| Creator | J.A. Simpson and E.S.C. Weiner |

| Media Form | Text |

| Genre | Dictionary Definition |

| Technique | Etymology |

| Date and Location of Creation | 1989 in Oxford, England |

| “Predator” Represented | multiple |

I’ve been asking a lot of questions lately about how animals come to be understood as predators. I’ve learned that predation (and even diet, as in “carnivore,” or “herbivore”) are not factored into how animals are classified scientifically. Instead, they are classified according to their morphology (how their bodies are structured) and, more recently, according to their DNA. As Carissa Shipman explains, “Prior to being able to sequence DNA, organisms were described and categorized solely by their distinct morphologies (physical characteristics) and ecological roles.” I thought that maybe carnivorous animals would share certain features (powerful teeth and sharp claws, for example) and herbivorous animals would share certain features (multiple stomachs for digesting plant matter) so that animals classified together could automatically be thought of as “predator” or “not-predator.” But even that isn’t really the case. All therapods (the famous T-Rex is a therapod) were initially thought to be carnivorous, but this is being challenged by modern paleontology. The typical diet of a species and its instinct to hunt, in other words, are not part of their scientific classification.

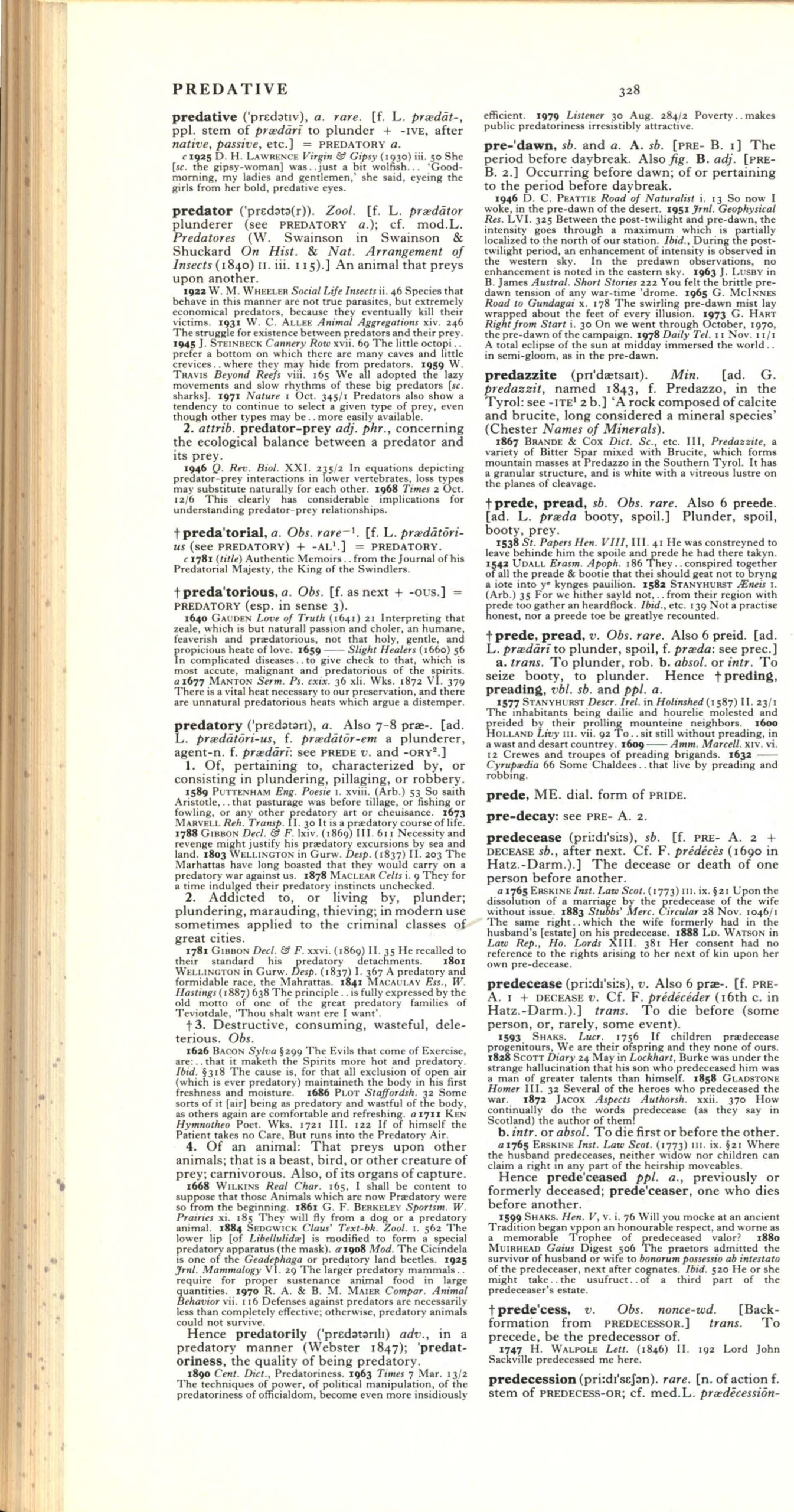

So, what is a predator and where did the word come from? The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) offers our best insight into this question because it captures the earliest known usage of words in the English language. The image at the top of this post is taken from the 1989 edition of the OED, which suggests that the word “predator” was used as a noun in the nineteenth century to mean “an animal that preys upon another.” The Online Etymology Dictionary explains that the root is the Latin word praedari “to rob, to plunder.” In the OED, the adjective “predatory” was used to describe human behavior earlier than the nineteenth century: “Of, pertaining to, characterized by, or consisting in plundering, pillaging, or robbery.” I was surprised to find this out and I think it has some pretty big implications for my thinking about why humans create representations of meat-eating animals that glorify their predatory behaviors. I’m still sorting out my thoughts on this, and I’m eager to hear what you think when we discuss in class. The rest of this post introduces many representations of predators that I hope will inspire a direction for your blog post. Please read this full post and then select at least one of the items in the works cited list to read in greater depth before class on Monday.

Wolves

| Creator | Mojang Studios |

| Media Form | AI-Driven Entity |

| Genre | World-Building Video Games |

| Technique | Programming in Java and C++ |

| Date and Location of Creation | 2011 in Stockholm, Sweden |

| “Predator” Represented | Wolf |

My son has started playing Minecraft. He’s about two months into this adventure, and a few weeks ago, while I was making dinner, I heard him cry out in agony from the living room and then start sobbing. “I was trying to tame the wolf,” he said, “but I killed it.” I think the sound he heard was the “wolf death” sound in the video to the right.

Devastating. As we talked more about what happened, I realized that he was less upset about accidentally killing the wolf than he was afraid that he might not come across another wolf. I thought he felt guilty for killing an innocent creature; he just really wanted an opportunity to tame a wolf.

