Is Mr. Heathcliff a man? If so, is he mad? And if not, is he a devil?

Brontë 222

Introduction

Much can be discerned about an author and their beliefs through the roles they make their characters portray. The 1847 Victorian novel, Wuthering Heights, by Emily Brontë, is no exception, especially when analyzing how Brontë uses societal norms to represent her main character Heathcliff as the hardened “criminal.” However, film adaptations have misconstrued her intentions and have portrayed him as the softened character whose unlawful actions are driven by his passion rather than his need for vengeance. This post argues that Heathcliff’s physiognomy and actions are related to Brontë’s decision to represent him as the “criminal,” while demonstrating how film adaptions have defied her intentions by decriminalizing Heathcliff to appeal to the emotional side of their audience.

Summary

Wuthering Heights takes place from 1801-1802 in Yorkshire, located in northern England, amongst the moors. The plot revolves around the lives of two fictional families: the Earnshaws who live in a farmhouse called Wuthering Heights, and their wealthy neighbors the Lintons who live at Thrushcross Grange. The story begins with a boy named Heathcliff who is adopted into the Earnshaw family as a child but faces much physical and mental abuse. When he grows older, the novel recounts his desire to get revenge on those he feels have wronged him. He does so by breaking the law where he kidnaps, abuses, and manipulates his enemies and their kin to bring them to financial and societal ruin (for more information about the plot and other characters, click here.)

Attribution-NonCommercial-Noderivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) A view of the English moors. Image by Ffion Atkinson.

