| Creator | Søren Solkær |

| Media Form | Photograph |

| Genre | Nature Photography |

| Technique | [need to find interview or get book, Black Sun] |

| Date and Location of Creation | 2017-2022, Europe |

| Publication Information | Image included on webpage featuring interview with Solkær |

| Invasive Species Represented | European Starling, Sturnus vulgaris (“invasive” in the US) |

This summer, as I was planning to teach this course, a friend of mine was battling Asian jumping worms in her garden beds. She explained that unlike the earthworms we grew up appreciating for aerating the soil, these jumping worms were doing damage and she was doing everything possible to eliminate them. They had come into her yard in the mulch she purchased from a garden center, and she was trying to bag them up before they were able to reproduce and get established in her soil. Because I’m oblivious when it comes to gardening, I asked lots of annoying questions: How much damage could these worms actually do? If they were already in the area, was it reasonable to expect to be able to eliminate them from her yard? Because I was also preparing to teach this class, I thought of the image and description on the website she pulled up as a representation worthy of careful analysis. While these are not the only non-native earthworms and it is not yet clear what harm they will do, readers are being encouraged to eliminate them as soon as possible.

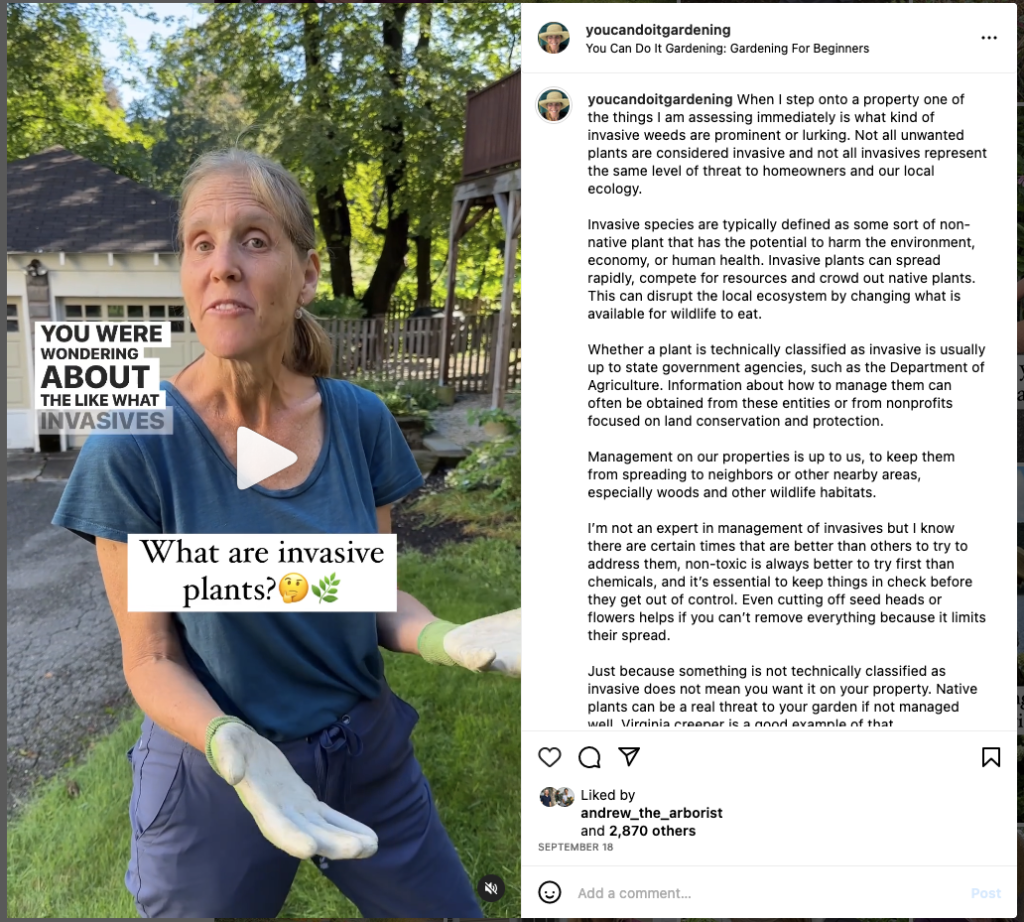

Now, I have a yard filled with so-called invasive species and I don’t have a clue what to do about them. I’ve started following a few Instagram accounts about gardening with native plants and here the advice is much the same as with the jumping worms. It’s going to be hard, but you need to get rid of invasives quickly. This is what Jess (@youcandoitgardening) shares, as she explains to one of her clients what invasives are (click the link to watch the reel; I can’t figure out how to embed Instagram reels):

