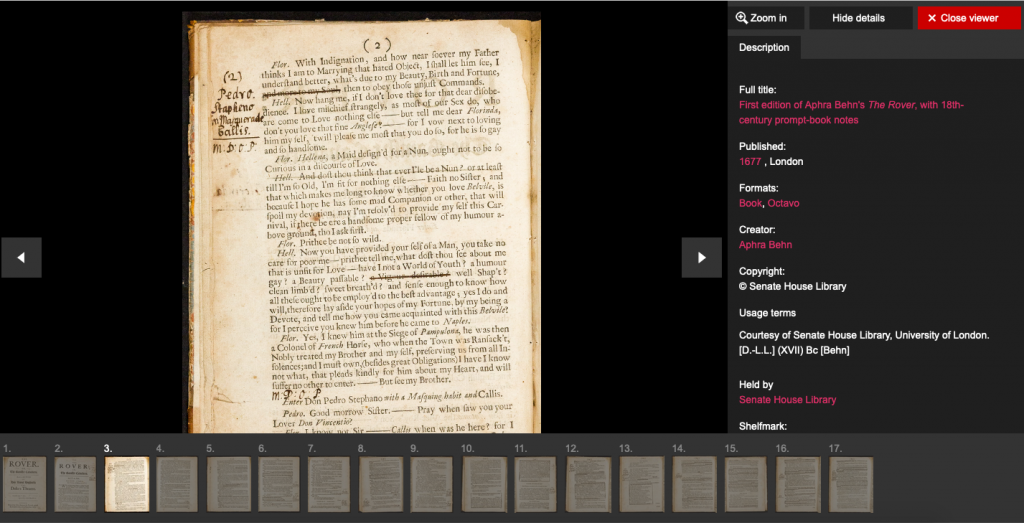

For as long as technology has facilitated the inexpensive reproduction of text, teachers have been making copies of things to assign to their students. This is a good thing; it usually indicates that teachers are doing whatever they can to bring the best materials together for students (at the lowest cost). What winds up happening, however, is that students are not able to get a full grasp on the contexts in which the things that they are reading were originally produced (and revised and adapted in interesting ways over time). As an undergraduate, I read 18th-century plays from photocopied packets, and never thought about the fact that actors would have used the physical playtext as a prompt-book during rehearsals. The British Library’s publication of a selection of digitized images invites one to consider this use. It’s not just The Rover, it’s a first edition of the play, published in 1677, with prompt-book notes.

I read photocopies of scholarly articles, and never thought much about the issue of the particular journal in which that article appeared. How was that issue produced? Who edited it and what was that editorial process like? These are questions I never thought to ask because I didn’t encounter it as a physical object…an artifact. The documentary editions we are producing preserve those features in a digital format, inviting students to ask questions about them.

