Transforming Humanities Texts: Open Editions Built For and With Students is an open pedagogy project supporting this revitalization of the core curriculum. The public page for the project is on on the Rebus website, but this page includes new ideas as they emerge.

To support our “core within the core” initiative, a team of faculty (and eventually students) are building a set of documentary editions for use in core courses. While the connected core is unique to our institution, most of the texts we will include are taught around the world. We invite faculty to make use of these open editions, and we provide the assignments and technical guidance to get started. This project brings scholarly editing into conversation with open pedagogy.

NOTE: this page is one huge messy draft of thoughts that I’m sharing in case they spark ideas for others–the posts in the drop-down menu offer slightly more refined thoughts.

Thoughts Toward An Introduction

(to be made available under CC BY to be included at the start of each edition and potentially expanded to include particular editorial choices made by faculty and students)

The texts in this anthology were not produced for you. Well, that’s not exactly accurate. The editions you see here were produced very specifically for you. In fact, they’re still being revised for you and we actually hope that you’ll contribute work so that your name will someday become a part of it. I say that the texts weren’t produced for you because the text you’re about to read was published in a different time and place. It’s been edited to be read in a new context. You are the new context, but we also want you to dig into the earlier contexts of these stories, plays, essays, and. We want you to think about who produced them and how they were received. [more questions]. This is the work of humanistic inquiry and we believe it emerges from genuine questions that you formulate when encountering things that are perhaps a little confusing. And so we don’t give you answers with our introduction and notes. Because, it’s almost a cliche to say this at this point, but there are no wrong or right answers to the kinds of questions we want you pursuing.

[a section in the works–this will lay the groundwork for two distinct but related activities. One will be on students’ web presence (and an environmental scan of their current digital footprint). The other will be on copyright and open licenses as it relates to choices students get to make about their work being incorporated] Think about how student content will be licensed and work this into the assignment. Talk about what copyright means and what licenses enable. Think about how the materials students find to incorporate into their annotations need to follow these same principles. This text is/isn’t in the public domain, meaning it is free to [draw on language from Duke’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain] it. The work you will produce in this course could be incorporated into a future edition, and so you will get to make decisions on how you license your contribution [expand].

Key Features

This project is intentionally open-ended/never complete.

Faculty produce editions for use in courses and, through a series of assignments, faculty and students increase and improve the editions by producing new introductory materials, suggesting better structure, and crafting more helpful notes. One might peruse the collection as it grows through multiple interfaces: one organizes texts according to where they are in their editorial process, another organizes texts chronologically, still another situates texts on a map according to place of publication.

Documentary Editions

We’re producing documentary editions, which means that the person initiating an edition selects a specific (in most cases) physical copy of their chosen text to represent digitally. This is done to remind students that the texts they are reading have existed in many different editions since the date of first publication. By setting aside the emphasis on an authoritative critical edition (usually complete with annotations representing the pinnacle of scholarly thinking at the moment it was published), these editions put students in a position to explore these texts alongside their instructors to ask questions and decide afresh how they might be relevant to their lives.

Additional Features

- This open educational resource is designed to be usable off-line (you can download a pdf of any text in the anthology at any time, and an entire print copy can be assembled at the start of the semester based on the course schedule

- It’s build on WordPress, making it easy to join and contribute to this project using a platform you can use in the real world.

- These editions are designed to be deployed in many platforms or on your own personal website. If you’re at the University of New Haven, though, the simplest way to use it is by cloning it for your own course at the University of New Haven.

- This project is executed through assignments. The best way to get started is to adopt or adapt one of the assignments included here. The work you get from your students will be ready for inclusion in future editions.

- The project is also supported through open educational resources related to scholarly editing and open pedagogy: we will encourage editions to be built with Oxygen (or FairCopy) and TAPAS, though the final XML files will be transformed into HTML for publication in WordPress. Or perhaps there’s some other way to do this. I’m still thinking about it.