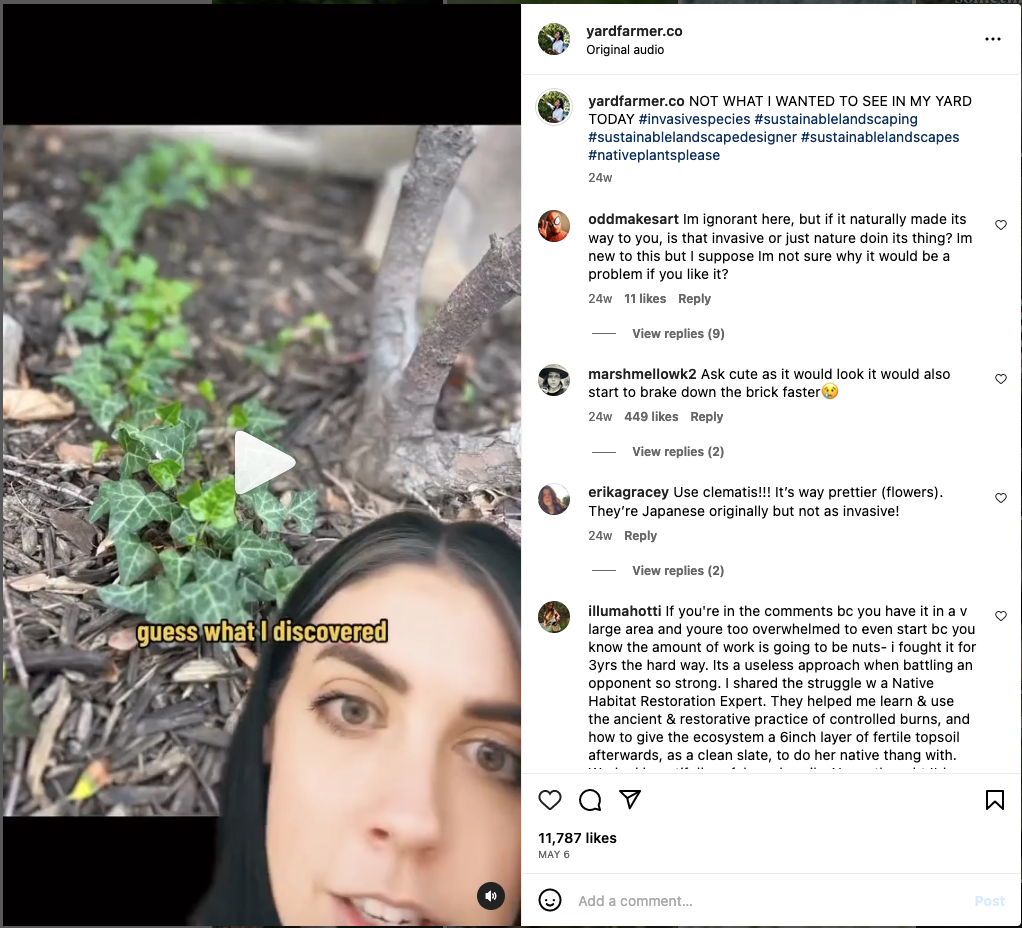

And it’s also what Daryl (@yardfarmer.co) explains in her post lamenting the discovery of English Ivy on her property.

The trend across these Internet publications about invasives is a single story: an invading force is going to destroy the harmony that existed before it arrived. Before thinking about representations of nature as closely as I have for this class, I didn’t have a problem with this story when it applied to jumping worms, or Virginia creeper, or English ivy, but in the context of this course something about it felt familiar–and unsettling. It sounded a little bit like xenophobia. I realized that I had questions about the way we talk about invasive species, which meant that I was going to need to learn more about invasion biology. What I discovered was pretty fascinating. I encourage you to read this post and select one of the sources I cite to read fully before class on Monday. Please select a specific passage (2-3 sentences or so) from the source you read carefully and come to class ready to share your response to that passage.

What Is An Invasive Species?

In his famous 1958 book, The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants, Charles Elton explains that “silent explosions,” resulting from invasion by a foreign species are “commoner in our lives than they were in the last century” because “We are living in a period of the world’s history when the mingling of thousands of kinds of organisms from different parts of the world is setting up terrific dislocations in nature” (18). He makes it abundantly clear that the recent second world war and the man-made explosions that horrified the world inform his understanding of how species were spreading beyond their native ranges.

In his introduction to the 2011 book Fifty Years of Invasion Ecology: The Legacy of Charles Elton, David M. Richardson explains that the field has grown and evolved since Elton’s book was first published, with scientists focusing on the “interactions between escalating invasions, other facets of global change, and changing paradigms in ecology, environmental management and ethics, and conservation.” He also notes that there are critics of the approach:

It also has its antagonists and naysayers: those who believe, for instance, that labelling an organism as non-native, trying to keep such organisms out and seeking to eradicate them once they have arrived (even when they have been shown to cause damage) is akin to xenophobia and that this has no place in our homogenized world where diversity of people, cultures, cuisines, etc. is often seen as desirable.

