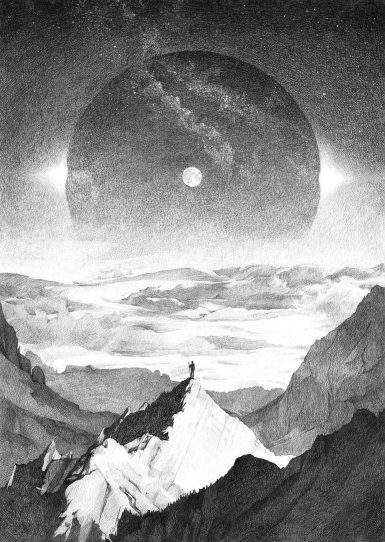

| Creator | Takahashi Masumi |

| Media Form | Digital Upload of Photo |

| Genre | Landscape |

| Technique | Photography |

| Creation Date and Location | Winter of 2021 or 2022 Hokkaido, Japan |

| Publication Information | Released as a part of Japanese PR Office’s collection titled “Japan’s ‘Snow Country’” in January 2022 |

| Natural Phenomenon Represented | Diamond Dust |

Dancing through the wind, whispering to those caught in the glimmering fog in the region of Hokkaido, Japan, photographers such as Takahashi Masumi stand within winter phenomenon, capturing photos to share across the globe. This event is known as diamond dust, and while it occurs across the world, Japan seems to hold a unique appreciation and fascination with the crystalized performers. While not as widespread as, for example, Mount Fuji, or as well known of a phenomenon as tsunamis or earthquakes, diamond dust seems to sneak its way into various artistic mediums originating from Japan. Some utilize diamond dust to portray a unique beauty, one rarer than the typical culprits of winter scenery, snow, ice, hail, etc. While others prefer to use diamond dust as the title of attacks, possibly hinting at the ferocity winter offers through it’s alabaster beauty.

I find it pertinent to note where I first heard of the phenomenon. Despite being raised almost exclusively in the Northeast, I didn’t and don’t believe I have seen diamond dust in person. So the first, and main example that creeps into my mind, was a piece of Japanese media that exploded in popularity in France and Brazil, the latter being where my father was raised. This series goes by the name Saint Seiya: Knights of the Zodiac, an anime released in the late 1980’s. Through the blessing of the cosmos, and amplified by armor representing various constellations, certain fighters would utilize ice in combat. The main examples that come to mind are the representatives of Aquarius and Cygnus, the water jug and swan, a master and his student. Though (very) dated and naturally over the top, Saint Seiya‘s portrayal of diamond dust paints it with a special sense of power and grace. The users of the technique are typically associated with a refined elegance, while the actual ice crystals are strong enough to break apart armor, and even freeze entire individuals. This portrayal is the earliest representation of diamond dust in Japanese media I could find, though it is still a fascinating one as it establishes a decent baseline on what will follow in other Japanese art forms moving forward.

What’s intriguing is how diamond dust typically sneaks its way into two different mediums when shipped from Japan. The more mainstream method is through photography, where plenty of Japanese photographers present diamond dust, along with adjacent phenomenon such as sun pillars and sun halos. Takahashi Masumi even stated in his interview how he “[hopes] many people in Japan and overseas will visit Hokkaido and enjoy its unique winter scenery for themselves. ” While all these different tricks of moisture, light, and reflections can be found in other snowy areas, there’s some deeper fascination or meaning that seems to be gifted to Japan’s winters, perhaps tracing back to Shinto belief that every phenomenon of nature, element, and being has a kind of spirit, a piece of “godhood”, regarded as kami.

