| Creator | Evelyn De Morgan |

| Media Form | Oil Painting |

| Genre | Pre-Raphaelite Spiritualism |

| Technique | Oil on Canvas |

| Date and Location | 1880 England |

| Publication Information | A painting by Evelyn De Morgan signed in 1880, currently in the possession of the De Morgan Collection |

| Natural Phenomenon Represented | Death |

Death is a pretty common affliction—after all, it will happen to everyone. It is an unavoidable conclusion to our mortal lives, and is simultaneously unknowable. Human beings, and their tendency to obsess over that which they do not understand, are therefore obsessed with the idea of death. Time and time again it has been personified and depicted in various different ways. This painting by Evelyn De Morgan depicts death as a familiar reaper figure with traditionally angelic features like wings, who appears to be comforting the girl in the painting. De Morgan chose to place growing flowers at Death’s feet, which serves to emphasize the character’s benevolence.

So where did the Reaper come from? According to a Britannica article, the figure of the Grim Reaper originated around the same time as the Black Death. The scythe carried by this skeletal embodiment of death is an agricultural tool used to “harvest crops that were ready to be plucked from the earth” which ties into the idea that people were dying en masse, their souls being effectively plucked from the earth by Death. The image is a dark one: the character is typically a skeleton clothed in a long, black robe, often seen alongside other dead or dying imagery like the barren landscape in the background of De Morgan’s painting. De Morgan’s Death is not skeletal, but angelic, more closely akin to a religious symbol that was common of pre-Raphaelite artworks.

This era of artwork and those associated with it (known as the “Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood”, or PRB) created works which pushed back against many aspects of life and society which were common at the time, such as traditional ideas of femininity, traditionally indoor art teachings, and later the push towards industrialization. The movement greatly encouraged plein air painting, which is the practice of creating artwork in nature based on what is seen. The practice is still popular today! In this particular painting by De Morgan, the softness in the expression of the Angel of Death is accompanied by the growth of flowers at the character’s feet, along with the woman in the painting reaching out towards Death. This suggests that death is not a negative figure both for nature and for humanity. This is definitely in contrast with the fear that went alongside the Grim Reaper in earlier days, and follows the trend of this era of artists pushing back against traditional ideas.

But how do others view death? While I was thinking about the topic, I couldn’t help but be drawn to other examples which paint death in a positive light, or at the very least look at the concept with a perspective that expands upon the grim (no pun intended) outlook that stereotypically accompanies the idea. Next, I thought of Emily Dickinson’s “Because I could not stop for Death”.

Because I could not stop for Death –

He kindly stopped for me –

The Carriage held but just Ourselves –

And Immortality.

We slowly drove – He knew no haste

And I had put away

My labor and my leisure too,

For His Civility –

We passed the School, where Children strove

At Recess – in the Ring –

We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain –

We passed the Setting Sun –

Or rather – He passed Us –

The Dews drew quivering and Chill –

For only Gossamer, my Gown –

My Tippet – only Tulle –

We paused before a House that seemed

A Swelling of the Ground –

The Roof was scarcely visible –

The Cornice – in the Ground –

Since then – ’tis Centuries – and yet

Feels shorter than the Day

I first surmised the Horses’ Heads

Were toward Eternity –

| Creator | Emily Dickinson |

| Media Form | Poetry |

| Genre | Rhymed Free Verse |

| Date | ~1863 |

| Publication Information | Originally published posthumously in 1890 in “Poems” by Roberts Brothers of Boston |

| Natural Phenomenon Represented | Death |

This poem by Emily Dickinson takes another approach to creating a personified Death. Written in quatrains, the poem depicts the speaker’s journey into the afterlife as accompanied by Death. She used plenty of traditional poetic devices like alliteration and rhyme, but also capitalized specific words to draw attention to them. Like De Morgan’s painting, Dickinson’s poem has a positive view of death, showing the character to be leisurely and patient, and ending the poem with a dash rather than a period to signify that death did not lead to the end. I was especially struck by the shared feeling between the two creators that death seemed to be familiar and trusted.

What about depictions of death that aren’t personifications, however? At first, I was a bit stumped on this one. Most of the examples I could think of off the top of my head were more focused on the grief of those left living, or grief in general. While I don’t think it is a feeling to be ignored, I do feel it is worthy of its own blog post, and is certainly not something I am ready to cover here. But another example did occur to me: the 2018 film Annihilation.