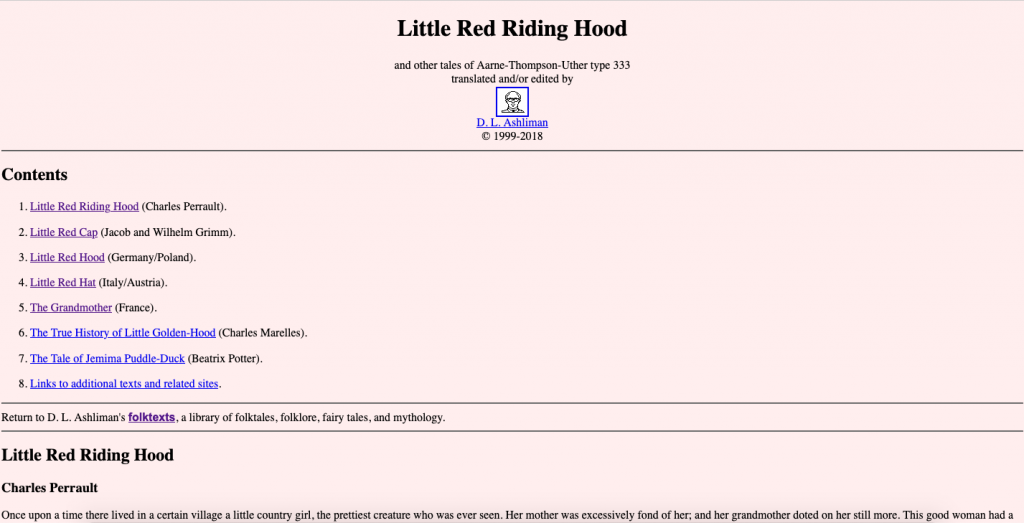

For my first-year writing course, I assign a webpage produced by D.L. Ashliman to present 7 versions of Little Red Riding Hood. It’s part of a much larger open educational resource that is truly impressive in scope and attention to detail.

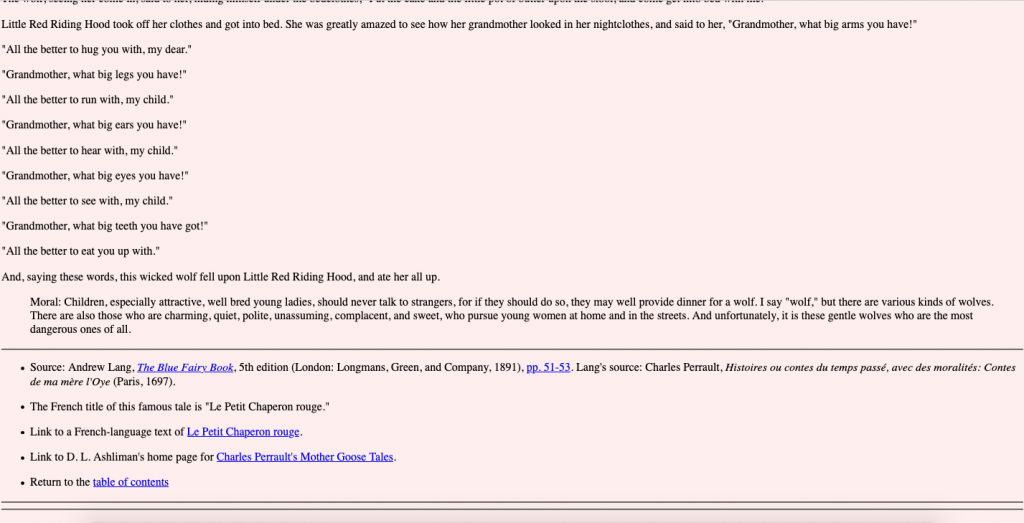

I was creating a page in Pressbooks called “Versions of Little Red Riding Hood,” pasting in full-text versions I could find online, but I switched to Ashliman’s website because of the detail he includes about his sources. This is what appears at the end of Perrault’s “Little Red Riding Hood.”

This project builds on what Ashliman has done to create a set of standards faculty can use when producing their own copies of by using the principles of scholarly documentary editing to make it very clear what we are doing when we reproduce texts for our students. We are creating new editions, and if we do so deliberately, we’ll open up a new layer of understanding for our students.

I want to try this out. How should I chose the edition of the text I’m teaching?

