Blues music and all of the music that has derived from it is inseparable from its history. Sharecroppers and Southern laborers are the forefathers of the blues, a music with its roots trailing back to the work songs of enslaved African Americans on Southern plantations during the 1800s. Mance Lipscomb was one of these sharecroppers, and his musical contributions to the genre made him one of the most influential blues musicians of his time.

Originally recorded by nearly 30 years after it was written, “Tom Moore’s Farm” by Mance Lipscomb is an acoustic blues song that highlights not only the musical tradition of the blues, but the history of Texas itself.

About the Artist

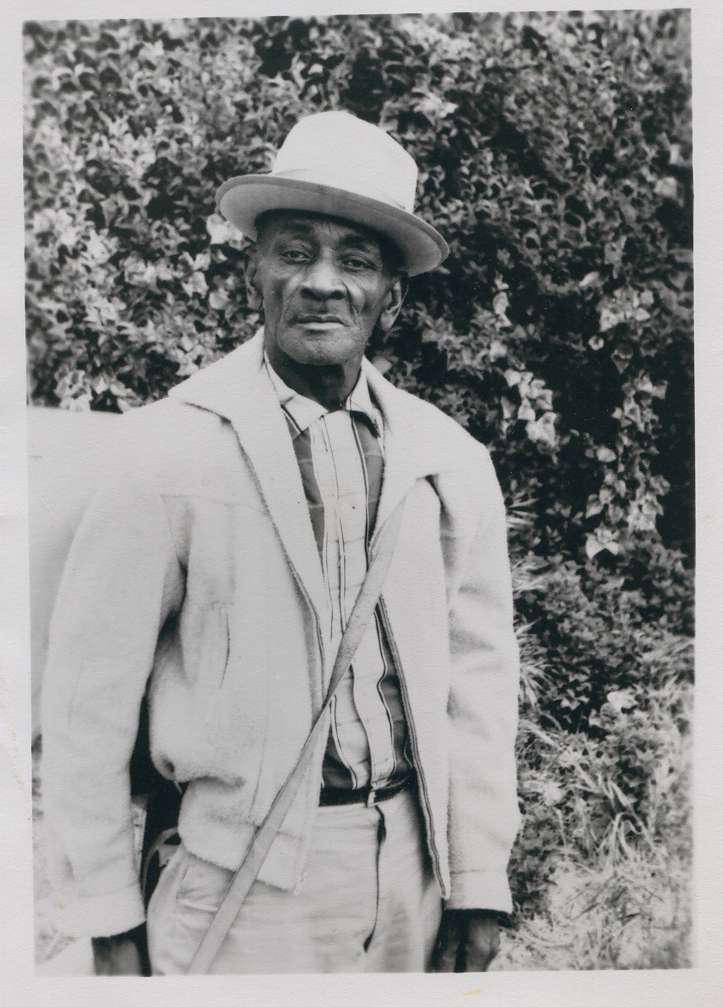

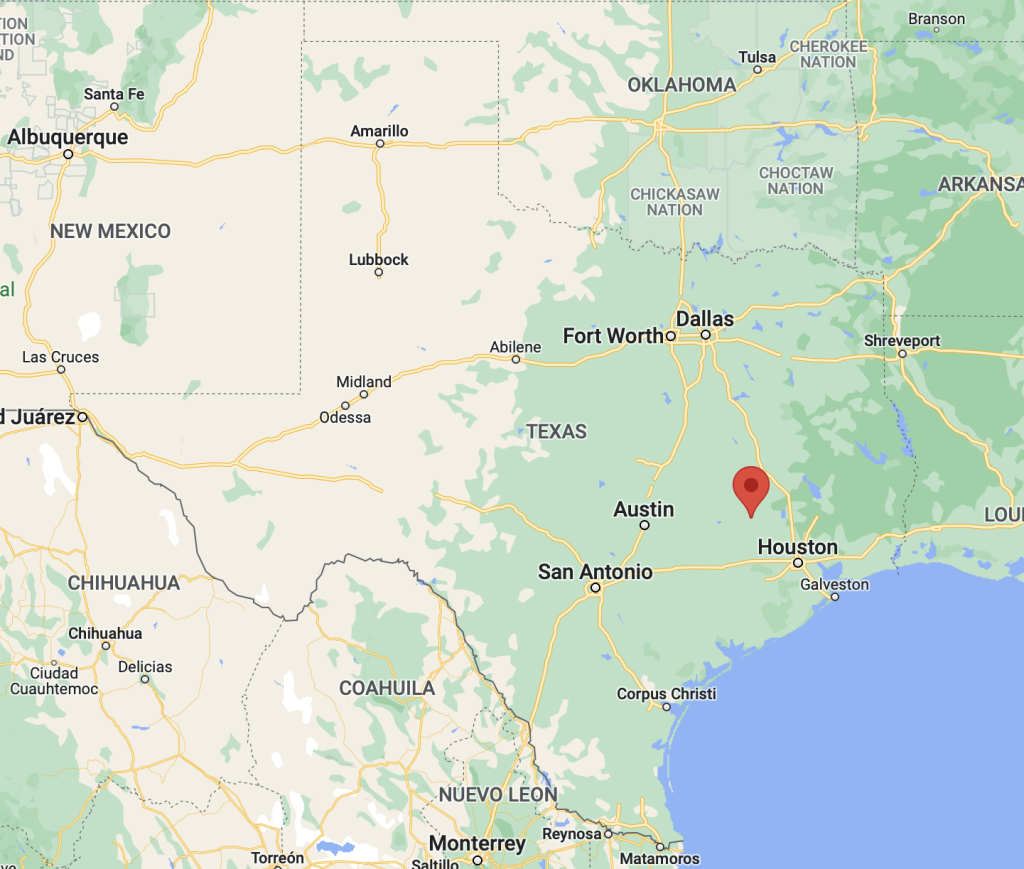

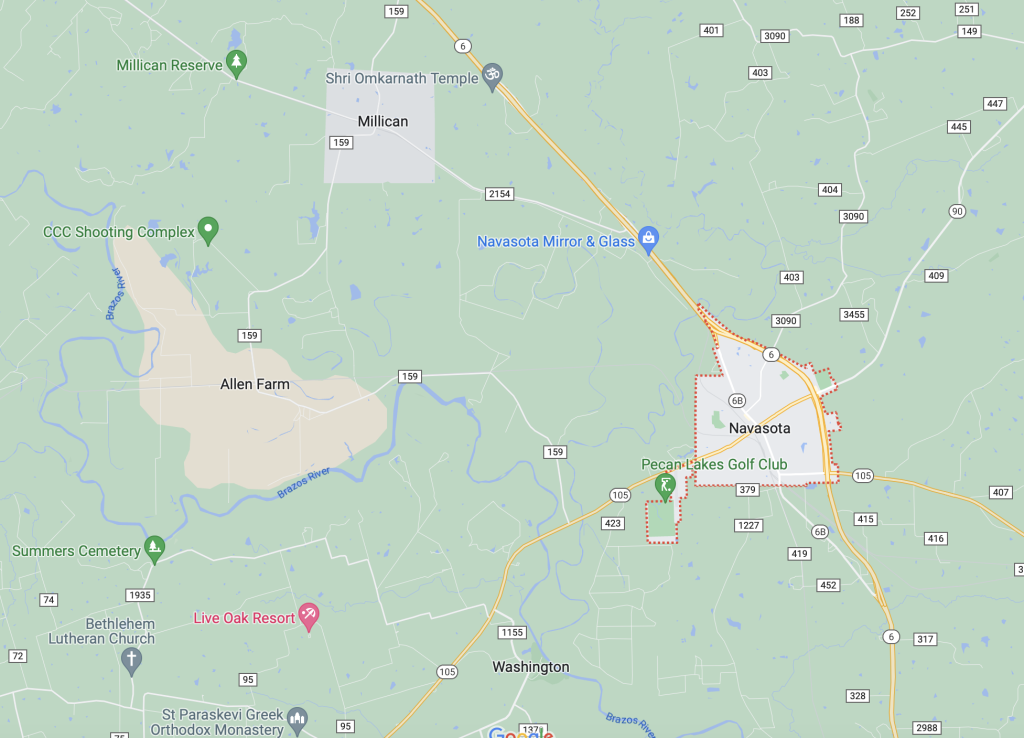

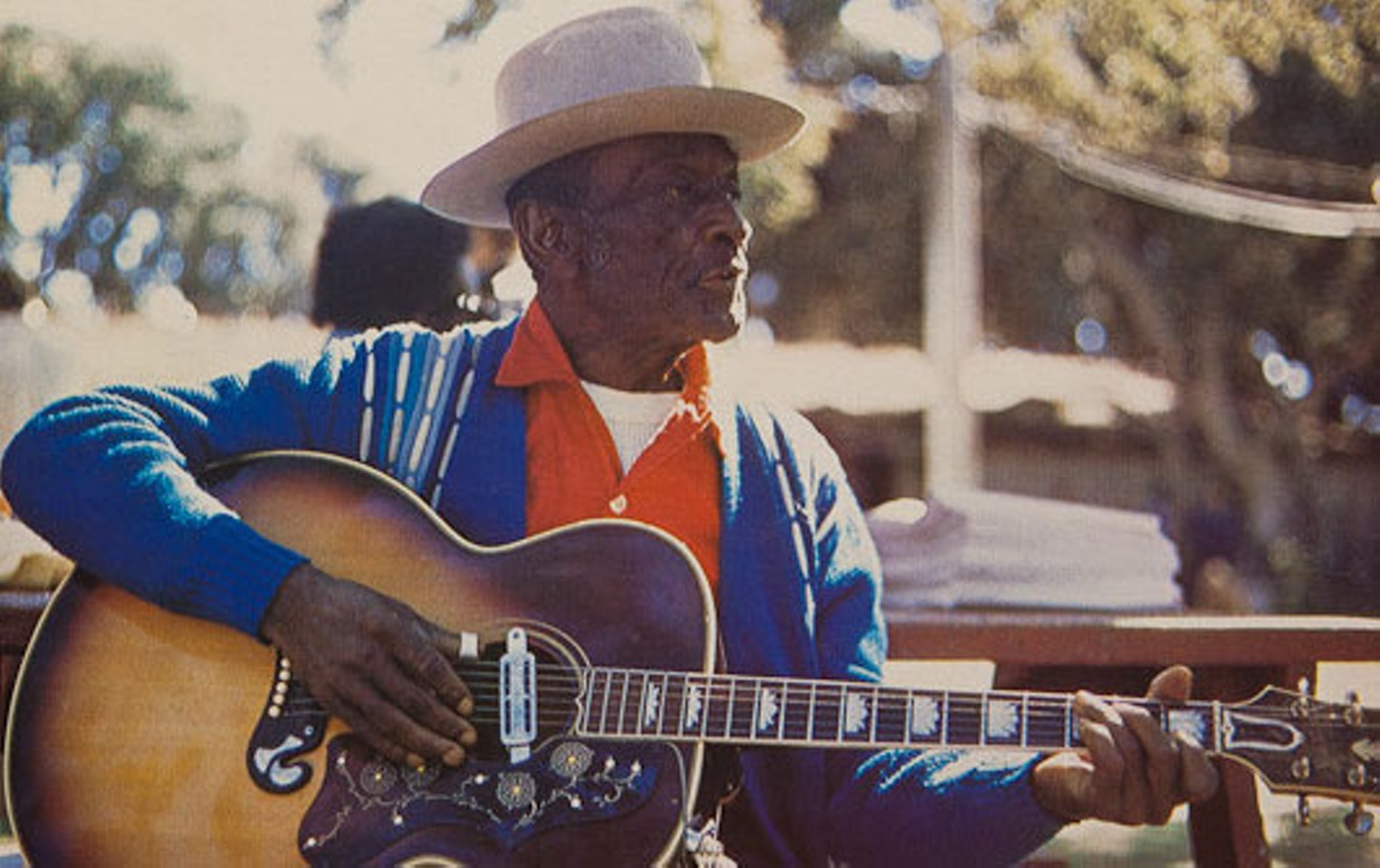