Physiognomy and Personality

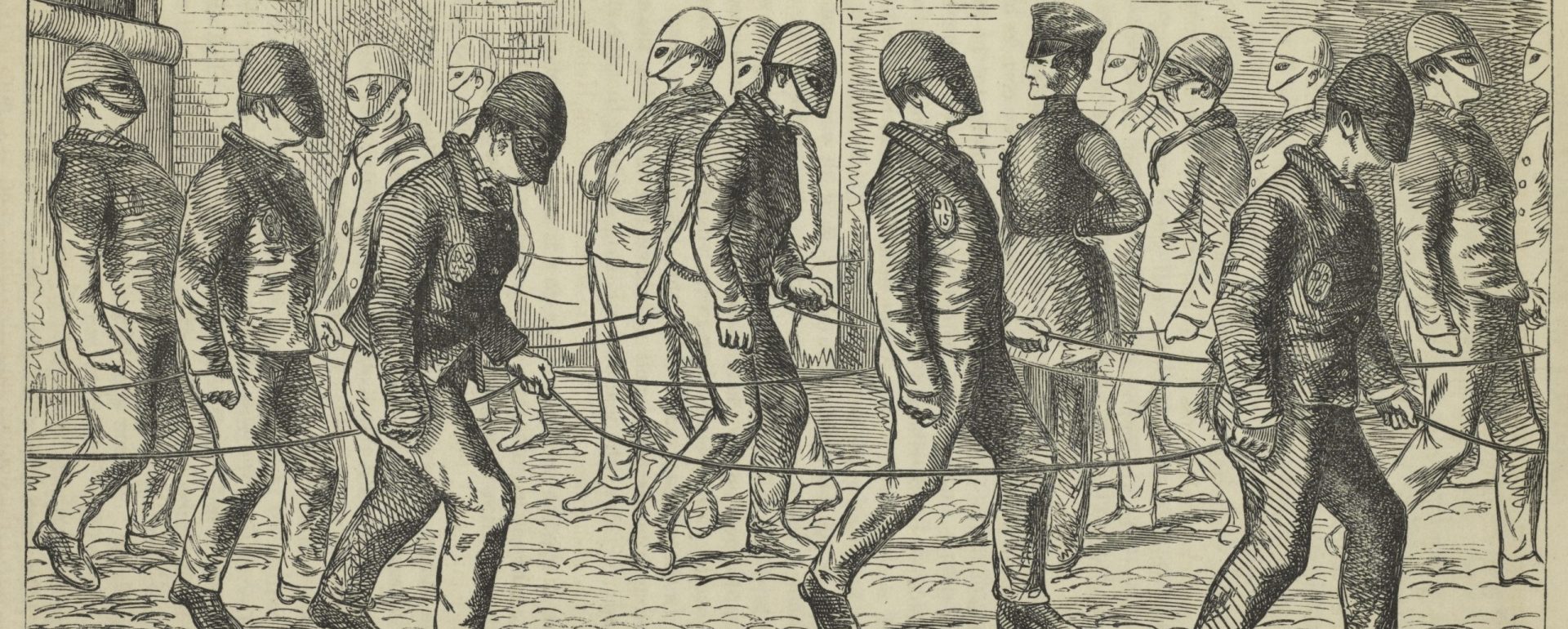

Brontë uses physiognomy to represent Heathcliff as the criminalized character in the novel. Physiognomy, though highly discredited as a study of science today, is the pseudoscience of deciphering personality from a person’s physical features, especially from the face (Campbell 1). It was a respected method during the 18thand 19th centuries to characterize personality. Brontë adds descriptions of Heathcliff’s physiognomy through his interactions with his childhood caretaker, Nelly. When Heathcliff notices that his childhood sweetheart, Catherine, is infatuated with his neighbor Edgar Linton instead of himself, he asks Nelly to help make himself more presentable. Nelly offers him advice, explaining that to alter his outward appearance, he needs to alter his personality:

Do you mark those two lines between your eyes, and those thick brows, that instead of rising arched, sink in the middle, and that couple of black fiends, so deeply buried, who never open their windows boldly, but lurk glinting beneath them, like devil’s spies? Wish and learn to smooth away the surly wrinkles, to raise your lids frankly, and change the fiends to confident, innocent angels…A good heart will help you to a bonny face, my lad… if you were a regular black; and a bad one will turn the bonniest into something worse than ugly.

Brontë 57-58

Nelly believes that the face, especially Heathcliff’s eyes, are traits that show his character, alluding to the clichéd phrase that the eyes are the windows to the soul (Fegan 5). Through his lurking eyes that act as spies for the devil, Brontë suggests that even as a child, Heathcliff has a dark soul with bad intentions. His devilish association is meant to foreshadow his representation as the “criminal” when he commits crimes of revenge as an adult. Likewise, the description of Heathcliff’s eyebrows foreshadows his role as the “criminal” because the physiognomy of “criminals” during the 19th century was characterized by the lowered and thick eyebrows (Little). Although Heathcliff’s physiognomy was described when he was a child, Brontë uses his physical features to establish his “criminality” early on, which is meant to follow him as he grows into an adult and gets his revenge.

Physiognomy and Race

Nelly’s comment regarding if Heathcliff were to be a “regular black” is an example of Brontë using physiognomy to justify racial discrimination towards Heathcliff. Since white supremacy was a large social construct during the Victorian era, this description characterizes Heathcliff as untrustworthy and a threat because he is not the “perfect” race with the facial features that are seen as preferred during this time. The uneasiness Victorian readers are intended to feel assists Brontë in criminalizing Heathcliff because it is easier to view him as evil during his revenge. For example, when Heathcliff kidnaps and abuses his enemy’s sixteen-year-old daughter, the Victorian reader is not only compelled to view him as the “criminal” because of his violation of the law, but also because of the prejudice that was established early on with Heathcliff’s description as black. This allows Brontë to make her story more compelling for her Victorian audience by giving them someone (Heathcliff) to despise because of his crimes and the race he represents, which in turn generates more profit.

Representation in Film

Although Brontë makes it clear that Heathcliff is the “criminal” in the novel, many adaptations of the book have done the opposite. Filmmakers have disregarded her intentions by making Heathcliff a softened character, who acts out of heartbreak rather than revenge, to better appeal to their audience and make more profit. While the 1939 film adaptation, directed by William Wyler and produced by Samuel Goldwyn, is viewed as the best adaptation of the novel, its portrayal of the plot and characterization of Heathcliff are far from accurate. The film completely leaves out Heathcliff’s revenge and resembles a love story between Heathcliff and Catherine, rather than focusing on the factors that lead up to Heathcliff’s criminalization.

