported having experienced racial profiling while wearing surgical masks or expressed psychological distress because of the fear of being profiled by police during the pandemic (Roberts). Among many more that are likely not reported, these instances show that a regrettable consequence of a pandemic is that it highlights social inequality.

In Summary, What Social Effects Do Pandemics Have?

The question remains: what will the social effects of COVID-19 include? As stated previously, we likely will not know the answer to this question until years after COVID’s end. We can make predictions based on current circumstances, which is easy when you compare the social effects of a past pandemic to what is happening now.

Even though the Spanish flu has the title of “America’s forgotten pandemic,” this does not mean that there were not social effects that arose. The people’s distrust in the government, loss of hope from medical professionals, deteriorating mental health issues that persisted after the Spanish flu’s end, and social inequality and racism were all born out of the pandemic. People’s lives changed after the flu, which helps to understand better why the 1918 influenza pandemic slips into oblivion in history books; it was simply a sore subject to the people who lived through it. This quickness to move on provides context for how the United States could go from a war-torn and pandemic-stricken country to a roaring and innovative place in the 1920s. Perhaps one reason why the Roaring 20’s commenced so soon was that the people wanted to focus on something new, something better.

Reflecting on the Spanish flu allows us to have some perspective on the social effects we will soon face once COVID subsides. Many of the issues that Americans faced during a pandemic over 100 years ago are the same ones we saw in 2020 and continue to see in 2021; how can we trust our government if it is not telling us the correct information about a spreading disease? How are the doctors and nurses at the forefront of this medical crisis handling the stress that they face? How are we going to be affected mentally once the pandemic is over? And, how does a pandemic emphasize the existing social inequalities in our society? While we cannot look to the Spanish flu for a total prediction of what will happen after COVID, as the circumstances of the world in 1919 and 2021 are so different, the social effects of the Spanish flu give us an idea of what could happen. Perhaps, looking at the impact of the Spanish flu will somewhat let us prepare for these outcomes; we could even learn from the Spanish flu and reflect on what we could change to make our world a better place after COVID is gone.

We cannot treat our way out of these problems. We are never going to build enough medical services. Preventing suffering before it happens is the long-term answer for our country. Our goal is to create a community where everybody has the opportunity to thrive.

Kelly Kelleher, M.D.

—

Works Cited

“1918 Pandemic (H1N1 Virus).” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 20 Mar. 2019, www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html.

Aassve, Arnstein, et al. “Pandemics and Social Capital.” VOX, CEPR Policy Portal, voxeu.org/article/pandemics-and-social-capital.

Berg, Sara. “4 Ways COVID-19 Is Causing Moral Distress among Physicians.” American Medical Association, American Medical Association, 18 June 2020, www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/4-ways-covid-19-causing-moral-distress-among-physicians.

Blackburn, Piper H. “How Racism Shaped the Public Health Response to the 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic.” The COVID19 Analyzer, Northwestern University, 3 May 2020, nationalsecurityzone.medill.northwestern.edu/covidanalyzer/news/how-racism-colored-the-public-health-response-to-the-1918-spanish-flu-pandemic/.

“Calm, Cool, Courageous: Nursing and the 1918 Influenza Pandemic.” Calm, Cool, Courageous: Nursing and the 1918 Influenza Pandemic • Bates Center • Penn Nursing, Penn University, www.nursing.upenn.edu/history/publications/calm-cool-courageous/.

“Covid-19 Fueling Anti-Asian Racism and Xenophobia Worldwide.” Human Rights Watch, 28 Oct. 2020, www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/12/covid-19-fueling-anti-asian-racism-and-xenophobia-worldwide.

Crosby, Alfred W. America’s Forgotten Pandemic. 1989.

“How Pandemics Shape Society.” The Hub, 9 Apr. 2020, hub.jhu.edu/2020/04/09/alexandre-white-how-pandemics-shape-society/.

Illing, Sean. “The Most Important Lesson of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic: Tell the Damn Truth.” Vox, Vox, 20 Mar. 2020, www.vox.com/coronavirus-covid19/2020/3/20/21184887/coronavirus-covid-19-spanish-flu-pandemic-john-barry.

Jurkowitz, Mark. “Majority of Americans Disapprove of Trump’s COVID-19 Messaging, Though Large Partisan Gaps Persist.” Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, 16 Sept. 2020, www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/09/15/majority-of-americans-disapprove-of-trumps-covid-19-messaging-though-large-partisan-gaps-persist/.

Kamal, Rabah, et al. “The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use.” Kaiser Family Foundation, Kaiser Family Foundation, 10 Feb. 2021, www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/.

Kessel, Patrick van, et al. “How the COVID-19 Pandemic Has Changed Americans’ Personal Lives.” Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, 8 Mar. 2021, www.pewresearch.org/2021/03/05/in-their-own-words-americans-describe-the-struggles-and-silver-linings-of-the-covid-19-pandemic/.

Maas, Steve. “Social and Economic Impacts of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic.” NBER, May 2020, www.nber.org/digest/may20/social-and-economic-impacts-1918-influenza-epidemic.

Madhav, Nita. “Pandemics: Risks, Impacts, and Mitigation.” Disease Control Priorities: Improving Health and Reducing Poverty. 3rd Edition., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 27 Nov. 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525302/.

Murphy, John. “Nearly Half of Doctors Are Rethinking Their Careers, Finds COVID-19 Survey.” MDLinx, 6 Nov. 2020, www.mdlinx.com/article/nearly-half-of-doctors-are-rethinking-their-careers-finds-covid-19-survey/32iphKz3vp3DlR3LuXOBkA.

Porter, Katherine. Pale Horse, Pale Rider. Harcourt Publishers Group, 1990.

“The Physicians Foundation 2020 Physician Survey: Part 2.” The Physicians Foundation, The Physicians Foundation, 18 Sept. 2020, physiciansfoundation.org/physician-and-patient-surveys/the-physicians-foundation-2020-physician-survey-part-2/.

Roberts, Jennifer D, and Shadi O Tehrani. “Environments, Behaviors, and Inequalities: Reflecting on the Impacts of the Influenza and Coronavirus Pandemics in the United States.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, MDPI, 22 June 2020, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7345270/.

Special to The New York Times. “NO INFLUENZA IN OUR ARMY.: WASHINGTON HAS HAD NO REPORTS ABOUT GERMAN FORCES.” New York Times (1857-1922), Jun 28, 1918, pp. 2. ProQuest, http://unh-proxy01.newhaven.edu:2048/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.unh-proxy01.newhaven.edu/historical-newspapers/no-influenza-our-army/docview/100210342/se-2?accountid=8117

“Timeline of Trump’s Coronavirus Responses.” Congressman Lloyd Doggett, 6 Apr. 2021, doggett.house.gov/media-center/blog-posts/timeline-trump-s-coronavirus-responses.

Vaughan, Victor. A Doctor’s Memories. The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1926. Wallach, Philip A, and Justus Myers. “The Federal Government’s Coronavirus Actions and Failures.” Brookings, Brookings, 1 Apr. 2020, www.brookings.edu/research/the-federal-governments-coronavirus-actions-and-failures-timeline-and-themes/.

Sources for images are embedded in each photo.