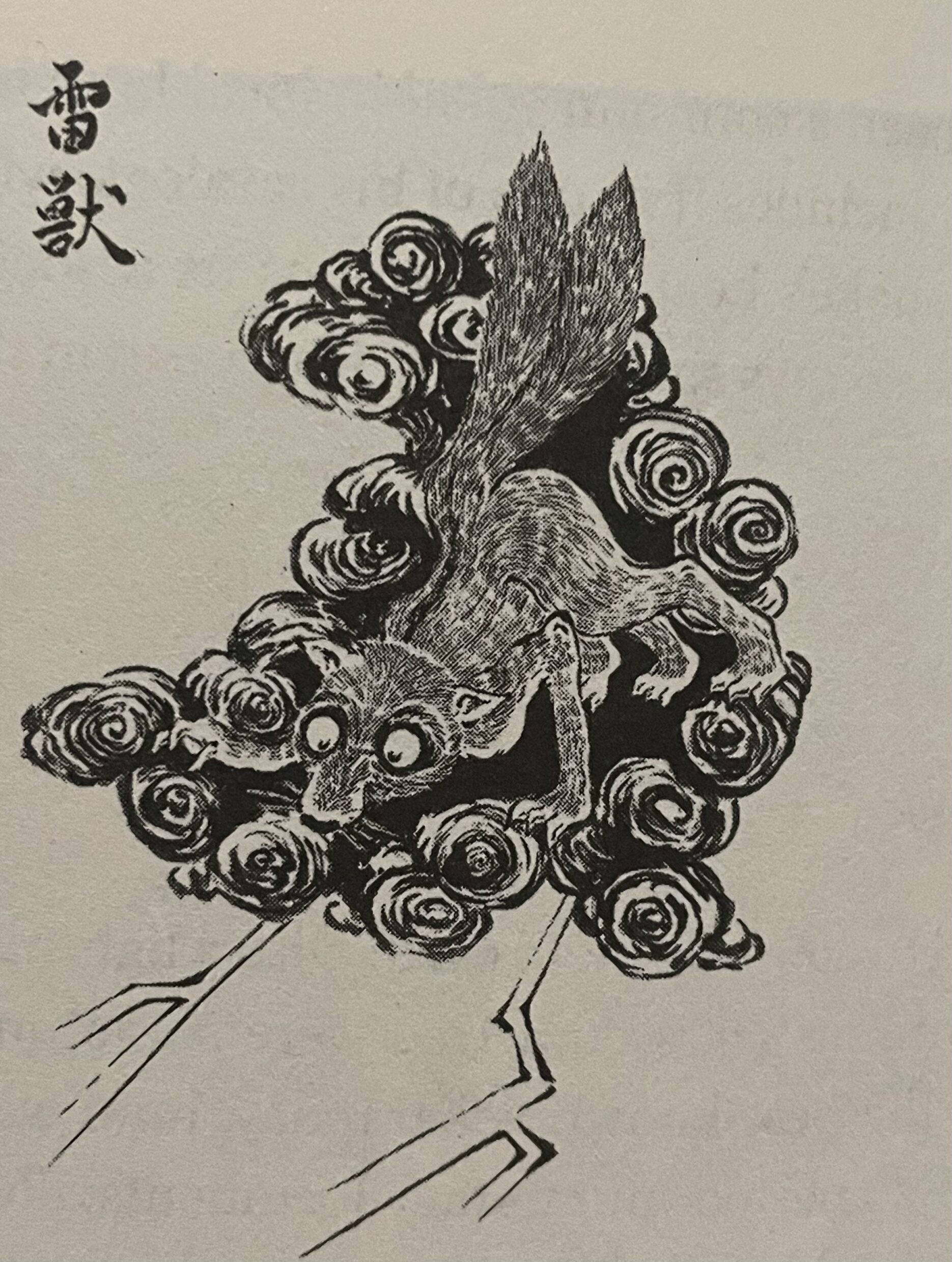

| Creator | Shinonome Kijin |

| Media Form | Illustration |

| Genre | Folklore Depiction |

| Technique | Presumably Physical Illustration that was then Digitally Scanned |

| Creation Date | Published in 2015 |

| Publication Information | Produced for and published in The Book of Yōkai |

| Invasive Species Represented | Masked Palm Civet |

As a streak of sporadic light crashes upon an unfortunate tree, bellowing its might as it reduces the great wood to scattered splinters, an onlooker views the sight with fear. After being sufficiently scared, the Japanese traveler peeks at the ruins, noticing a small figure jump out of the wreckage. This, to the Edo-period civilian, was an instance of a raijū, an electrical spirit, one of many of what’s called a Yōkai in Japan. Sightings of these supposed travelers from the sky were common during the Edo period (1603-1868), becoming a well-known, mythical explanation for lightning strikes. According to eye-witnesses and artists who would draw their interpretations of this beast, the raijū was a mammal typically around the size of a dog, frequently given shimmering fur to mimic the bolt of energy that it rode upon.