The film shows Heathcliff’s vulnerable emotions to make him more relatable in the novel. In the film, prior to their marriage, Heathcliff sympathizes with Isabella Linton, his enemy’s sister, when she confides in him that she feels lonely living with her brother. He tells her:

You’re lonely… It’s lonely sitting like an outsider in so happy a household as your brother’s…You won’t be lonely anymore.

(Wuthering Heights 01:08:29 – 01:08:56)

Scene from Wuthering Heights (1939). All Rights Reserved by the Studio.

This sympathy from Heathcliff was never expressed in the novel and it is in stark contrast with when Brontë writes of the abuse that Heathcliff would impose upon Isabella should they be married. Heathcliff explains that:

You’d hear of odd things, if I lived alone with that mawkish, waxen face; the most ordinary would be painting on its white the colours of the rainbow, and turning the blue eyes black, every day or two; they detestably resemble Linton’s.

Brontë 159

By portraying Heathcliff to be empathetic in the film, rather than vile and abusive as described in the novel, Wyler is steering away from representing Heathcliff as a heartless “criminal” that is meant to be despised by the audience. Wyler is instead persuading the audience to build a connection with Heathcliff based on the human emotions he expresses. Rather than having the audience view Heathcliff as hardened, Wyler wants viewers to see Heathcliff’s vulnerable side because it is more marketable for audiences and can reign in more profits.

Scene from Wuthering Heights (1939). All Rights Reserved by the Studio.

Conclusion

Since the release of Wuthering Heights, many different interpretations of the plot and its characters have surfaced in the literary and film communities. Although Brontë represented Heathcliff in the novel as the “criminal” whose race and revenge are meant to be despised by readers, film adaptations have instead chosen to represent him as the heartbroken romantic. Despite their differences, both representations demonstrate how the idea of criminality can be interpreted in various ways, emphasizing the fact that no form of representation can clearly define what it means to be labeled a “criminal.”

Discussion Questions

- It is implied in the novel that Heathcliff’s evil nature is what compelled him to get revenge. However, from the abuse he suffered as a child, it can also be argued that his childhood experience was a large factor that led him towards that path. Do you think a person is born with the characteristics that make them prone to “criminal” behavior, or do you think the choice to engage in such activity may be motivated by their environment? (think about nurture vs nature)

- How do you think race affects the preconceived notions that people have towards those who are labeled “criminals”?

- When it comes to “criminal” representation, do filmmakers who make adaptations of novels, real life events, etc. have an ethical obligation to remain faithful to the original text or source, even if it may hurt their profits or restrict their creativity?

References

- Brinton, Ian. Brontë’s Wuthering Heights. Continuum, 2010. EBSCOhost, discovery.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=a98fa75c-f4f7-3ef6-898c-9764f82e020f.

- Brontë, Emily. Wuthering Heights. Penguin Books, 2003.

- Campbell, Josephine. “Physiognomy.” Salem Press Encyclopedia, Sept. 2022. EBSCOhost, discovery.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=202e098a-cf0e-312b-98d2-00d3712e7a5a.

- Fegan, Melissa. Wuthering Heights: Character Studies. Continuum, 2008. EBSCOhost, discovery.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=d840141b-309a-3966-9eb9-c29578ec1ef1.

- Little, Becky. “What Type of Criminal Are You? 19th-Century Doctors Claimed to Know by Your Face.” HISTORY, 8 Aug. 2019, https://www.history.com/news/born-criminal-theory-criminology. Accessed 26 Feb. 2023.

- von Sneidern, Maja-Lisa. “Wuthering Heights and the Liverpool Slave Trade.” ELH, vol. 62, no. 1, 1995, pp. 171–96. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/30030265. Accessed 28 Feb. 2023.

- Wuthering Heights. Directed by William Wyler, performances by Merle Oberon, Laurence Oliver, and David Niven, Samuel Goldwyn Productions, 1939.