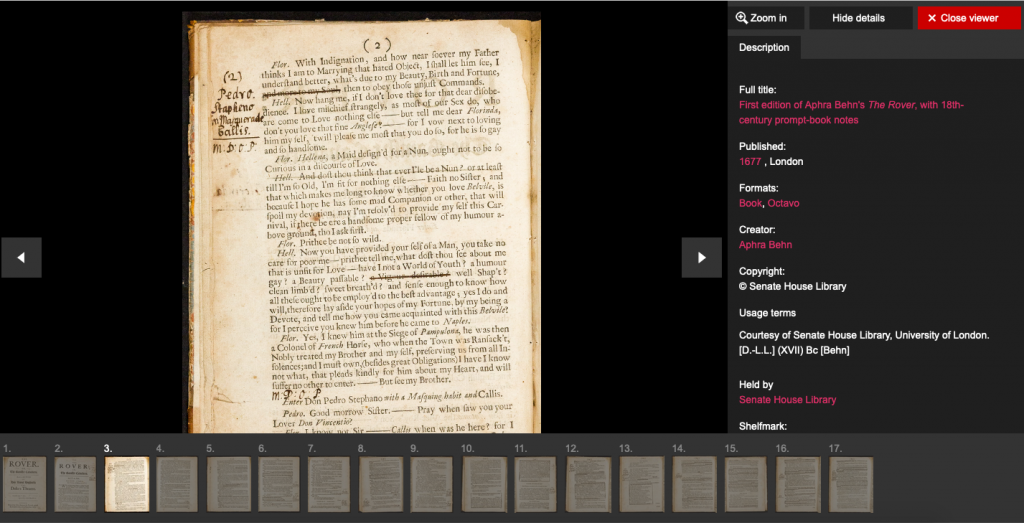

For as long as technology has facilitated the inexpensive reproduction of text, teachers have been making copies of things to assign to their students. This is a good thing; it usually indicates that teachers are doing whatever they can to bring the best materials together for students (at the lowest cost). What winds up happening, however, is that students are not able to get a full grasp on the contexts in which the things that they are reading were originally produced (and revised and adapted in interesting ways over time). As an undergraduate, I read 18th-century plays from photocopied packets, and never thought about the fact that actors would have used the physical playtext as a prompt-book during rehearsals. The British Library’s publication of a selection of digitized images invites one to consider this use. It’s not just The Rover, it’s a first edition of the play, published in 1677, with prompt-book notes.

I read photocopies of scholarly articles, and never thought much about the issue of the particular journal in which that article appeared. How was that issue produced? Who edited it and what was that editorial process like? These are questions I never thought to ask because I didn’t encounter it as a physical object…an artifact. The documentary editions we are producing preserve those features in a digital format, inviting students to ask questions about them.

For my first-year writing course, I assign a webpage produced by D.L. Ashliman to present 7 versions of Little Red Riding Hood. It’s part of a much larger open educational resource that is truly impressive in scope and attention to detail.