| Title | Annihilation |

| Director | Alex Garland |

| Media Form | Film |

| Genre | Sci-Fi |

| Date | 2018 |

| Released By | Paramount Pictures |

| Natural Phenomenon Represented | Death |

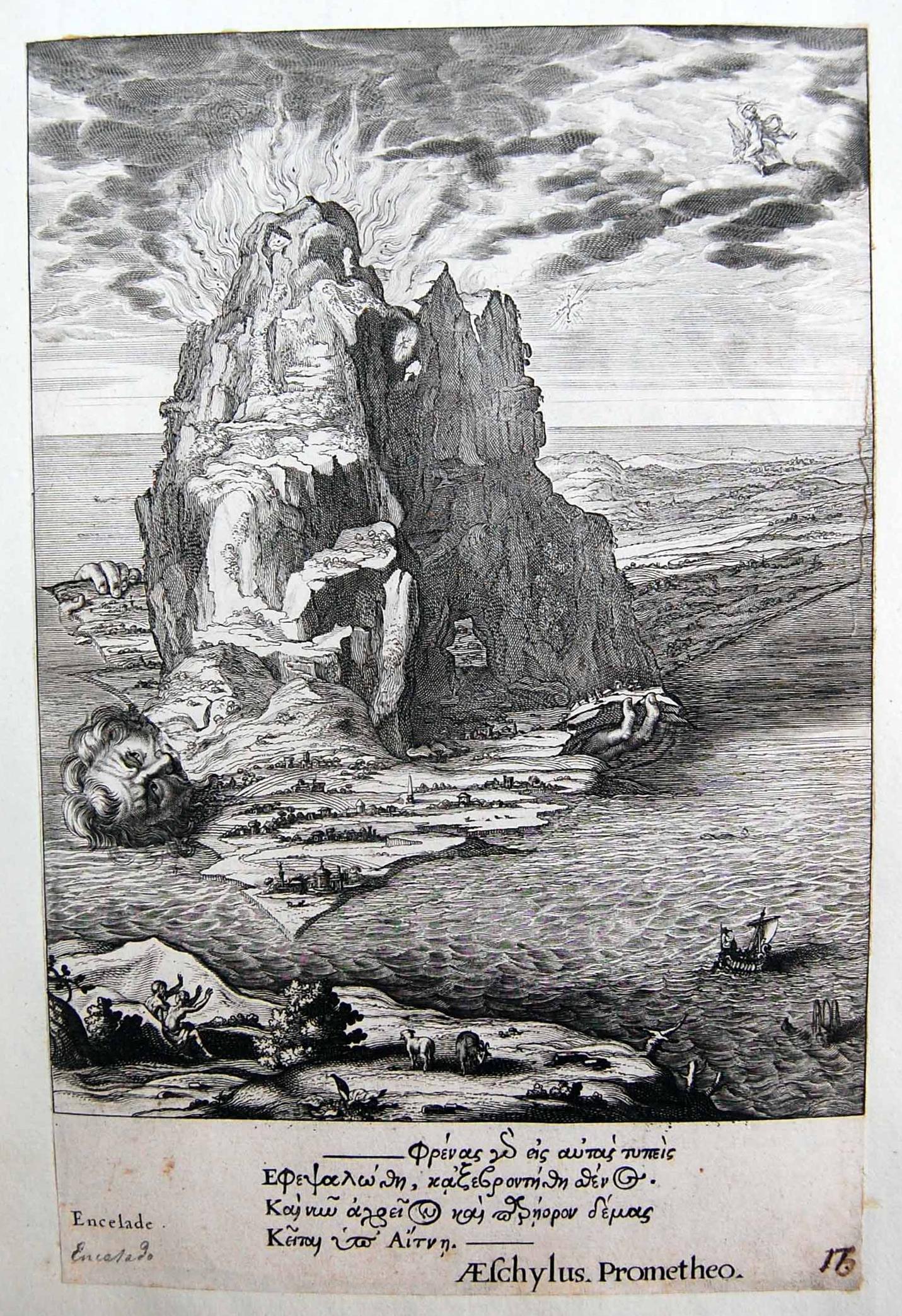

Annihilation, a 2018 film (based on a book by Jeff Vandermeer), takes a unique look at many things–death included, and this time, not personified. Apologies for spoilers, but throughout the film there are many characters that die. These are not always traditional deaths: one character becomes a sort of human-shaped plant, reminiscent of a nymph. In this image, a character who died off-screen morphed into this fungal/plant/skeletal thing (for lack of a better word). The emphasis in this film was on a sort of refraction of existence that merged things together in strange, sometimes beautiful, sometimes terrifying ways. While some were focused on the more brutal aspects of this scene, I was especially struck by this moment in the film because I thought it was an absolutely stunning and unique representation of death. The body is split into two parts: one sits where it originally died, and one reaches upwards and outwards as it cries out. What is more beautiful than the merging point of life and death, and wondering what lies beyond?

There are so many ways to think about death, and I have been repeatedly amazed by the search for safety, growth, and meaning in an unknowable idea. With enough time, I could find dozens more examples of how people face the idea of mortality. Hopefully, we can share the love that pours out of the examples shared here today.