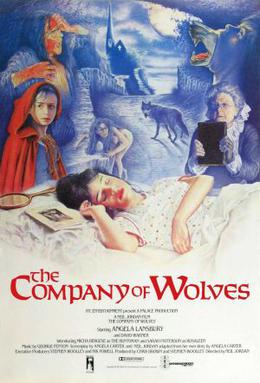

I thought I’d write this post about representations of dinosaurs and sharks, the two animals that immediately come to my mind when I think about representations of predators. But this experience with a Minecraft wolf reminded me of other depictions of wolves as predators. When I teach first-year writing, I often have students look at versions of little red riding hood (many versions are gathered at this fantastic site by Professor D.L. Ashliman). My students have heard the story as children, but few realize that it has been adapted countless times across media in the hundreds of years it has been circulating through human communities. There are two modern retellings that usually attract the most attention, A 1997 film by David Kaplan called “Little Red Riding Hood” and Angela Carter’s short story “The Company of Wolves” (1979), which was made into a delightfully disturbing horror film in 1984. Both offer fascinating representations of predation that could inspire a project for this unit (find them all at the bottom of this post!). Anyone digging into a version of little red riding hood would also do well to also explore Jack Zipes’ introduction to The Trials and Tribulations of Little Red Riding Hood (also linked from the bottom of this post).

Minecraft wolves also made me think of Jack London’s famous novel White Fang. This summer, I re-read White Fang by listening to a Librivox recording of it. I was struck by the early chapters, when three men and a team of sled dogs are making their way through the Yukon are hunted by a pack of wild wolves. Though I was listening to an audio recording of the novel, I was left with a strong image of the climactic moment in chapter three, “The Hunger Cry,” when only one man, Henry, remains (the rest of the men and dogs have fled and, we imagine, have been eaten by wolves). The man is exhausted and his only defense is the fire that will go out if he falls asleep. The wolves are surrounding him and waiting for him to collapse and the narrator lingers on Henry’s realization that he is meat. He is many things, and he is also meat:

As he piled wood on the fire he discovered an appreciation of his own body which he had never felt before. He watched his moving muscles and was interested in the cunning mechanism of his fingers. By the light of the fire he crooked his fingers slowly and repeatedly, now one at a time, now all together, spreading them wide or making quick, gripping movements. He studied the nail-formation, and prodded the fingertips, now sharply, and again softly, gauging the while the nerve-sensations produced. It fascinated him, and he grew suddenly fond of this subtle flesh of his that worked so beautifully and smoothly and delicately. Then he would cast a glance of fear at the wolf-circle drawn expectantly around him, and like a blow the realization would strike him that this wonderful body of his, this living flesh, was no more than so much meat, a quest of ravenous animals, to be torn and slashed by their hungry fangs, to be sustenance to them as the moose and the rabbit had often been sustenance to him

White Fang as serialized in The Outing Magazine (1906), Volume 48 p. 139

I encourage you to listen to the novel yourself on Librivox, or, if you’re curious to imagine how the first people who read the novel would have experienced it, check out the entire issue of The Outing Magazine that the first section of the novel appeared in.