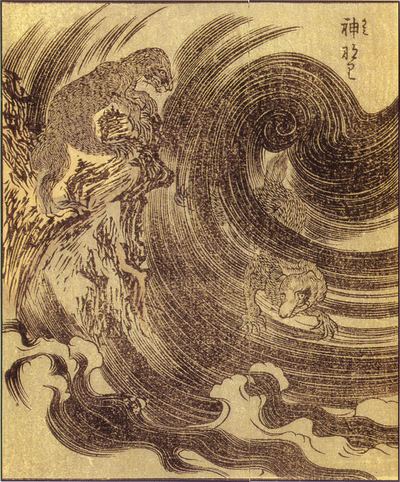

A heavenly creature who rocketed through the sky was bound to attract attention, and have stories passed around regarding what features could be made out during the lightning flash it arrived upon. Such speculation from various eye-witnesses would eventually lead the raijū to become a Yōkai with quite a bit of renown, and would thus end up finding itself interpreted and drawn into a variety of encyclopedias of the Edo period as cataloguing information grew in popularity, typically with titles involving the phrase “hyaku-monogatari” which translates to “one hundred stories” (Foster 43). The image below for example was illustrated by Takehara Shunsen for such a compendium titled Ehon Hyaku Monogatari, where a pair of raijū are depicted, one perched upon the top of a tree, another traveling through powerful gusts of wind. Compendiums, whether they be centuries old such as the Ehon Hyaku Monogatari, or recent iterations such as Michael Dylan Foster’s Book of Yōkai from 2015 demonstrate a continued fascination to capture the powerful and mysterious figures of Japanese folklore, such as the sky-walker turned invasive tree-dweller such as the raijū.

by Takehara Shunsen apart of the public domain

As the centuries progressed, folklore such as Yōkai began to be placed under scientific scrutiny, where the mystic explanations to old mysteries were given rational answers. Modern biologists and folklorists began to look towards the depictions of these invaders from the clouds, attempting to narrow down the likely suspect via analyzing what animal best matched the various drawings from ancient illustrations and bestiaries. Michael Dylan Foster, folklorist and author of The Book of Yōkai, presents a popular modern theory regarding the raijū’s true identity. Rather than an animal native to Japan, the fallen lightning embassies are in fact an alien species, Paguma larvata, the masked palm civet (198).

Masked palm civets, colloquially known as hakubishin by the Japanese, aren’t native to the isolated island country. Rather, the species evolved and thrived in various southeastern Asian countries, notably China, Borneo, and Taiwan. Many posit that civets were brought over to Japan during a post World War II craze, where the animals were popular exotic pets, before eventually escaping their owners and becoming part of Japan’s ecosystem. However, as Foster notes in The Book of Yōkai (2015), “Because Edo-period images of raijū bear a striking resemblance to these creatures…some scholars are now convinced that hakubishin have been in Japan since much earlier” (198). It leaves the civet in a perplexing situation in Japanese history and culture, as many might call this small mammal invasive, but it’s impact on the ecosystem in past centuries was so minimal yet its appearance common enough, that many didn’t know the animal’s presence on the island except through the lens of the supernatural.

The civet’s placement in Japanese ecology opens up various points of discussion regarding the very concept of invasive species, including how dominant an animal must be to be deemed this hostile, destructive word rather than just be called an nonnative species. The association with raijū, a literal other-worldly spirit, would also imply that the civet was acknowledged as a strange subject that still managed to blend into both Japan’s culture and ecosystem. Throughout The Book of Yōkai, Foster poses this idea that Yōkai as a whole are meant to represent transitions between conflicting sides, of reality and fiction, of nature and society, of right and wrong. It’s rich then that the raijū’s real identity is also an example of the border between native and alien, a hermit and a chameleon of Japanese ecology. It’s a species that represents the inherent struggle in determining what we as humans, as observers, can deem invasive.

The National Institute for Environmental Science (NIES), a Japanese organization, notes on their page about masked palm civets that these intruders are indeed an invasive species, having a range close to encapsulating all of Japan. Yet the only parameters for this qualification, according to the NIES’ page describing their qualifications for invasives, is simply “organisms that have been moved by humans to areas outside of their natural distribution range.” Such a definition feels like it lacks nuance, especially given the connotation and assumed reaction it gives someone when hearing how a creature is invasive. Seen with campaigns against animals such as spotted lanternflies or cane toads, invasives are typically viewed as ecological threats that should be stomped out whenever seen. Such a strong implication means it’s important to carefully place the label upon a species, especially one that’s been a part of the ecosystem for centuries, as is the case with the civet if the “raijū” drawing are accurate. Frankly, the NIES’ classification of the civet as an invasive species seems dubious at best, but to fully explain why, it’s necessary to explore the very definition of the term.