Mance Lipscomb was born in April of 1895 in Navasota, Texas, where he would live his entire life. He was originally named Beau D. Glen Lipscomb, but adopted the name “Mance” as a nickname given to him: short for “emancipation”. Just 30 years prior to his birth on June 19th of 1865, His father was a former slave and his mother was half Black and half Native American. Growing up, Mance’s mother would sing out in the fields as they worked together. A self-taught musician, his father Charlie Lipscomb played the fiddle at local events and dances, and as soon as Mance was old enough he joined his father. The two would play together, with Mance on the guitar at as young as thirteen.

Reconstruction in Texas

Just as Lipscomb was introduced to music early on in his life, he was also a subjected to racism and violence from a very young age. Shootings and street violence were commonplace in Navasota during Lipscomb’s childhood. Born during the reconstruction period- after Texas had rejoined the United States after the end of the Civil War in 1865, Lipscomb witnessed much of the turmoil that came with this period.

The people of Navasota experienced not only the terror of slavery but the horrors of reconstruction. Slave-owning Anglo landowners, outraged at the outcome of the Civil War, sought to circumvent the outlawing of slavery in the United States. They devised systems of inequality to maintain their power, one of which being the sharecropping system that Lipscomb was a part of. Segregation and “Jim Crow” laws were instated in the greater South to keep Black communities at a social and societal disadvantage. Practices such as sharecropping and tenant farming kept Black people in a state of perpetual servitude and poverty, making them economically disadvantaged as well. Many formerly slave-owning Texans defied the outlawing of slavery, maintaining a “come and take it” attitude towards the people they saw as their property. As a result, pro-slavery Anglo Texans organized themselves in order to intimidate Black people into subservience. The most prominent of these groups was the Ku Klux Klan, which rose to power in the years following Emancipation. Black people were being lynched in Navasota by white supremacists, and white plantation owners were abusing and killing black people with almost no repercussions.

Acoustic Blues

Lipscomb’s music can be defined as “acoustic blues”, a subgenre of blues music that originated in the United States in the early 1900s. Acoustic blues has a more raw and stripped-down instrumental sound consisting of just vocals and acoustic guitar, yet it upholds the themes and musical structures present in traditional blues music. Just like traditional blues, acoustic blues holds a deeply political history, and has been used throughout time as a means of African-American storytelling, as well as a vessel for both emotional and political expression.