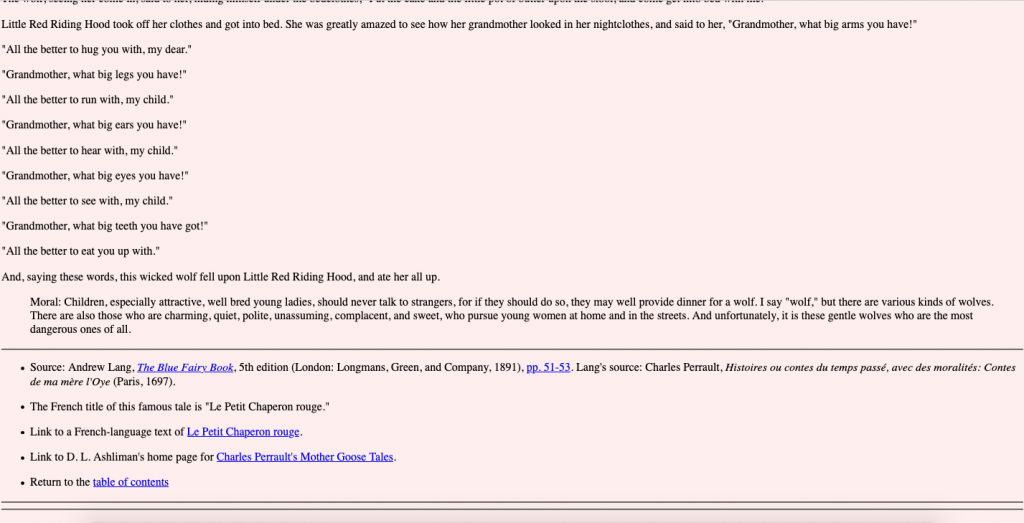

I was creating a page in Pressbooks called “Versions of Little Red Riding Hood,” pasting in full-text versions I could find online, but I switched to Ashliman’s website because of the detail he includes about his sources. This is what appears at the end of Perrault’s “Little Red Riding Hood.”

This project builds on what Ashliman has done to create a set of standards faculty can use when producing their own copies of by using the principles of scholarly documentary editing to make it very clear what we are doing when we reproduce texts for our students. We are creating new editions, and if we do so deliberately, we’ll open up a new layer of understanding for our students.

I want to try this out. How should I chose the edition of the text I’m teaching?

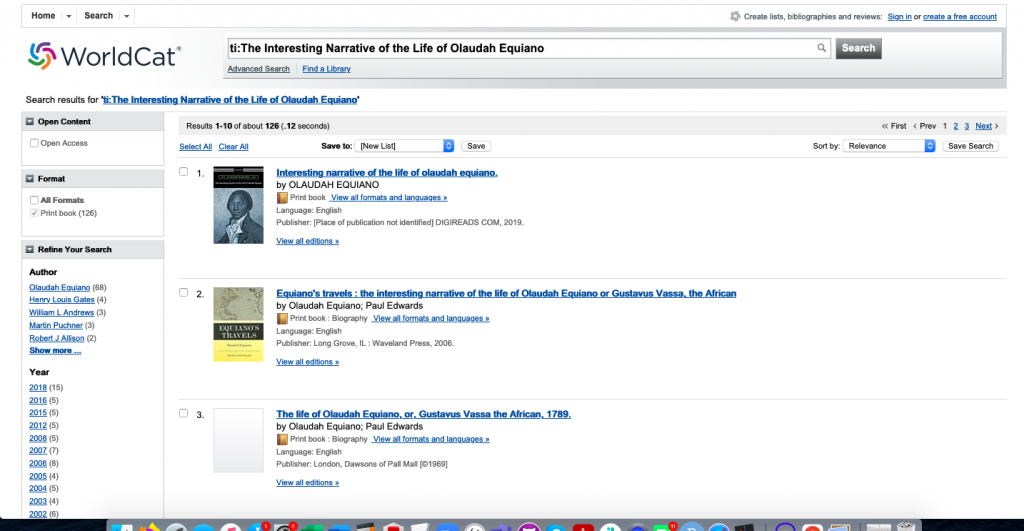

You could approach this in many ways. You might begin with the edition you own and work from that, complete with your marginal notes and other unique features (my own Wal-Mart copy of Jane Eyre makes a regular appearance in the classroom when I teach that text). It might be that the Internet Archive (Project Gutenberg is a part of this initiative) or Google Books already has scanned an edition and made a (potentially rough) transcription available. There are often many editions of texts already scanned, so it could be useful to browse there. You might also see if there are physical copies of the edition you want to work with held at a library with whom we could partner. A good way to search for this is to go into WorldCat. As you can see below, you can refine your search by date.

Looking at this list of editions, we might ask a few questions: would it be more fruitful for students to read the very first edition of The Interesting Narrative of the life of Olaudah Equiano or would it be better to look at an edition from 1967, when WorldCat records 15 different editions being available, or 1969, when there were 10?

The important thing to keep in mind is that you will want students to think about the particular edition you’ve selected as a physical object–a thing that was produced at a particular time with a particular purpose. You might plan on introducing other editions into class discussion to help them think more about how the story has already been transformed over time. Indeed, this is an interesting way to bring in fair use excerpts from copyrighted translations or contemporary adaptations.

