Smallpox has been around a long time. We have records of it from the 4th century CE, and much more in-depth records in more recent times thanks to in-depth Chinese medical texts. According to the CDC, mummies found in Egypt suggest that smallpox may be at least 3,000 years old. While this leaves a bit of a gap in its history (between mummified remains and the next record being a much more recent Chinese text), the CDC also has quite a comprehensive record showing how smallpox spread following trade routes.

This story sounds familiar. Growing up I heard plenty of stories of how plagues were carried on trade ships by rats, fleas, or people, but it didn’t end with plagues. When my parents planted a scraggly Japanese maple tree in our front yard (affectionately named Susan), my mother worried constantly about Japanese beetles eating away at the other trees in the area. While I don’t remember if there was ever an issue with the beetles for our tree, I do remember wondering why people would bring in plants from other areas if they knew it could cause problems. My parents told me that sometimes these things happen because people are selfish, but sometimes they can’t be helped. As we began our conversation about invasive species, I began to turn that concept around in my head. Could smallpox outbreaks have been helped? Could it have been contained to certain parts of the world, and is that a fair thing to ask? But more importantly, why was it that when we discussed invasive species I kept thinking of how we talk about infectious diseases?

The featured image, which can be found on the CDC’s “about” page, is a clean and sleek look at a CDC building. The colors are bright, the saturation turned up, but the color palette is still cool. I would not be inclined to suggest that the building was inviting, but the image does its best to make it seem that way. Perhaps the effort to make it more welcoming comes from a place of wanting to counter the language often associated with the CDC. “Control efforts”. “Prevention”. “Eradication”. “Harm to human health“. As we began our discussion on invasives, I started to wonder: are these phrases about diseases, or are they about invasive species? As it turns out, each one of those words or phrases exists regularly in both contexts. There is significant overlap in how we think about them, and I was curious about whether or not that matters.

Control

On the USDA’s web page on Federal Government’s Response for Invasive Species there is a selection of links to various task forces specializing in invasive species along with brief descriptions for each. Within the six task forces and their descriptions, the word “management” is used 6 times and the word “control” is used 3 times, somewhat interchangeably. When I noticed the repetition of the terms, I could not help but think about Nussbaum’s “A People’d Wilderness”. The claim that “since we are in charge everywhere we need to figure out how much we can and should do about it” seems to reverberate throughout the endless pages on invasive species. But why do we want so desperately to have control over these species? Most of this seems to come from a fear of the potential harm inflicted by invasives, but how do we measure harm, and is our desire for control linked more closely to our desire to limit impact on the environment or impact on ourselves? Well, to answer these questions, I decided to look at how we try to exert control, and how these efforts parallel those of disease control. This journey first took me to itap.gov, The Federal Interagency Committee on Invasive Terrestrial Animals and Pathogens, simply because the committee’s title included pathogens. The committee mostly seems to focus on gathering information that might be of value to other groups which more directly deal with the consequences of invasive species and pathogens. While it is an important service that cannot be downplayed, it did not fit quite what I was looking for, so I kept digging.

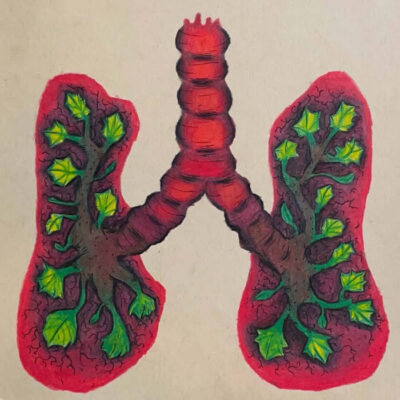

The Department of Energy & Environment (DOEE) in Washington, DC provides a simple, easy-to-read list of methods for controlling invasive plants. This list opens with “biological control methods”, which include “plant diseases or insect predators, typically from the targeted species’ home range”. This got me thinking about two things: first, it was interesting that a solution to an invasive species involved the introduction of another species with the goal of destroying another species. That just seemed like setting yourself up for more problems, but I’m no expert and there would most likely be plans in place to limit the impact outside of the target species. Secondly, that sounds an awful lot like training the environment to defend itself against the species, almost like how vaccines train the body to be able to fight against viruses. According to the CDC’s smallpox history, early control efforts consisted of exposure to material from smallpox sores, which did result in symptoms but “fewer people died… than if they had acquired smallpox naturally”. This later became the basis of vaccine research, which started with the goal of “annihilating” smallpox. It is interesting to me that a successful method of control is to bring in other outside risks to build the ability to fight a larger threat (which is not to say that vaccines are a threat, but that early smallpox control efforts still carried significant risk). This, then, leads to more questions: how do we weigh risk, and who is doing the weighing?