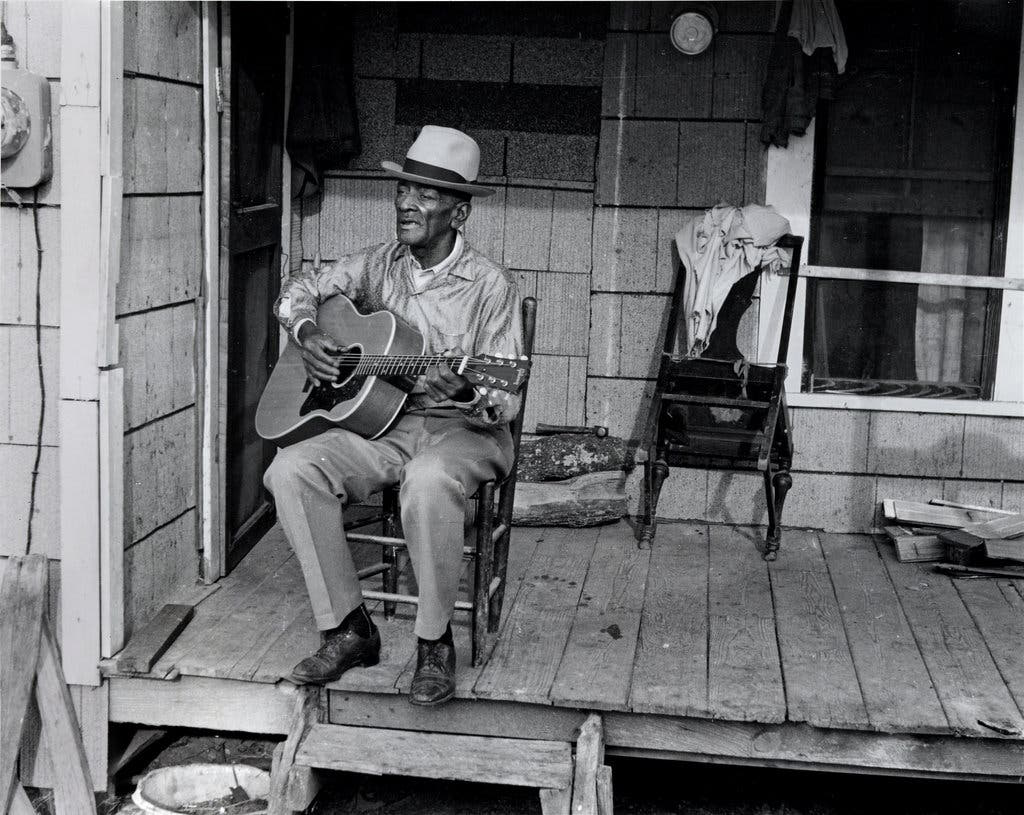

Lipscomb created many songs during his lifetime that fit into this genre, although he is also known to have a more eclectic approach to the blues than other artists. Lipscomb continued to play his guitar long after the days of performing alongside his father, and with just his guitar and his voice he would entertain weekend crowds at events and parties held by both the white and the black communities. “Tom Moore’s Farm” became a crowd favorite, despite Lipscomb’s hesitance to perform the song due to its subject matter being viewed as highly controversial and outright dangerous to discuss at the time.

“Tom Moore’s Farm”

The story behind “Tom Moore’s Farm” is one of hardship, describing the tumultuous living conditions of a Black sharecropper and his hateful feelings towards those conditions (or more specifically, to the one enforcing them onto him). Ultimately, it is a song of resistance to the racist institutions created and upheld by land-owning, predominantly white men who supported slavery. Originally made in the 1930s, the song tells the story of a day on the infamous Moore plantation from the perspective of a Black man who lives and works there. Although Lipscomb is credited with the writing and performing of the song, the story and lyrics come from the first-hand experiences of fellow sharecropper Yank Thornton. Thornton worked on the Moore farm and came to Lipscomb, who was established as a local musician, with his lyrics depicting the harsh reality of Tom Moore’s farm. Lipscomb, although he himself didn’t work on Moore’s farm, helped to illuminate Thornton’s words through his singing and guitar playing.

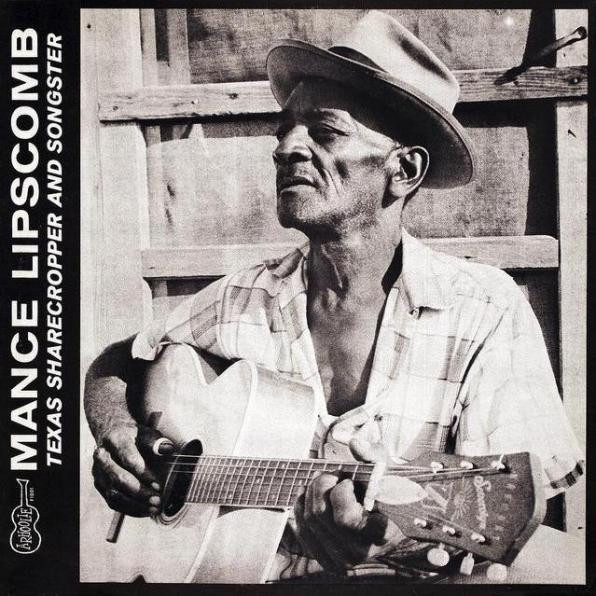

Despite the song being developed in the 1930s, it wasn’t recorded by Lipscomb until decades later. In late June of 1960, Chris Strachwitz traveled to Texas to record blues legend Lightnin’ Hopkins, who had coincidentally recorded and released a version of “Tom Moore’s Farm” in 1949. This version hit the charts as a “race record”, a category which carries its own history as a way for the music industry to separate Black artists from rising to mainstream status. However, Strachwitz’s plans with Hopkins fell through and Strachwitz, in search of another blues musician to record, came across Mance Lipscomb. After traveling to Navasota and recording Lipscomb in his house, Strachwitz decided to start Arhoolie Records. An LP of Lipscomb’s music, entitled Mance Lipscomb – Texas Sharecropper and Songster was the first record to be released by the label.