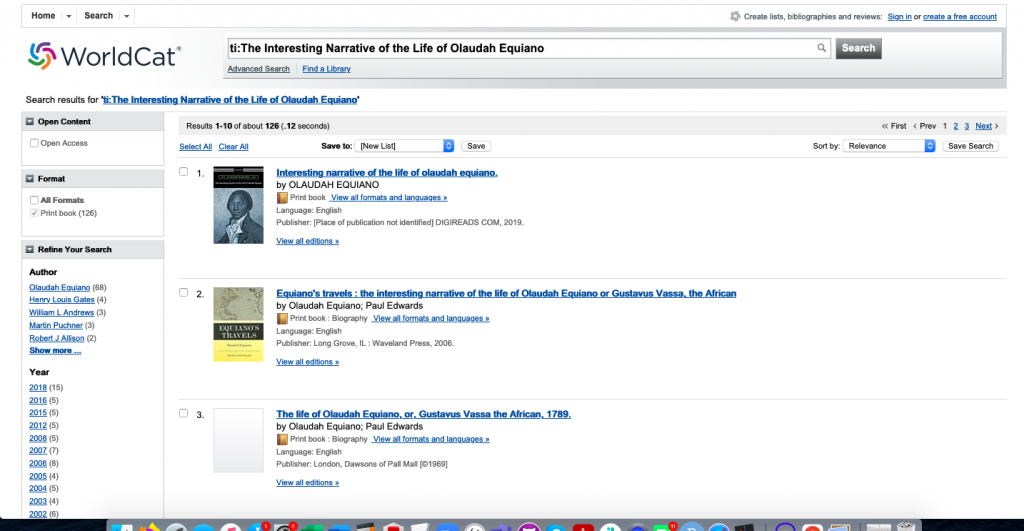

You could approach this in many ways. You might begin with the edition you own and work from that, complete with your marginal notes and other unique features (my own Wal-Mart copy of Jane Eyre makes a regular appearance in the classroom when I teach that text). It might be that the Internet Archive (Project Gutenberg is a part of this initiative) or Google Books already has scanned an edition and made a (potentially rough) transcription available. There are often many editions of texts already scanned, so it could be useful to browse there. You might also see if there are physical copies of the edition you want to work with held at a library with whom we could partner. A good way to search for this is to go into WorldCat. As you can see below, you can refine your search by date.

Looking at this list of editions, we might ask a few questions: would it be more fruitful for students to read the very first edition of The Interesting Narrative of the life of Olaudah Equiano or would it be better to look at an edition from 1967, when WorldCat records 15 different editions being available, or 1969, when there were 10?

The important thing to keep in mind is that you will want students to think about the particular edition you’ve selected as a physical object–a thing that was produced at a particular time with a particular purpose. You might plan on introducing other editions into class discussion to help them think more about how the story has already been transformed over time. Indeed, this is an interesting way to bring in fair use excerpts from copyrighted translations or contemporary adaptations.

What if I want to assign copyrighted material?

This project is going to take full advantage of fair use to make copyrighted materials available for learning. One way of doing this will be for the editor of a copyrighted text to produce a documentary edition of the text that includes only a percentage of the full text (and the students would buy the entire text if it were going to be assigned in full). With each new use of the text, additional sections can be made available in the anthology. We will need guidance on this, but we don’t want to assume we have to exclude copyrighted texts from this anthology. I’m also hoping to reach out to Open Editions to learn how they are handling permissions for their work with James Joyce (actually, they just started working with Joyce as his texts moved into the public domain, most likely).

I also think we might develop a strategy for reaching out to authors of copyrighted work (well, more like their publishers) to see if they will agree for texts to be included–an excerpt if not the entire thing. What would that hashtag look like on Twitter? We might also say that the cost of trade novels and comics and films are not in the same category as “textbooks,” produced specifically for students and rapidly increasing in price (let’s not forget, of course, about what I call the “common read industrial complex”–trade publishers eager to get a little slice of the higher ed, required reading pie). We’ll especially want to think about things that are born digital and already fully accessible online, though perhaps not reproducible. Artists who are selling NFTs…how could that be relevant?

Another thought about copyright–what if the assignments are adapted for copyrighted material to just have students collaborate to create viewing guides (for films) or introductory materials for particular editions (complete with references to page numbers)…things that don’t actually have to be attached to a digital facsimile or transcription of the thing itself? It’s a way to proceed with the “students decide how things are relevant” even if digital editions of the copyrighted material is not available.

What do I do when the annotations start to get too cluttered? For how many iterations do I assign this to students as a project they contribute to?

Great question. It’s up to you, and we likely won’t know what will be best until we start to do it and use these editions in teh classroom. It could become like a Nicholson Baker novel (see below) or you might reign it in after a certain amount of time.