Dinosaurs

John Green’s podcast, The Anthropocene Reviewed, contains a marvelous episode on velociraptors. Why? Because his seven-year old son recommended the topic. Green does a brilliant job summarizing what most dinosaur-obsessed kids and adults already know: the fictional depiction of velociraptors in Jurassic Park does not match what paleontologists knew at the time the book was written. What John Green doesn’t do in his episode is think about why Michael Chrichton and the team adapting the novel into the 1993 film created this representation of predators.

I encourage you to listen to the first half of the episode devoted to velociraptors, but I have to pull a quote for emphasis:

Crichton based his velociraptors on a different dinosaur, the Deinonychus, which did live in present-day Montana and was the approximate size and shape of Jurassic Park’s velociraptors, although Deinonychus was also feathered, and, you know, not smart enough to open doors or whatever. Crichton took the name velociraptor because he thought it was “more dramatic,” which presumably is also why the theme park is called Jurassic Park in the book, even though most of the dinosaurs in the park did not live in the Jurassic Age, which ended 145 million years ago, but instead in the Cretaceous Age, which ended 65 million years ago with the extinction event that resulted in the disappearance of around three-quarters of all plant and animal species on Earth, including all large species of what we now consider dinosaurs.

Transcription of episode made available on John and Hank Green’s Nerdfighteria Wiki

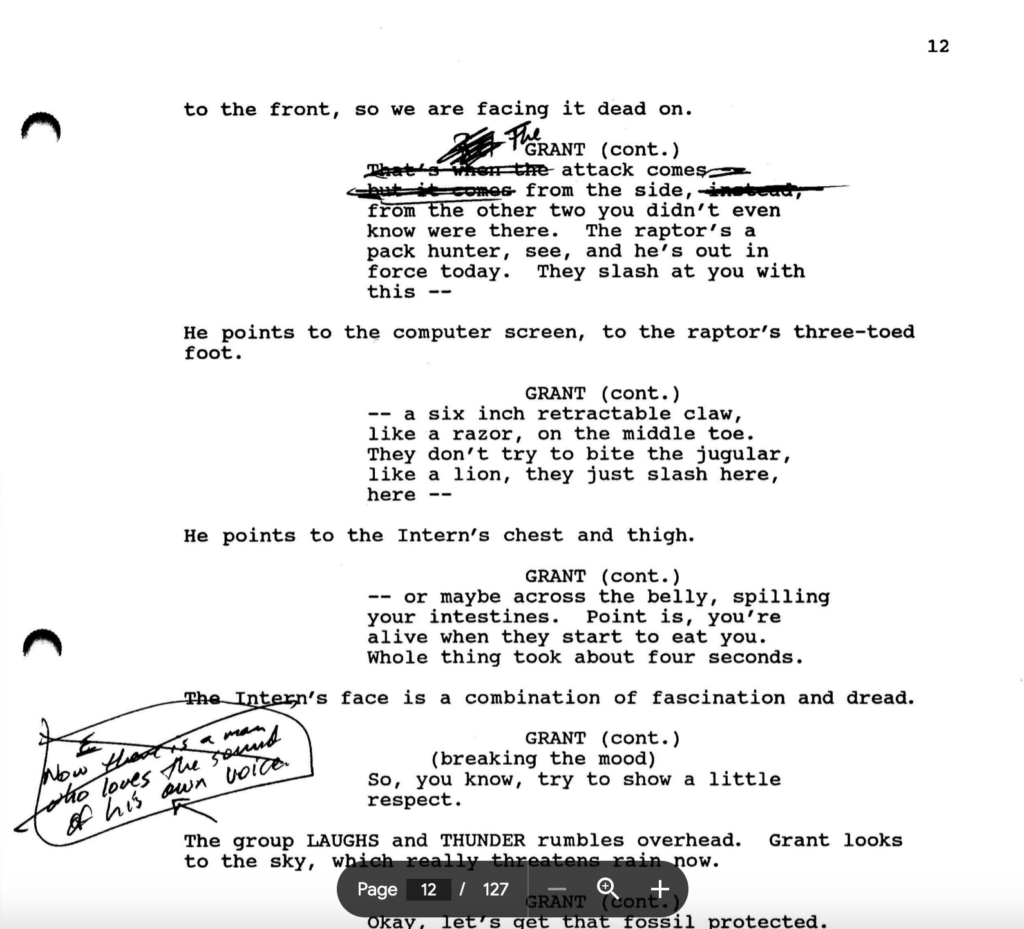

I hope this will encourage you to dig into why and how humans have decided to represent dinosaurs as predators. Perhaps a place to begin would be to look at the way Michael Crichton’s novel was adapted for the screen:

Should Humans Try to Eliminate Predation?

