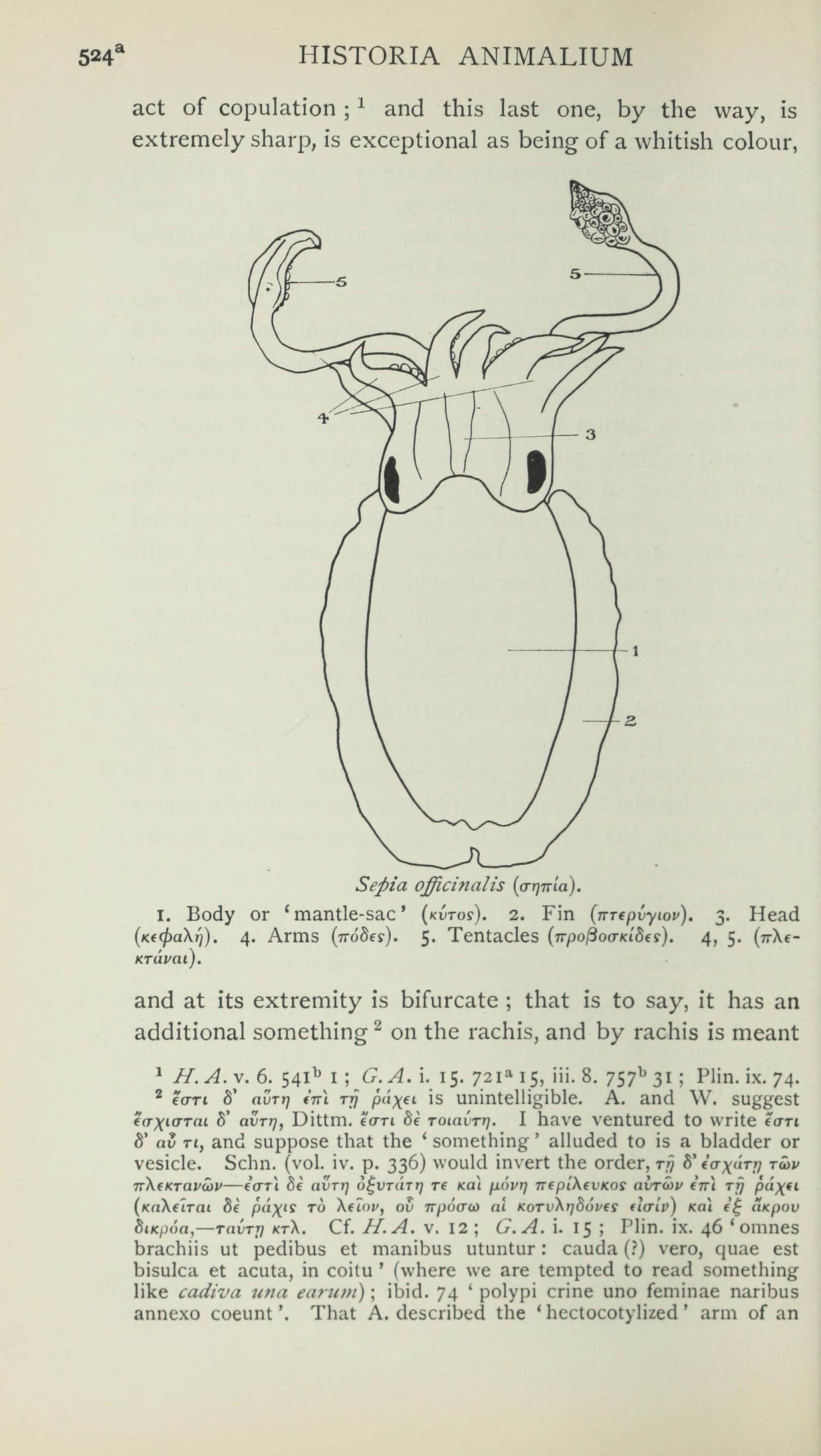

As we begin our unit on species, I want to look at the earliest known representation of nature that attempts to establish distinct species. According to our current understanding (which is imperfect, because it can only be built around writing that survives from ancient civilizations), Aristotle was the first to classify the natural world. He divided it into plants and animals. The image I have featured in this post is from a 20th-century translation of his Historia Animalium, which is dated to the fourth century, BCE. We can’t see the original pages of this work, but scholars over many centuries have created copies and translations. The English translation that D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson published in 1910 offers remarkable insight into our earliest record of the human attempt to classify other living things (and the later human attempt to correct and clarify those other classifications).

