| Creator | Laurie O’Keefe |

| Media Form | Artwork |

| Genre | Natural Science |

| Publication Information | Currently available for purchase at Science Photo Library |

| Species Represented | Miacis -> Canis Lupus (Dog) |

Dogs: man’s best friend. But how did it come to be that way? Well, let’s talk about evolution.

First, let’s get some misconceptions out of the way. Evolution does not have a goal or a purpose, it just happens. Nature is not “selecting genes” for anything. When a mutation happens, it either gets entered into the gene pool or that plant/animal/etc. fails to reproduce. That’s not always survival of the fittest–sometimes that’s survival of the most attractive, or survival of the one who happened to be around, or survival of what seemed best in that moment but in hindsight was a really bad option. If it works, and it reproduces, then it goes on. Furthermore, individuals don’t evolve, populations do. What that means is that while an individual might have a genetic mutation, it is the reproducibility of that mutation that results in lasting change.

But that might lead to some confusion. If one member of a group of animals is born with lighter fur and goes on to form a whole group in one area that has lighter fur, does that mean that there is now a new species hanging around? Well, no. Usually there is some cross-compatibility that muddies the waters, so to speak. The most commonly used definition of species refers to the biological species concept, which essentially means a species is a reproductive community which shares a common gene pool. For this example, the animals with lighter fur are still within the reproductive community. However, B. N. Singh states that “The biological species concept is the most widely accepted, but there are three main difficulties in its application: insufficient information, uniparental reproduction and evolutionary intermediacy” (786). Insufficient information can be solved with thorough studying of lineages. Uniparental reproduction, while immensely interesting, will not be discussed within this post. But what is most interesting is the “difficulty in the application of biological species concept in those situations in which speciation is incomplete” (Singh 787). For example: dogs.

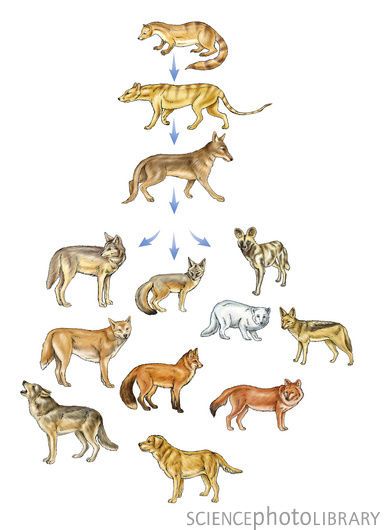

What the above image does a spectacular job of showing via the loss of arrows as the chart flows downwards is that the lines of evolution become blurry as time moves onwards. There are today many wolf-dog hybrids, communities of dog-coyote hybrids, coyote-wolf hybrids, etc. According to Robert K. Wayne, “Wolf-like canids can travel great distances and overcome size-able topographic obstacles.

Gray wolves, for example, have been observed to disperse over a thousand kilometers during their lifetime. Because dispersing wolves may establish territories and reproduce, gene flow can occur over much larger distances than is usual for terrestrial vertebrates” (221). Because of this, and the phylogenetic similarities between wolf-like species referenced in Wayne’s article, a lot of populations of these animals cross paths. Subsequently, and of course due to some other nuanced influences, “coyotes and wolves had hybridized in areas of eastern Canada where wolves were rare and coyotes common” (Wayne 223). There are plenty of questions surrounding the extent to which these hybridizations are the case, but for now let’s focus on the idea that there is more variety out there than just “wolf” and “coyote”, and it seems to go without saying that there exists plenty of variety in “dogs”.

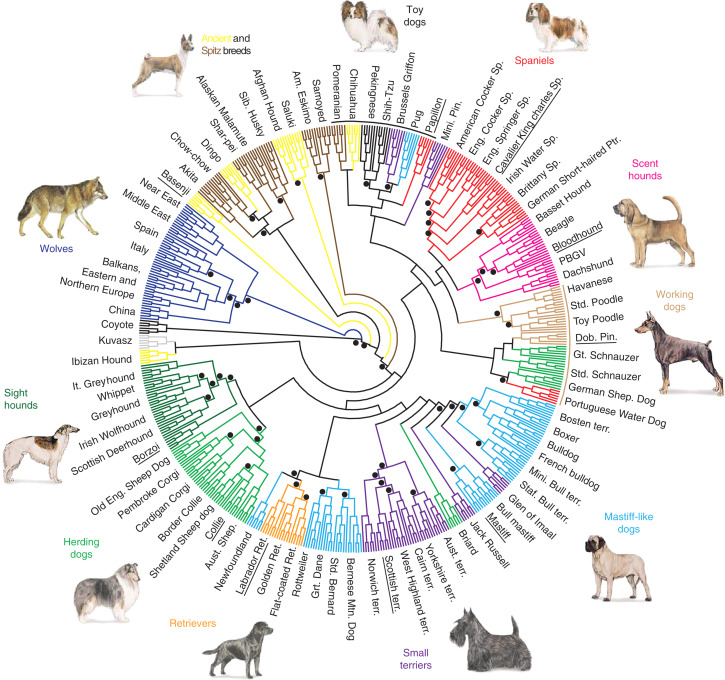

The above image acts as something of a family tree (which happens to be missing most of the information regarding the branches). The family in question is dogs, with the outermost branches representing dog breeds. But what is at the center? Well, as Laurie O’Keefe’s image depicts, the tree would eventually lead us to an ancient ancestor of carnivorans called Miacis. After that, the branches get increasingly complicated and lead down to coyotes, wolves, jackals, and plenty of other animals outside of the scope of this post. Then, obviously to dogs, right? As we’ve already figured out, it’s a bit more complicated than that.