What if I want to assign copyrighted material?

This project is going to take full advantage of fair use to make copyrighted materials available for learning. One way of doing this will be for the editor of a copyrighted text to produce a documentary edition of the text that includes only a percentage of the full text (and the students would buy the entire text if it were going to be assigned in full). With each new use of the text, additional sections can be made available in the anthology. We will need guidance on this, but we don’t want to assume we have to exclude copyrighted texts from this anthology. I’m also hoping to reach out to Open Editions to learn how they are handling permissions for their work with James Joyce (actually, they just started working with Joyce as his texts moved into the public domain, most likely).

I also think we might develop a strategy for reaching out to authors of copyrighted work (well, more like their publishers) to see if they will agree for texts to be included–an excerpt if not the entire thing. What would that hashtag look like on Twitter? We might also say that the cost of trade novels and comics and films are not in the same category as “textbooks,” produced specifically for students and rapidly increasing in price (let’s not forget, of course, about what I call the “common read industrial complex”–trade publishers eager to get a little slice of the higher ed, required reading pie). We’ll especially want to think about things that are born digital and already fully accessible online, though perhaps not reproducible. Artists who are selling NFTs…how could that be relevant?

Another thought about copyright–what if the assignments are adapted for copyrighted material to just have students collaborate to create viewing guides (for films) or introductory materials for particular editions (complete with references to page numbers)…things that don’t actually have to be attached to a digital facsimile or transcription of the thing itself? It’s a way to proceed with the “students decide how things are relevant” even if digital editions of the copyrighted material is not available.

What do I do when the annotations start to get too cluttered? For how many iterations do I assign this to students as a project they contribute to?

Great question. It’s up to you, and we likely won’t know what will be best until we start to do it and use these editions in teh classroom. It could become like a Nicholson Baker novel (see below) or you might reign it in after a certain amount of time.

Related Projects

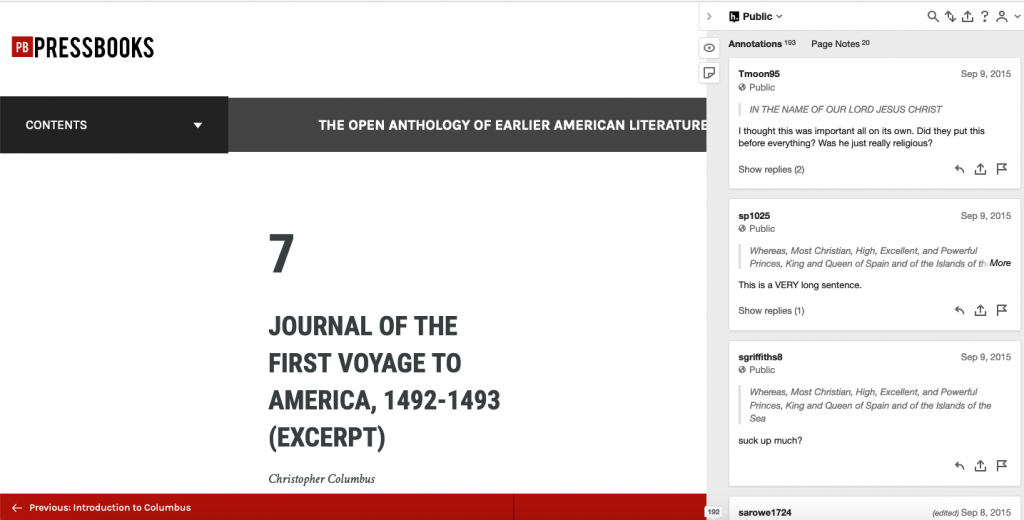

The Open Anthology of Earlier American Literature

My early experiments with engaging students as editors of course materials were inspired by Robin DeRosa’s Open Anthology of Earlier American Literature, which later became a REBUS project. You can see below how the early editions are delightfully filled with irreverent student annotations.