David M. Richardson, Introduction to Fifty Years of Invasion Ecology

While I wouldn’t say that Richardson’s characterization of the beliefs of the “antagonists and naysayers” quite captured the things I was noticing, it was helpful to note that I was not alone in recognizing a commonality in the fear of so-called “invasive species” like jumping worms and the fear of so-called “illegal immigrants.”

It’s helpful, I think, to look back at the way Elton describes invasive species in his seminal book. Take, for example, his description of the invasive diseases that killed native plants:

At the beginning of this century sweet chestnut tree in the eastern United States began to be infected by a killing disease caused by a fungus, Endothia parasitica, that came to be known as the chestnut blight. It was brought from Asia on nursery plants. In 1913 the parasitic fungus found its natural host in Asia, where it does no harm to the chestnuts. But the eastern American species, Castanea dentata, is so susceptible that it has almost died out over most of its range […] So far, the only answer to the invasion has been to introduce the Chinese chestnut, C. mollissima, which is highly though not completely immune through having evolved into the same sort of balance with its parasite, as had the American trees with theirs; much as the big game animals of Africa can support trypanosomes in their blood that kill the introduced domestic animals like cattle and horses.

Charles Elton, The Ecology of Invasions by Plants and Animals, 21-23.

It’s interesting to me that a solution to the blight on native chestnut trees is to bring in the Chinese chestnut, which is more resistant to the fungus. There was no chance of fighting the fungus, but chestnut trees are desired–so a non-native species is imported.

The Case of the European Starling

Elton’s book offers many examples like the chestnut blight. Another fascinating example comes in the form of the European starling. Elton explains that “a stock of about eighty birds” were “put into Central Park, New York” in the late nineteenth century and now the birds exist all over North America, from Mexico to Alaska, and as far west as a line running southward from Lake Michigan (24).

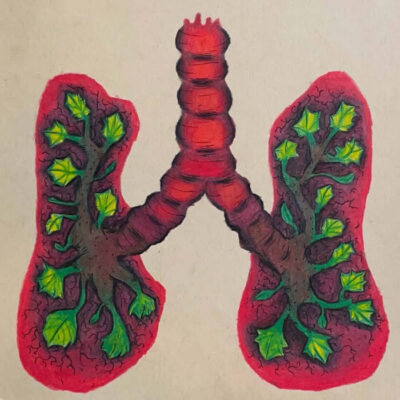

My featured image from this post was produced by a Danish photographer, Søren Solkær, who follows European starlings on their winter migration to capture their beautifully coordinated “murmurations.” These birds inspire wonder in the human beings that observe their behavior. In a fascinating interview with WBUR’s Here and Now, he even describes a woman observing their flight bursting into tears (3:25).

This photographer’s work focuses entirely on the magnificence of starlings, which makes sense because they are European starlings and he is photographing them in Europe. I wanted to know why starlings were first brought to the United States and if/how their importation has had a negative impact. The initial source I found suggested that it was a particular man who brought them to Central Park because he was obsessed with Shakespeare and wanted all of the birds mentioned by the beloved author to be in North America.

I kept hunting for more details about this claim (it’s actually mentioned briefly at the start of the interview above!) and eventually found an article published in Environmental Humanities that argues that it is an urban legend (and a very convenient one at that). It’s much better to read the article in full, but a summary of the argument is that the not-very-true story of how starlings were brought to the US makes it easier to suggest that their introduction is the result of human folly and that they’re doing major damage to our ecosystems. This interpretation of starlings as a dangerous invasive species is encouraged by the agriculture industry–most specifically large factory farms that have invested significant money in poisoning starlings that steal feed from cattle.

I quote here the most pertinent finding from the article for my purposes in this post:

The story template of the introduced animal or plant upending an ecosystem remains widespread among environmentalists today, where it is used to drive home the dangers of invasive species—a common but increasingly controversial term that has been institutionalized in US law since the 1990s.30 While introduced species do sometimes naturalize, very few imports pose a threat to native populations; a common estimate holds that only about 1 percent of introduced species cause significant problems.31 Furthermore, predicting invasiveness based on species characteristics has proven difficult, leading some scientists to believe the success of an introduction has less to do with the species than with the invasibility of the ecosystem it enters.32 A number of studies even indicate that successful nonnative species can add to biodiversity without driving indigenous species to extinction.33

Lauren Fugate and John MacNeill Miller, “Shakespeare’s Starlings: Literary History and the Fictions of Invasiveness”

I also learned, by reading this article, that the same nagging sense I had that something is influencing the way we talk about invasive species seems to have inspired Ursula K. Heise’s approach in Imagining Extinction: The Cultural Meanings of Endangered Species. In this book, Heise explores the “human stories that frame our perception and relation to endangered nonhumans” (5). In her introduction, she asks a series of questions that I am finding helpful as I think about invasives (so I’ve inserted in brackets my own language):

How, when, and why do we invest culturally, emotionally, and economically in the fate of threatened [or invasive] species? What stories do we tell, and which ones do we not tell, about them? What do the images that we use to represent them reveal, and what do they hide? What kind of awareness, emotion, and action are such stories and images meant to generate? What broader cultural values and social conflicts are they associated with?