The United States Department of Agriculture provides a definition for invasiveness that’s in the right direction, having more depth than the NIES’ proposal, describing invasive species on their information center page as “non-native (or alien) to the ecosystem under consideration and whose introduction causes or is likely to cause economic or environmental harm or harm to human health.” While I personally believe the classification should center on primarily the ecological harm a species brings to an area rather than economic, it’s a much more compelling definition which would warrant the negative perception of invasive species that so many hold. Expanding on the ecological point, it’s a fair observation to note that the harm a foreign species introduces into an environment shouldn’t simply be ecological competition for a niche, but rather a crushing presence that suffocates native fauna and flora. Even this is a blurred line however, how much pressure can a new species place before being classified as invasive? How soon can we mark a species as relatively safe? These questions really take form when analyzing the masked palm civet and how it’s faring in modern Japan.

Returning to the NEIS, they note that the civet only affects two native species, the native raccoon, referred to commonly as a tanuki or raccoon dog, and the extremely vague generalization of “crops.” Ignoring the blatant oddity that is considering “crops” as an entire species with no specifications, the tanuki is a fascinating point to raise against the civet. The two mammals are both nocturnal omnivores, though the tanuki doesn’t share the civet’s arboreal lifestyle. It’s natural to assume then that the similar niche the civet and tanuki fill could cause ecological problems, reducing the population of either of these critters. However, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) instead marked both of their species which are of “Least Concern,” even noting on the paguma larvata page that, as of 2016, the civet’s population has been on a decrease. Such a situation would suggest then that the NIES’ marking of the civet’s effects are overblown, and the title of invasive is rather harsh, especially as habitat loss due to humans are the only real threats to either animal.

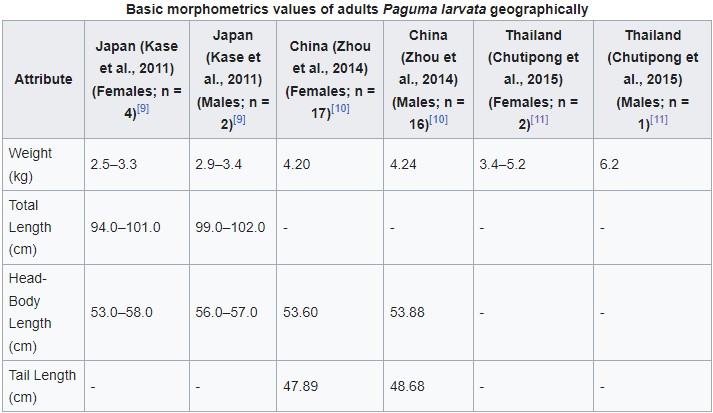

The masked palm civet’s uneventful ecological impact over centuries make it questionable if they should even be marked as an invasive species anymore. This idea can be further pushed with how civets have seemingly experienced some small level of evolution over all these years, an assertion made possible by reviewing their morphometric values. By comparing the average length and weight of different masked palm civet populations, specifically the Japanese and Chinese variants, it can be seen the island group is becoming slightly lighter on average compared to their mainland counterparts. Further studies on these values would naturally reveal this idea’s validity, but if this is a widespread change in Japan’s civet population, it would imply these former-Yōkai don’t dominate the native ecosystem, and instead had to adapt rather than showcase the supposed might they had as sky ambassadors during the Edo period.

It’s hard to believe an “invasive” species such as the masked palm civet was able to still infiltrate the rich culture of Japan that scholars from east to west dedicate years researching. Such a strange in-between of foreign and native represented by the arboreal scamp seems poetic as it once held the position as a messenger from heaven, riding on the swift and shattering power of lightning to remind humanity of what used to be unknown to us. Civets now, however, can become a messenger exemplifying the complexity of invasiveness, and how we may need to reexamine what researchers have considered known, prompting us to come up with a more fitting term for species that have slotted into their new homes without causing ecological catastrophe. As Foster accurately asserts before moving onto the next Yōkai in his compendium, “the discussion [of the relationship between raijū and civets] inspires productive interaction between folkloric knowledge and scientific inquiry” (198).

Works Cited

Foster, Michael D. The Book of Yōkai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore. U of California P, 2015, p. 197-98.

International Union for Conservation of Nature. “Masked Palm Civet.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 2015, www.iucnredlist.org/species/41692/45217601. Accessed 10 Nov. 2023.

—. “Raccoon Dog.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 2016, www.iucnredlist.org/species/41692/45217601. Accessed 10 Nov. 2023.

Kase, Chihiro, et al. “The Effect of Body Size on Shapes and Sizes of Gaps Entered by the Masked Palm Civet (Paguma Larvata).” Mammal Study, vol. 36, no. 3, 1 Sept. 2011, pp. 127-133.

National Institute for Environmental Studies. “Paguma Larvata / Invasive Species of Japan.” 国立環境研究所, www.nies.go.jp/biodiversity/invasive/DB/detail/10200e.html. Accessed 1 Nov. 2023.

United States Department of Agriculture. “What Are Invasive Species?” National Invasive Species Information Center (NISIC), www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/what-are-invasive-species. Accessed 10 Nov. 2023.

Zhou, Youbing, et al. “Spatial organization and activity patterns of the masked palm civet (Paguma larvata) in central-south China.” Journal of Mammalogy, vol. 95, no. 3, 26 June 2014, pp. 534-542.