In 1960 when Lipscomb was first recorded playing “Tom Moore’s Farm”, he did so under the condition that he would be kept anonymous on the record. He feared a violent response from Moore, and refused to play the song anywhere in Eastern Texas for decades. In the outro of the recorded version, Lipscomb expressed this fear stating, “Now if he (Moore) knew I put out a song like that, I couldn’t live here no more. ‘God damn you made a song about me and they made a record of it, I’m gonna kill you’… I wouldn’t live six months if he know that.”

Instrumentals, Lyrics, and Variations

The instrumentals feature the aforementioned acoustic guitar and vocals, both of which are emotionally riveting in their own ways. Lipscomb uses an expressive fingerpicking style, playing so that the guitar “fills in” or “responds” in between the lines. The lines within the verses themselves follow an AAB structure commonly found in blues music. This structure can be connected to the “call and response” formatting of lyrics, as well as the narrative and storytelling function of blues music. Lipscomb’s voice is expressive in a similar way to the guitar in the sense that both feel very forceful and full of emotion, almost as if they are whining or wailing to one another.

The lyrics reference several topics pertaining to life on the plantation and the racism endured by Black people there (on an individual level, but can allude to systemic oppression). The narrator, a sharecropper on Moore’s farm, clearly expresses his disdain for Tom Moore and the cruel manner in which he and his brothers Harry, Clarence, and Steve operate the farm.

“Ain′t but the one thing, see what I done wrong

Ain’t but the one thing, see what I done wrong

Moved my my family down on Tom Moore′s farm”

In the first verse of the song, the narrator immediately makes it known that he regrets moving onto Tom Moore’s farm and bringing his family with him. This sets the stage for the rest of the song, which details the different ways in which Moore makes life on his farm a living hell (The 1960 recording outright mentions Moore using a whip, and both versions talk about the brutally long, monotonous workdays and sparse meals).

Tom Moore′ll tell you, got a smile or grin

Tom Moore’ll tell you, got a smile or grin

Get away from the cemetery boy, keep you from the pen

This verse points at a larger issue at hand, stating that the only two options for people in the narrator’s position are on the plantation, in “the pen”- short for penitentiary, or six feet underground. The first two lines are likely in reference to the circumstances in which Moore would remind the farmers of his power over them. If he saw the farmers with a “smile or grin”, he would assume they are joking around about him and remind them of where he would send them if they continued: to the cemetery or to the pen.

“Tom Moore got way, most in a man I like

Tom Moore got way, most in a man I like

Your woman quit you, have her brought right back”

This is the last verse of the song which touches upon not only racism and slavery but on its ties to sexism, masculinity, and patriarchal ideals. A very loaded verse, the narrator begins by telling us that Tom Moore has characteristics that he likes to see in a man. He continues with saying that this quality is the ability to have his wife brought back when she leaves him. The last line is likely metaphorical and is referencing to the mistreatment of slaves and sharecroppers alike If either were to try to run away from their plantation, the plantation owner would have slave catchers sent after them to bring them back. This verse points out the corruption of systemic racism through the lens of sexism, with the narrator sarcastically stating that he not only admires this quality in Moore, but likes to see it in a man. By transcending the conversation of race and comparing the practices of slavery to domestic violence, the narrator is able to create a broader understanding of systemic racism by putting it in the context of another form of abuse. Not all white Americans understood how slavery and the practices that derived from it were abusive, but they could understand how it would be wrong to do the same to a partner that left them. Perhaps the narrator is also pointing towards the intersection between racism and sexism in white patriarchal ideals, stating that Moore’s treatment of Black people is a reflection of his treatment of the women in his life.