Some references to diamond dust in media even gives the event a connection to other Gods. Video games, specifically those under the Roleplaying (RPG) genre, seem to employ the name and imagery of diamond dust for the most powerful ice moves a player may access. The long running Final Fantasy series has likely the most frequent use of the phenomenon, where players can summon Shiva, of course notably named after the Hindu god. Though throughout the series, Shiva is instead portrayed as an ice-elemental goddess, and is for most entries, the only individual who can use the attack referred to as “Diamond Dust.” What’s interesting here is the difference in how the attack is shown off. Final Fantasy III or Final Fantasy VI showcase diamond dust as a barrage of tiny ice crystals, more akin to what the real life counterpart would look like, though naturally exaggerated. Yet other entries, such as Final Fantasy IX, showcase diamond dust as a more generic massive ice move, where a target is encased in a large ice structure before exploding. This latter portrayal happens in other RPGs as well, such as the Persona series. A question is then raised, did games like 3 and 6 use diamond dust as a basis for what the move would be, a small flurry of ice crystals, and try to provide a semi-accurate visual? If the answer is yes, then did other entries such as 9 just use the name because it simply sounds grandiose, to the point where they almost drop the “dust” part of the name entirely in exchange for a massive spectacle?

While I don’t want to believe this phenomenon is seen as (in)frequently just due to its name and not the actual beauty of its reality, that conclusion seems difficult to avoid for most of Japan’s representations of it. Plenty of Japanese media, especially in the more “nerdy” spaces, pull English terminology seemingly for dramatic purposes or bolstering international appeal. Thus, the implied beauty of shimmering dust, as hard and valuable as a diamond, might not have some deeper cultural value, and is just a tool to express graceful combat. The only other explanation could tie back to Shintoism, and trying to attribute a certain kind of mysticism to diamond dust, hence why it’s typically seen used by powerful figures, such as in Final Fantasy, or tied to universal forces, which is the case in Saint Seiya.

However, there is one series that utilizes diamond dust, not as an attack, not in any harmful way, but rather as the sight of beauty that it’s referred to as by photographers globally. This series is the highest-grossing video game franchise, an absolute titan in media, Pokémon. On a blog post in 2008, series director Junichi Masuda asked players to play Pokémon Diamond and Pearl on January 12th. Though possibly noticed previously, as said games released in 2006, this post made many boot up and explore the games, realizing that in the northmost area, in Snowpoint City, the usual snowy graphics were replaced with glimmering pixels. This change in weather was tied to real life events, as January 12th was Junichi Masuda’s birthday. Other dates also led to diamond dust falling, such as February 29th, just to make a leap year appear all the more special. Subsequent games also had their own days where winter regions would be blessed with the frolicking crystals, some days having possible references, such as the birthday of the anime protagonist’s voice actor. While the inclusion could be due to graphical advancements, it’s more likely due to how the Sinnoh region, where the player spends the game, is assumed by many to be based on Hokkaido. Thus, it’s made rather apparent that to the developers, diamond dust was an essential part in capturing the essence Hokkaido’s unique winter seasons.

While it is refreshing to see diamond dust portrayed in such a pivotal franchise in a more positive regard, where it’s present simply for its beauty, Pokémon makes it even more a positive force. In the games, prior to more recent entries, snowy conditions typically affected battles, where chip damage was dealt to the player and their opponent due to hail. However, diamond dust’s presence overrides snow in the overworld, and in battle. So diamond dust isn’t simply a trivial change of visuals, but is a force that assists the player, and has actually been applied to certain restricted playthroughs of the games where hail damage can be problematic.

With that view of Pokémon’s diamond dust concluded, that’s unfortunately the last notable instance of diamond dust that can really be explored in media that isn’t just photography or video. Other instances, such as a title from a 1960’s episode of Spider-Man, or as an area name in Sonic 3D Blast, are simply using the name to refer to an actual diamond and just denote a snow stage respectively. While there wasn’t more to discuss, I still assert that that there’s more to diamond dust and it’s importance to Japanese culture, specifically in the region of Hokkaido. Without being able to discuss the phenomenon with locals, or read Japanese texts that might provide more insight, there’s not much else to document, but I still find it’s sparse appearances from Japanese media fascinating. Hokkaido as a region clearly values the winter, as cities such as Sapporo have been celebrating winter festivals since 1950, even hosting the Olympics in 1972. I’d love to find out more from those in Hokkaido, or even just find more reliable translated texts that document the culture that sprouted in the region or allusions to the phenomenon. But until then, I’ll wait with bated breath for frigid temperatures and escalating humidity, where the wonder of diamond dust and the wonders of light it creates can be witnessed with appreciation.