I will be working with each of you to recommend literature that features strategies used in works you already know and enjoy. As we’re exploring in this way, I also want to give us some topics to discuss together as a class. As you read this post, I want you to be thinking about how these techniques of narrating minds that I describe impact the things you’ve read and loved (or hated!). Select at least one of the links in the Works Cited list at the end of the post to read before class on Monday (and come to class prepared with a specific passage to bring into discussion). If you select one of the literary works, I’m not expecting you to read the whole thing. If you can think of other examples of these narrative techniques, please plan to share those as well.

We observed on Wednesday that literature allows us to experience the lives of others, and this is true of all stories. We enter an alternate world with each new author we encounter, and this exposes us to circumstances and experiences we might never encounter in our own lives. The very best literature uses narrative techniques to give us these experiences in nuanced ways. As you all described the works of literature you love in our last class, my first instinct was to encourage you to think about how those stories are narrated. When you remember a story that made an impression on you, you might remember what happened in the plot or how the character felt, but it’s often hard to remember how the literary work shaped your experience. I’ve always remembered loving Beverly Cleary’s Ramona books, but I never thought much about why I did. Only when I read one recently with my son did I realize that it was because of the way Ramona’s thoughts were conveyed by the narrator. I think Cleary was using free indirect discourse (as I’ll discuss below).

First-Person Narration

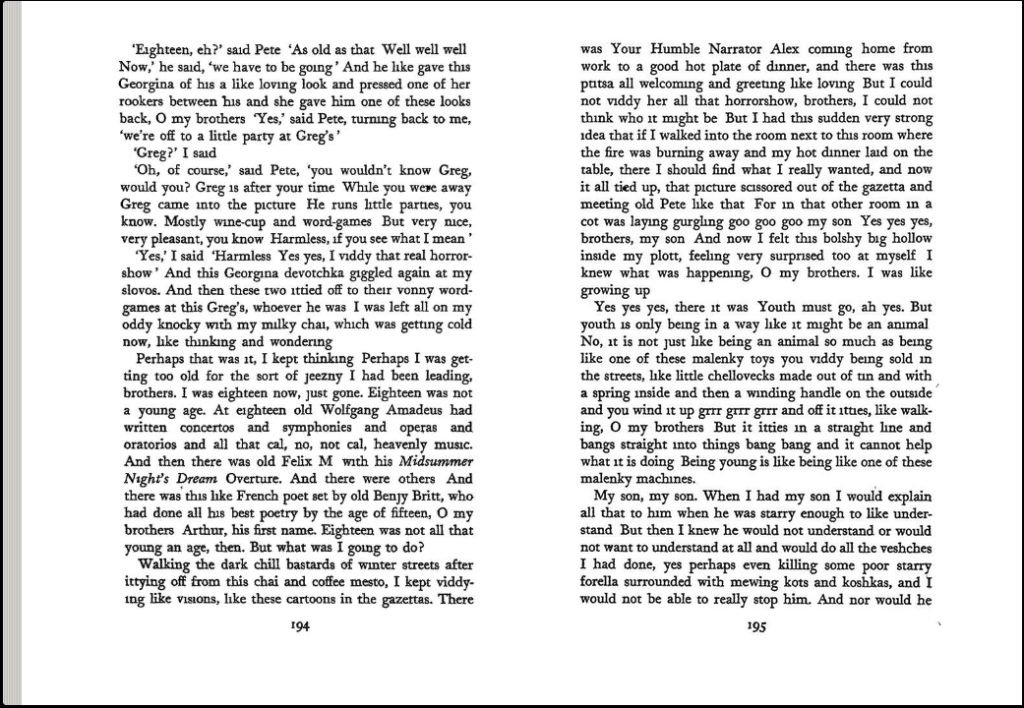

We talked in our last class about A Clockwork Orange (1962), a novel Liz selected as a favorite. After class, I looked at the example Liz brought up, the final chapter of the novel (which, interestingly, was not included in the American edition of the novel and not used in Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation). The main character narrates the novel and in that final chapter, the character describes his confusing desire for home and even a child in his own words (passage begins with “Perhaps that was it, I kept thinking…”).

This was a struggling narrator, whose own account of his feelings and actions conveys the story we receive. In this situation, the reader often becomes the wise observer of the character’s experiences–making realizations that the character might not be making. This is something called dramatic irony, a technique you might have learned about in school. When stories are narrated in this way, the reader (or viewer, if it’s a play or film) does the work of critiquing the character’s actions. We might even find in these situations that we have an unreliable first-person narrator, or, a narrator who is not telling us the full story.

Omniscient Narration

First-person narration is quite different than situations in which narrators know more than their characters and share that knowledge with readers. When I think of an omniscient or all-knowing narrator, I think of the fact that the values of that narrator shape the way they tell the story. One of the most common things I critique about literature narrated in this way is the fact that the narrator shapes the values of the world they describe. A narrator with values very different from our own can tell a story about a character or event we might celebrate, but frame a story that condemns that character or event. It can be very helpful to focus on the values of the narrator a writer has constructed (sometimes, the values are deliberately different than the writer’s actual values).