Ursula K. Heise Imagining Extinction: The Cultural Meanings of Endangered Species, p. 5

What I was noticing in the warning about invasive worms is that it had a lot in common with the way some Americans talk about the immigration of humans from neighboring countries. I don’t think this is always deliberate, and I don’t think I’m fully able to articulate why that matters yet, but I’m hoping our discussion in class will help me figure it out.

Should We Stop Thinking in Terms of Native vs. Invasive?

It’s important to note that it is not just scholars in the humanities who have critiqued the way we talk about invasive species. In his article for Nature, Mark A. Davis argues that land managers and policy-makers need to move beyond the “native-alien” dichotomy:

Today’s management approaches must recognize that the natural systems of the past are changing forever thanks to drivers such as climate change, nitrogen eutrophication, increased urbanization and other land-use changes. It is time for scientists, land managers and policy-makers to ditch this preoccupation with the native–alien dichotomy and embrace more dynamic and pragmatic approaches to the conservation and management of species — approaches better suited to our fast-changing planet.

Mark A. Davis et. al. “Don’t Judge Species on their Origins”

His article, co-authored with 18 ecologists who share his perspective, outlines the history of the concept of “nativeness,” explaining that it was first introduced in 1835 by John Henslow, an English botanist. Davis further explains that while the terms “native” and “alien” had been adapted from common law by the 1840s to describe species they were studying, there wasn’t a consensus among scientists about what should be done even when Charles Elton wrote his famous book in 1958, The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants.

He goes on to explain that the classification is itself unhelpful:

Nativeness is not a sign of evolutionary fitness or of a species having positive effects. The insect currently suspected to be killing more trees than any other in North America is the native mountain pine beetle Dendroctonus ponderosae. Classifying biota according to their adherence to cultural standards of belonging, citizenship, fair play and morality does not advance our understanding of ecology. Over the past few decades, this perspective has led many conservation and restoration efforts down paths that make little ecological or economic sense.

Mark A. Davis et. al. “Don’t Judge Species on their Origins”

Are Humans an Invasive Species?

If you, like me, had this thought at any point while reading this post, I encourage you to check out this article in the Smithsonian Magazine. It’s actually a bit complicated and provides as useful reminder that humans: 1) classify species, 2) transport species deliberately, and 3)categorize them as invasive in specific regions.

Works Cited

Davis, Mark A., et al. “Don’t Judge Species on Their Origins.” Nature, vol. 474, no. 7350, June 2011, pp. 153–54. www.nature.com, https://doi.org/10.1038/474153a.

Elton, Charles S. (Charles Sutherland). The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants. London : Chapman & Hall ; New York : distributed in the U.S.A. by Halsted Press, 1977. Internet Archive, http://archive.org/details/ecologyofinvasio0000elto.

Fugate, Lauren, and John MacNeill Miller. “Shakespeare’s Starlings: Literary History and the Fictions of Invasiveness.” Environmental Humanities, vol. 13, no. 2, Nov. 2021, pp. 301–22. Silverchair, https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-9320167.

Knauss, Nancy. Look Out for Jumping Earthworms! https://extension.psu.edu/look-out-for-jumping-earthworms. Accessed 27 Oct. 2023.

May 6 post. Instagram. Directed by @yardfarmer.co, 2023, https://www.instagram.com/p/Cr59LoHLaWA/

Richardson, David M. “Introduction.” Fifty Years of Invasion Ecology, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2010, pp. i–xix. Wiley Online Library, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444329988.fmatter.

September 18 post. Instagram. Directed by @youcandoitgardening, 2023, https://www.instagram.com/reel/CxVS1wyu_Ln/.

Young, Robin. “Beautiful, Dramatic and a Little Bit Scary”: Danish Photographer Captures Starling Murmurations. https://www.wbur.org/hereandnow/2022/06/13/soren-solkaer-starling-murmurations. Accessed 27 Oct. 2023.

Zielinski, Sarah. Are Humans an Invasive Species? | Science| Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/are-humans-an-invasive-species-42999965/. Accessed 28 Aug. 2023.