There are some thinkers who argue that predation is something we as humans should work to eliminate, even for “wild” animals. In her recent book Justice for Animals: Our Collective Responsibility, the philosopher Martha Nussbaum argues that humans need to admit that we (humans) already control the experiences of the species we share the planet with. Nussbaum published an excerpt of the book as an essay in The New York Review of Books and I encourage you to read the entire essay if you’d like to think more about humans and their role in the lives of nondomesticated animals (link to the essay in at the bottom of this post). Just to get you started, though, here is how Nussbaum introduces predation as a problem:

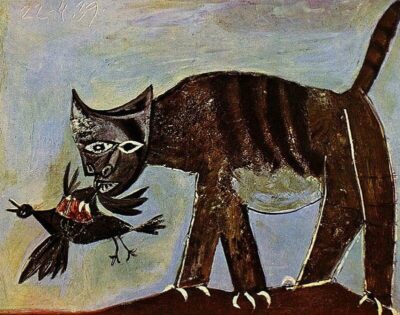

Stewards of large animal reservations not only do not inhibit predation; they often strongly encourage it. They behave, then, very differently from companions of domesticated animals, who typically discourage their companion dogs and cats from feasting on little birds or hunting foxes, even though that behavior is part of the typical repertory for some breeds. That is, they typically treat their companion animals rather like children: they channel natural aggression in the direction of some form of substitute activity, preventing frustration of instincts, but also preventing harm to others. Just as a child is steered in the direction of competitive sports rather than human carnage, so a cat is steered to a toy or a scratching post rather than to a bird.

Martha Nussbaum, “A Peopled Wilderness” The New York Review of Books

She goes on to imagine what it might be like if humans could engineer predation out of existence—helping wild animals with an instinct for predation find other outlets for their deadly inclinations (as we do with our domesticated companion animals). She does not have a perfect solution, but discusses ideas that have been circulated. She concludes her essay by emphasizing that predation is a problem:

Too many people grow up excited and enthralled by predation, and this has had a bad effect on our entire culture. It’s important to keep pointing out that antelopes were not made to be food; they were made to live antelope lives. The fact that so often they do not get to live those lives is a problem, and since we are in charge everywhere we need to figure out how much we can and should do about it.

Martha Nussbaum, “A Peopled Wilderness” The New York Review of Books

What is our role in the lives of nondomesticated animals? Does our sense of this role change if we acknowledge that we are impacting their lives whether we are hunting them or not? Is there a reality of predation that exists outside of human language (a question we also asked about species)? These are a few of my questions. I’m eager to hear yours. To prepare for class on Monday, please select at least one of the sources cited below to explore in greater depth. Take notes on what you read, watch, or listen to (including page numbers and timestamps!) so you can share your thoughts and direct us to the spot as we discuss in class.

Works Cited

Carter, Angela. “The Company of Wolves.” The Trials and Tribulations of Little Red Riding Hood, Ed. Jack Zipes. New York: Routeledge, 1993

Jurassic Park (1993) |Dr Grant Explains Kid about Raptors |1080p HD. Directed by NERDX CULTURE, 2019. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WgQe68kF_8M.

Koepp, David. Jurassic Park. https://davidkoepp.com/script-archive/jurassic-park/. Accessed 13 Oct. 2023.

London, Jack. White Fang (Version 2). Read by Mark F. Smith. https://librivox.org/white-fang-by-jack-london-librivox-version-2/. Accessed 14 Oct. 2023.

Nussbaum, Martha C. “A Peopled Wilderness.” The New York Review of Books. 8 December 2022.

“Predator | Etymology, Origin and Meaning of Predator by Etymonline.” Onlne Etymology Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/word/predator. Accessed 13 Oct. 2023.

The Outing Magazine. Vol. 48, Open Court Publishing Co, 1906. Internet Archive, http://archive.org/details/sim_outing-sport-adventure-travel-fiction_1906-05_48.

Zanno, Lindsay E., et al. “A New North American Therizinosaurid and the Role of Herbivory in ‘Predatory’ Dinosaur Evolution.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 276, no. 1672, Oct. 2009, pp. 3505–11. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.1029.

Zipes, Jack. “The Trials and Tribulations of Little Red Riding Hood (Introduction).” The Trials and Tribulations of Little Red Riding Hood. New York: Routeledge, 1993.