The goal with this project is that student annotations become a part of a new edition (this will actually be our measure of success…how many instructors and students work on transforming an early edition to incorporate contributions and suggestions from students). These annotations will become part of the edition, and the student and faculty contributors who created them will be credited. This will make it possible for annotations to speak across editions. Think the footnotes in Nicholson Baker’s novel Mezzanine, but including multiple voices.

The Book Traces project

I’ve also been inspired by the Book Traces project, which began at the University of Virginia in response to the same digitization of texts that is facilitating this project. I think it provides a useful way to think about the traces on physical books in relation to the annotations we’ll be creating for digital editions of a physical book. If you were going to check a book out of the library to read it for a course, you might find evidence of former students’ reading. That might be amusing or it might be irritating. In most cases, the former readers of that text didn’t have you in mind when they were marking up the text. This markup’s for you. And you’ll be invited to add to it. We want to make sure to retain the power of personal annotations, however. Students will be encouraged to annotate for themselves and to decide whether they want to share those early responses publicly, with a private course group, or keep them completely private.

Hypothesis

The very first Hypothesis education webinar, hosted by Jeremy Dean, brought Robin DeRosa, Elisa Beshar-Bondo, and Larry Hanley together for a conversation that I joined as a respondent. There was a really interesting debate that emerged during that conversation that I think usefully illustrates the relationship between open pedagogy and scholarly editing–a conversation I would like to enter with this project.

Stretching Existing Technology

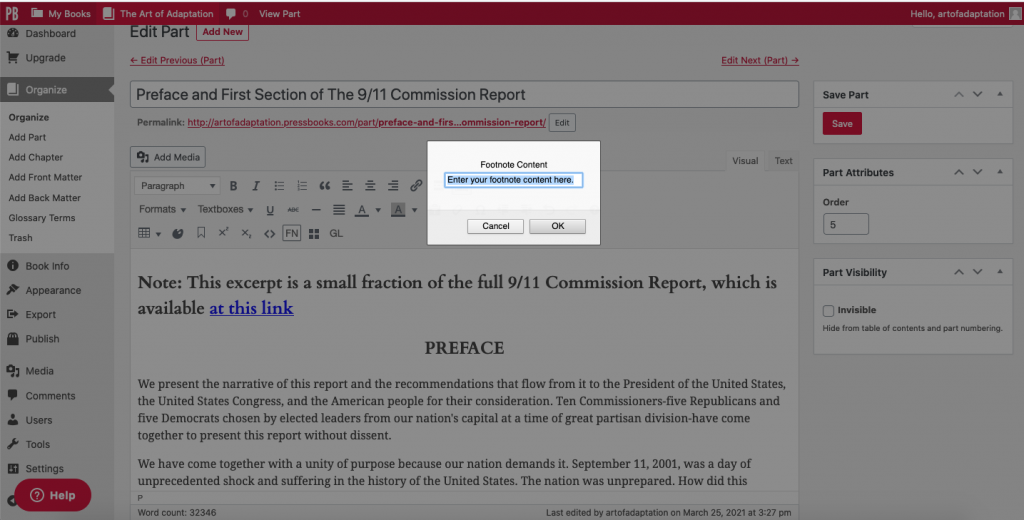

Pressbooks (for HTML markup)

Pressbooks enables the addition of a footnote, with a small area to add the footnote. This could also be done with HTML as part of the learning process for participants, and the footnote could be styled in a particular way according to standards in the project, using HTML markup.