While you might have heard the story that humans brought ancient wolves into their settlements, “early domestication was driven by wolves for scavenging benefits” (Power 372). Not only did dogs adopt us, but they seemed to do so many times over. According to Wayne, the remains of the earliest known dogs (10-15 thousand years old) suggests “multiple domestication events at different times and places” (220), which means that where there were both gray wolves and people, there was bound to be a friendship brewing.

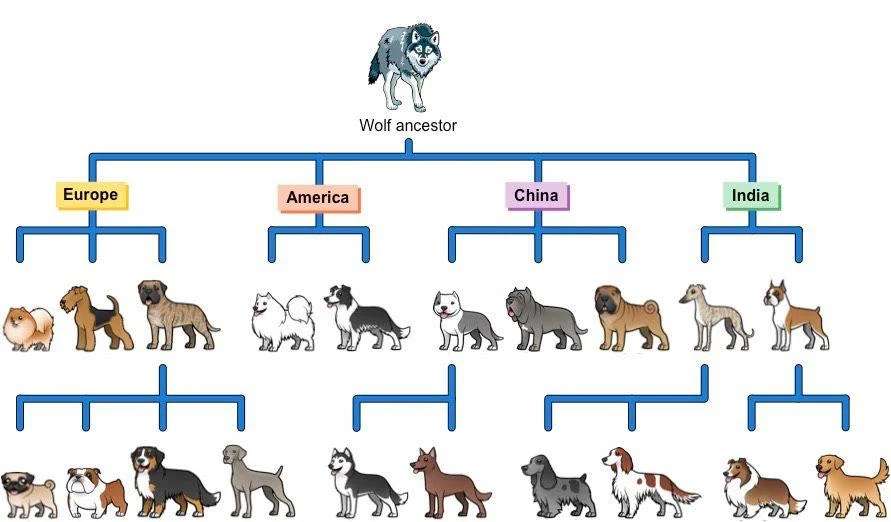

From there, we start to see selective breeding, which acts differently than evolution in nature because we introduce artificial selection. Now, variations in generations can be actively chosen as they are encountered, and made to enter populations at a much faster rate. Next thing we know, I’m growing up with two golden retriever/cocker spaniel mixes named Echo and Trouble and a husky mix named Maggie (and you could really see the wolf in her), and countless families around the world are warming their homes with fluffy friends.

The above image shows, very broadly, some dog breeds and where in the world they originated. The variation is astonishing! Yet genetically, gray wolves and dogs are almost exactly the same (Wayne 220). With that in mind, alongside the knowledge that hybridization between wolves and dogs is common, it could be easy to jump to the conclusion that wolves and dogs are the same species. The struggle to define species leads to some complicated thoughts on the line between dog and wolf, or really even what a breed is. Breeds undoubtedly hold behavioral and phenotypical variation, but if they are so similar to wolves, who is to say that your pug isn’t really a fearsome (if goofy) beast?

All I can say for certain is that I am grateful to Miacis for fostering the evolutionary changes that led to the wolf. I am grateful for the wolf for choosing humans, again and again. I am grateful for our human ancestors for taking them in. I am grateful for all the choices that led to my girl Echo staying with us for 13 incredible years. In science, all sorts of definitions are ever-changing and flexible, leading people like me to come in with a thousand questions and leave with a thousand more. But one thing is for certain: we are lucky to have these incredible creatures by our side.

And, of course, after all this, I can’t forget to mention that dogs are called Canis Lupus. And so are wolves.

Works Cited

Power, Emma R. “Domestication and the Dog: Embodying Home.” Area, vol. 44, no. 3, 2012, pp. 371–78. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23251559. Accessed 4 Oct. 2023.

Singh, B. N. “Concepts of Species and Modes of Speciation.” Current Science, vol. 103, no. 7, 2012, pp. 784–90. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24088835. Accessed 4 Oct. 2023.

Wayne, Robert K. “Molecular Evolution of the Dog Family.” Trends in Genetics, vol. 9, issue 6, 1993, pp. 218-24. Science Direct, www.cell.com/trends/genetics/pdf/0168-9525(93)90122-X.pdf. Accessed 6 Oct. 2023.

Further Reading:

Savolainen, Peter, et al. “Genetic Evidence for an East Asian Origin of Domestic Dogs.” Science, vol. 298, no. 5598, 2002, pp. 1610–13. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3832846. Accessed 6 Oct. 2023.

Leonard, Jennifer A., et al. “Ancient DNA Evidence for Old World Origin of New World Dogs.” Science, vol. 298, no. 5598, 2002, pp. 1613–16. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3832847. Accessed 6 Oct. 2023.