Eradication

Smallpox has been eradicated. There is no doubt that should be cause for celebration; Vox even released an article titled “Why the world should celebrate Smallpox Eradication Day” which emphasizes the significance of the feat. After all, that is the end goal of vaccinations. The word “eradication” has a brutal connotation to me. The idea is total obliteration, to cease to exist, to become nothing more than the memory of a bad taste in the mouth. It seems fitting for something the CDC called “a terrible disease” and which sparked global efforts against it. But is it a fitting way to talk about cats? Or pythons kept as pets and released into the wild, no fault of their own? Well, that seems harsh. But what about those Japanese beetles threatening the trees in my yard? Or jumping worms devouring the much-needed nutrients for my garden? Or locusts? Or an introduced plant that chokes the life out of the ones already there? The more I think on this, the harder it is to find a line to draw, and the more I find myself looking for someone on which to pin the blame. But that becomes a difficult game as well. If I travel to Europe to visit my aunt and bring a head cold with me that erupts throughout countless countries, is there really fault? If some ants crawl onto my friend’s cruise ship and hop off on an island where they destroy whole ecosystems, can we really expect people to stop going on cruises? It’s easy to set limits on the exotic pet trade, but what can we really say once someone breaks the rule and suddenly there are pythons all over Florida? In the end, does blame really matter when these species make a place their home? Do these creatures (who exist and expand simply because they are where they are) deserve total eradication? Who makes those decisions, and who is drawing the lines?

Well, the ITAP committee has established themselves as a group that assesses the impact of invasive species and pathogens. But there are individual people behind the title of “committee” and those people have to wrestle with the lines they draw. It is easy to hesitate about the eradication of stray cats. We feel connected to them, responsible for them, and in many ways they remind us of ourselves. Who can blame them for wandering around to see new sights, for befriending others of their kind, and for inadvertently spreading diseases and decimating populations of other species along the way? It’s certainly a familiar story. It makes sense that it might be easier to draw those lines for plants, which might be more difficult for us to connect to as they are harder to anthropomorphize. But plants can communicate, and what is more human than that? Then, at least we can agree that viruses aren’t even living, so we can certainly eliminate those without a stain on our consciousness. Right? Well, according to an article from Scientific American by Luis P Villarreal which (like many others) calls into question the livingness of viruses, it has “defied a simple answer all these years because it raises a fundamental issue: What exactly defines ‘life?'”. While this post doesn’t necessarily have the time to address such a complicated question, I’ll leave you with another: what would it mean to our battles against disease if we were to consider that viruses were living things?

Harm

Who is being harmed by invasive species? Once again I find myself thinking of lines drawn in the sand. Who is drawing the lines, who gets hurt when the lines are crossed, and how much do we determine which lines are worth caring about? Stray dogs, for example. Growing up in New England I have seen very few stray dogs at all. I’ve known people who raised and rescued wolf-dogs, and countless families that kept dogs of all shapes and sizes, but I have seen maybe one stray dog in all my 25 years here. But when visiting family in Arizona, stray dogs were so common that many of them were known throughout the community, and rarely did they spark conversation aside from when brought up by people from out of town (me). It made me wonder about the dogs, their quality of life, but also about the other animals in their environment. What were the dogs eating? Were the plants in the area suffering? And did anyone care?

When it comes to diseases, it is an obvious answer. People care when people are harmed, and the level of care increases with the risks involved for people. Smallpox killed 3 out of every 10 people it infected. Those are devastating numbers, and those it didn’t kill were often left with severe scars and other long-term issues. But again, even my language is beginning to suggest that smallpox acted with intent, as if it was a murderer on the loose meaning to slaughter its hosts. Is it alive? Is it meaning to hurt us? It is us vs them? If it is, are we and our lives worth more than those we perceive as invaders? Now, I don’t mean to suggest that we should stop fighting diseases. I like being alive and illness-free, as I’m sure is true of most people. But our language around something we fundamentally see as harmful and scary is spilling out into other areas, our perspectives merging in sometimes unexpected ways. Acting out of self-preservation makes sense, but it is worth taking the time to understand why we are thinking about things with the language we use. After all, it might not be a virus on the other end of our thoughts.