I remember being drawn into George Eliot’s Middlemarch (1872) because the narrator seemed to me wise, but not pompous. Part of this could have been that I’d already learned about George Eliot’s life and I was excited to see how she would tell a story about a young woman navigating the world. I gathered early on that the narrator had affection for the main character, Dorothea Brooke, but also was aware of her eccentricities. The narrator explains, for example, that Dorothea was “enamoured of intensity and greatness, and rash in embracing whatever seemed to her to have those aspects; likely to seek martyrdom, to make retractions, and then to incur martyrdom after all in a quarter where she had not sought it” (Eliot 2).

Angus Fletcher has a theory about why Eliot’s narrator impacted me this way. He argues that Eliot was actively working to create in fiction a method of communicating the ethic of humanism, which he describes as a new faith “that acknowledged that God was a literary myth, but denied that the sacred virtues of God–vast love, vast kindness, vast creativity–were also myths” (Fletcher “Chapter 15” n.p.). He points to a particular moment in the novel, after major discoveries in the plot and disappointment for Dorothea, when the narrator says:

Pity the laden one; this wandering woe

May visit you and me

Fletcher explains that never before in known literature had an omniscient narrator used the words “you and me” to speak to the reader. But here the narrator says, essentially: “this experience the character is having–it is something I could face or you could face.” It makes this style of narrator seem less like a divine being, separated from earthly experiences. It also makes the narrator slightly less judgmental of the failures and mistakes made by characters in the novel. If you’d like to learn more about Fletcher’s account of Eliot’s humanism and its impact on the novel, check out his full chapter linked in the list of works cited.

Free Indirect Discourse

Narration gets even more interesting, I think, when the narrator starts to sound a little bit like the character they are describing, without quoting the character directly. This free indirect narration is a technique Jane Austen uses in her novels, and many consider her the creator of the technique. Analysis abounds on the Internet about how free indirect narration works in Austen’s novels. I want to focus here on a very different kind of novel, Beverly Cleary’s Ramona the Pest. I loved all of the Ramona books growing up, and I realized while putting this post together that it might be because of how her story was narrated. I remembered Ramona as a character who always gets into scrapes, but I realize now that the narrator is often giving insight into her thoughts with what I think is free indirect narration.

It would be one thing if the narrator of the story thought that Ramona was a very silly little girl who was impulsive and made all sorts of mistakes that got her into trouble. It would also be amusing, I’m sure, to read a story narrated by Ramona. But this isn’t that either. We have a narrator who loves Ramona and wants us to understand her thinking. And so we get explanations about the world that are written as though Ramona said them (spoiler: there is no present and Ramona is very sad at the very end of her first day of Kindergarten).

Fletcher argues that free indirect discourse has a tremendous psychological impact on the reader, explaining that instead of motivating us to “embrace other people as versions of ourselves,” it encourages our brain to recognize that characters “love different things, in different ways, than we do” (Fletcher “Chapter 11” n.p.). I encourage you to read his entire chapter introducing Miguel de Cervantes, Henry Fielding, and Jane Austen to get a sense of his full argument linked in the list of works cited below.

Stream of Consciousness

And then we have the technique of sharing the flow of thoughts that run through a character’s mind, perhaps with very little explanation from a narrator. This technique emerged as William James was developing the ideas that formed the field of modern psychology. Stream of consciousness narration is done in a variety of ways, beautifully described by Fletcher in his chapter introducing William James, Marcel Proust, James Joyce, and Virginia Woolf, where he explains that the effect on the reader is “to encourage us to feel a slight separation from our consciousness, as if we’re observing our own ideas from without” (Fletcher “Chapter 17” n.p.). I encourage you to read the chapter if you’d like to learn more about stream of consciousness.

If you want to just experience an example of stream of consciousness with zero introduction and then tell us what you think of it, jump directly to the wonderfully irreverent final section of James Joyce’s Ulysses, which features the stream of a consciousness of Molly Bloom with almost no punctuation. An interesting context for this famous narration of a woman’s perspective (written by a man) is Brenda Maddox’s biography of Joyce’s wife, Nora, who was a major source for his creation of Molly (if you create an Internet Archive account, you can check Maddox’s book out online).

Works Cited

Anthony Burgess. A Clockwork Orange. 1962. Internet Archive, http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.182027.

Cleary, Beverly. Ramona the Pest. William Morrow & Company, 1968.

Eliot, George. Middlemarch. 1891. Internet Archive, http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.42254.

Fletcher, Angus. “(11) Ward off Heartbreak: Jane Austen, Henry Fielding, and the Invention of the Valentine Armor.” Wonderworks: The 25 Most Powerful Inventions in the History of Literature, First Edition, Simon & Schuster, 2021.

—. “(15) Bounce Back from Failure: George Eliot’s Middlemarch and the Invention of the Gratitude Multiplier.” Wonderworks: The 25 Most Powerful Inventions in the History of Literature, First Edition, Simon & Schuster, 2021.

—. “(17) Find Peace of Mind: Virginia Woolf, Marcel Proust, James Joyce, and the Invention of the Riverbank of Consciousness.” Wonderworks: The 25 Most Powerful Inventions in the History of Literature, First Edition, Simon & Schuster, 2021.

James Joyce. Ulysses. 1922. Internet Archive, http://archive.org/details/ulysses2018.

Maddox, Brenda. Nora : A Biography of Nora Joyce. London : Hamish Hamilton, 1988. Internet Archive, http://archive.org/details/norabiographyofn0000madd.