Most of the page includes notes about how other scholars have interpreted the fragment of Aristotle’s text to understand his meaning. Through all this, we see observations about the parts of the animal. If you were to search the name given in this English translation, it is the same binomial name—Sepia officinalis—used today for the common cuttlefish. When I saw this, at first I wondered if that was a translation of the name Aristotle gave to this organism in the original Greek. If yes, this would mean that the names Aristotle gave to species survive to this day. BUT…it turns out that this name (and, actually, the entire illustration) is supplied by the translator. In his book The Lagoon: How Aristotle Invented Science, Armand Marie Leroy explains (with affection) that “Thompson applied his zoology to identifying the creatures that Aristotle described” (13). Frustrated that a scientist in 1910 was adding his own terminology to his translation of an Ancient Greek text, I found a point of comparison–a translation published in 1933 by A.L. Peck. You can see roughly the same part of the text in the image to the left. Where Thompson says “In mollusks the external parts are as follows,” Peck translates the Greek as “The following are the external parts of the Softies as they are called.” I can’t assess whose translation is more accurate, but it is amusing to imagine Aristotle using a word that translates roughly as “softies” as he went about classifying living organisms. An an English professor who typically studies how texts change over time with each new edition or translation, it is fascinating to me that my attempt to understand how humans first started to make sense of other species requires navigating not just history, but also languages and techniques of translation over time. More than anything, my takeaway from this research is that human representations of nature, especially when they involve language, are incredibly complex!

Much has been said about the method Aristotle uses in this work and its relation to our current understanding of the scientific method. This methodology is explored and contextualized in James Lennox’s article for the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. I’ve spent more time with Aristotle’s Poetics, but it’s interesting to note that Aristotle is as curious about how story influences human experience as he is curious about how other living things interact and reproduce. Most important to me is the fact that Aristotle, a human with specific experiences and views of the world (for example, the endorsement of slavery), makes observations and classifies animals. We can’t perfectly know exactly how he did this because we don’t have a perfect record of what he wrote. Nevertheless, we know that he made classifications and I want to encourage you all to think of these as representations of nature (and foundational to the biological sciences).

I think often about how our human abilities of perception shape the way we classify the non-human world. Can humans make objective observations or do they find what they believe to be present? In medieval Christianity (closer to our own time but long AFTER Aristotle), living things were classified into the great chain of being. As you can see below, angels are at the top, and then humans, and then animals, and then plants, and then those poor minerals, that can’t move of their own volition.

And then, when Darwin was developing his theory about the origin of species in the nineteenth-century, he so wisely acknowledged that perhaps the idea of “species” was really just a result of the human desire to categorize. If we do not exist in a world in which a creator established a finite set of distinct species with particular characteristics (if, instead, species emerge from random mutations that prove more conducive to survival than existing traits) then what exactly is this thing called a species?

The famous evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould describes the situation in this way:

Common sense dictates that the world of familiar, macroscopic organisms presents itself to us in “packages” called species. All bird watchers and butterfly netters know that they can divide the specimens of any local area into discrete unities blessed with those Latin binomials that befuddle the uninitiated. […]This notion of species as “natural kinds” fit splendidly with creationist tenets of a pre-Darwinian age […] But how could a division of the organic world into discrete entities be justified by an evolutionary theory that proclaimed ceaseless change as the fundamental fact of nature? Both Darwin and Lamarck struggled with this question and did not resolve it to their satisfaction. Both denied to the species any status as a natural kind. Darwin lamented: “We shall have to treat species as…merely artificial combinations made for convenience.”

“A Quahog is a Quahog“

And yet, Gould explains, Darwin and Lamarck went on to name species and use existing classifications in their work. And we are going to dive into the world of species and debates about speciation (when and why species become distinct) in the coming weeks. We’re going to do that work by investigating representations of particular species that we find interesting. Before class, I encourage you to explore one very complex representation of species, which visualizes all species on earth over time, from the earliest bacteria to our closest relative, the chimpanzee. Please watch the video below introducing the Tree of Life and use the Tree of Life Explorer to play around.

Works Cited

Gould, Stephen Jay. “A Quahog Is a Quahog” The Panda’s Thumb: More Reflections in Natural History. New York: Norton, 1982. p. 204-205.

Leroy, Armand Marie. The Lagoon: How Aristotle Invented Science. Penguin: New York, 2015.

Peck, A.L. Historia Animalium. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1970.

Thompson, D’Arcy Wentworth. Historia Animalium. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1910.