Lyrics for "Tom Moore's Farm" by Mance Lipscomb- live performance version Ain′t but the one thing, see what I done wrong Ain't but the one thing, see what I done wrong Moved my my family down on Tom Moore′s farm Go to work in the morning, don't stop till one o'clock Go to work in the morning, don′t stop till one o′clock Hold back on the time Mister Tom, you can't hold back dark Tom Moore′ll tell you, got a smile or grin Tom Moore'll tell you, got a smile or grin Get away from the cemetery boy, keep you from the pen Want some money, man for Christmas eve Want some money boys, man for Christmas eve Ask Tom or Harry, Clarence or Mister Steve Soon in the morning, baby now so soon Soon in the morning, baby now so soon Dog me that Mister Tom, let someone have my room Soon in the morning then you, get your ham and egg Soon in the morning you will, get your ham and egg Ring that big bell you better, check that mule′s head Done the time come you gon', get your bread and beans Done the time come you gon′, serve your gravy and beans Ring that bell you better, check that boiling tin Tom Moore got way, most in a man I like Tom Moore got way, most in a man I like Your woman quit you, have her brought right back

Black Resilience and the Legacy of The Blues

The Moore farm was infamous for its continuation of racist practices from the times of legal slavery. It was in many ways a penitentiary itself, perpetuating generations of indentured servitude to Tom Moore and his family. The presence of the Tom Moore farm and the White Man’s Union Association (a white supremacist group in the Navasota area) during reconstruction and post-reconstruction upheld racist ideologies held by many other places in the Deep South, ideologies that justified the horrific mistreatment of African Americans and the mindset that the only three places they were meant to be were the plantation, jail, or the graveyard. Despite all of these hardships, African Americans found ways of sharing their stories with each other and eventually, with the world through the performance of blues music.

The origins of the blues is inseparable from the history of slavery, just as the history of slavery is inseparable from the history of Texas (and subsequently, the history of America too). However, there are stories of perseverance, resistance, and resilience amidst this historical oppression: stories like those of Yank Thornton and Mance Lipscomb.

At the beginning of the live version, Lipscomb makes a joke to his audience. When an audience member asks him to sing the song about Tom Moore, Lipscomb says yes and laughs, exclaiming “oh well he can’t hear me”. With so few words, Lipscomb is telling his audience that he is in a place where he feels comfortable enough to not only play the song uncensored, but to joke about the idea of Moore being able to hear him. Lipscomb lived in fear of Tom Moore and people like him for the greater part of his life, but for a brief moment through his music and the support of his audience, Lipscomb is able to escape that.

“Go to work in the morning, don’t stop till one o’clock

Go to work in the morning, don′t stop till one o′clock

Hold back on the time Mister Tom, you can’t hold back dark”

Although Moore and racist landowners like him had power to make the work days as long and grueling as they wanted, they couldn’t control the passage of time. The sun will eventually set, it will be dark out, and the day will be over. The weekend will come, and Black communities will be able to gather- to sing and dance together, to laugh and to share their hardships with one another. One way or another, they will find away to share their stories and bring to light the oppression they have faced, and ultimately, overcame.

Sources:

“Blues.” TSHA, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/blues.

“Influence on the Blues.” UTSA Institute of Texan Cultures Sharecropper Cabin, 11 Nov. 2021, https://texancultures.utsa.edu/cabin/blues/.

“Lipscomb, Mance (1895–1976).” TSHA, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/lipscomb-mance.

McCormick, Mack. “A Treasury of Field Recordings Volume Two- Notes.” Arhoolie Records, 1960.

Obrecht, Jas. “Let It Roll!- The Essential Blues Sessions.” Living Blues, Jan. 2023, https://digital.livingblues.com/publication/?i=778106&article_id=4460571&view=articleBrowser.

Prather, Coy. “Story behind the Song: ‘Tom Moore’s Farm.’” Texas Music Magazine, 6 Sept. 2021, https://txmusic.com/story-behind-the-song-tom-moores-farm/.