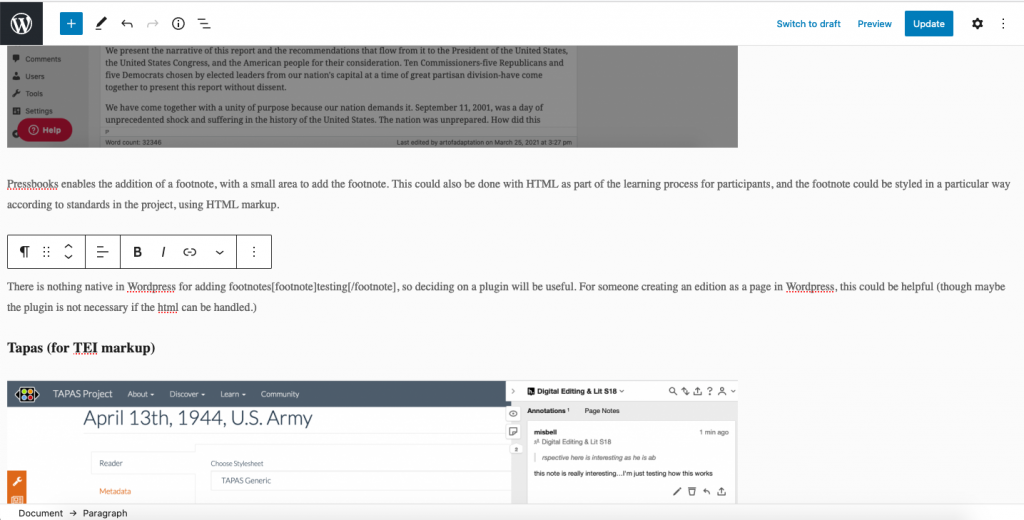

WordPress (for HTML markup)

There is nothing native in WordPress for adding footnotes[footnote]testing[/footnote], so deciding on a plugin will be useful. For someone creating an edition as a page in WordPress, this could be helpful (though maybe the plugin is not necessary if the html can be handled. Just tested this and that’s not the case. The CSS for the theme won’t recognize and transform the footnote tag, so that’s why a plugin is necessary…I think).

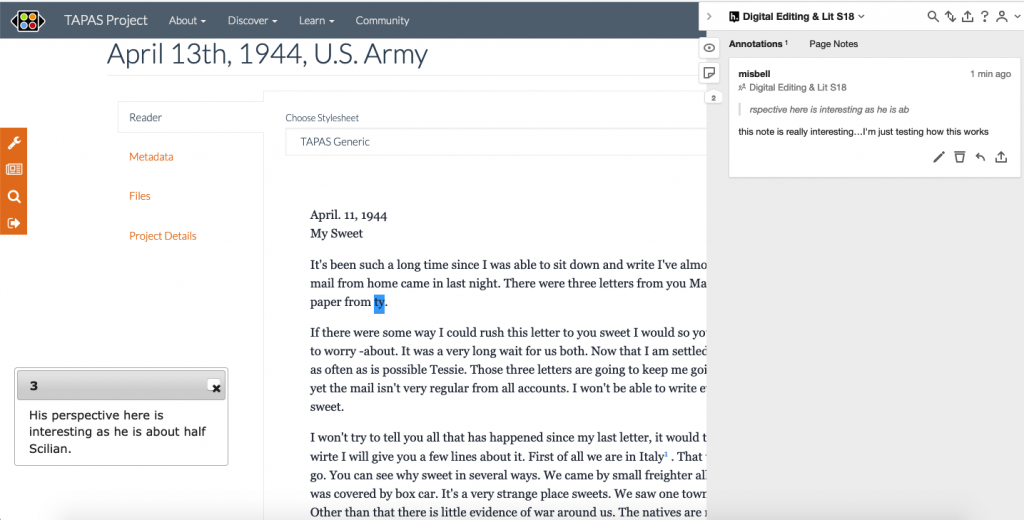

Tapas (for TEI markup)

Tapas uses Java to display notes as in a pop-up window. This doesn’t interact well with Hypothesis. If a student were to annotate a note, the annotation would remain, but accessing it later would not prompt the pop-up to reveal itself. This (and other things) suggest that collecting notes on the page with the complete text (perhaps in a new way…perhaps at the bottom of each physical page) will be preferable for this style of reading. Would it be interesting for students to be able to see published footnotes as they read? Or does gathering them at the bottom make more sense? Could they toggle between two options?

When thinking about the annotations, I’m thinking more and more that students might be able to choose to read the text without any notes OR the text with notes (at least my use of it might be that) and they could annotate either version because we’d be using hypothesis in the wild so I wouldn’t need to only load one version for them into Canvas. It really will be best to have the TAPAS toggle available for students to see what’s going on. The TAPAS toggle. I want to harness the power of the TAPAS toggle.