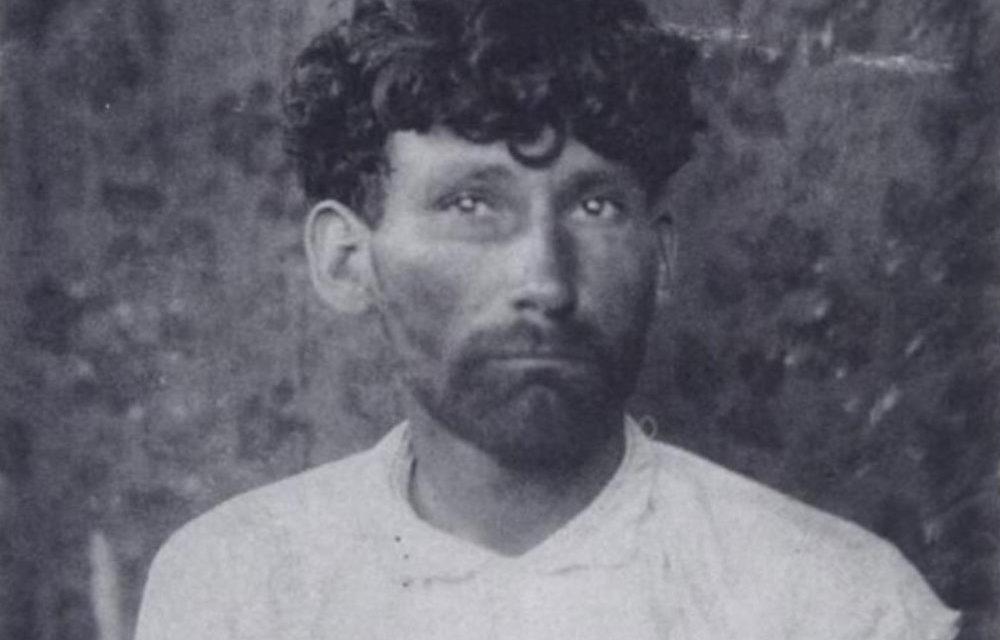

Who is Gregorio Cortéz?

Gregorio Cortéz was born on June 22, 1875, near Matamoros, Tamaulipas. After his family moved to Texas in 1887, he began working as a vaquero (cowboy). In 1901, he fatally shot Sheriff Morris in self-defense when Morris incorrectly accused Cortéz and his brother Romaldo of stealing horses. Cortéz then fled town after making sure his family was safe. He managed to elude capture for two weeks in one of the most famous manhunts in history. Over 600 men attempted to capture him. After eventually learning that his wife and children had been jailed, Cortéz surrendered himself. Despite being convicted of Morris’s murder and beginning a life sentence, he was pardoned in 1913. After being pardoned, he went to Nuevo Laredo and fought with Victoriano Huerta in the Mexican Revolution. Cortéz quickly become a border folk hero. Overtime, he also came to represent the inequality of justice between the Hispanic settlers and the Anglo settlers. There were already strict tensions between the Hispanic settlers and the Anglo settlers long before Gregorio’s flight from the authorities. However, his story truly brought to light the differences in how Hispanics were treated in comparison to Anglos. Disregarding the fact that there was a language barrier that prevented true justice from availing, Gregorio was treated immensely differently from how Morris would have been, despite the fact that they committed the same “crime.” Gregorio was eventually sentenced to a life sentence for killing Sheriff Morris, as mentioned above, but Morris would have faced practically no consequences for killing Romaldo, Gregorio’s brother.

About the Song

I was unable to locate any information on the artists, Pedro Rocha and Lupe Martínez. However, I was able to find some information on the song itself. This song was released in 1929, which was in between the end of World War I and the beginning of World War II. While this may have influenced the production of this song, in Mexico, another event is much more likely to have influenced Rocha and Martínez: the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920). The Mexican Revolution is often considered to be the first major conflict of the 20th century. The main motive for the revolution was challenging the regime of dictator Porfirio Díaz, who had been in power for over 30 years, which violated the Mexican Constitution of 1857. After approximately 6 months of conflict, Díaz resigned and left Mexico. Francisco I. Madero, who called for the uprising against the former dictator, eventually became president after the 1911 elections. Victoriano Huerta, whom Gregorio Cortéz fought with, assassinated Madero in 1913. Interestingly, Cortéz, who was known for his legacy of resistance, fought on the side of the counterrevolutionaries rather than on the side that resisted the dictatorship. In addition to the historical elements of the song, there are several stylistic choices that are tejano in nature. For example, this song uses close harmony singing, as well as a “1, 2, 3 ” waltz feel. Both of these are commonly used in tejano music.

Lyrics, Translation, and Discussion

En el condado del Carmen (In the county of the Carmen)

miren lo que ha sucedido. (look what has happened.)

Murió el sherife mayor (The sheriff died leaving)

quedando Román herido. (Román wounded.)

Otro día por la mañana (The following morning)

cuando la gente llegó, (when the people arrived,)

unos a los otros dicen (some said to the others)

no saben quien lo mató.(they don’t know who killed him.)

Se anduvieron informando (They were investigating)

como tres horas después, (and about three hours later,)

supieron que el malhechor (they found that the wrongdoer)

era Gregorio Cortéz. (was Gregorio Cortéz.)

Insortaron a Cortéz (Cortéz was wanted)

por toditito el estado. (throughout the state.)

Vivo o muerto que se aprehenda (Alive or dead may he be apprehended)

porque a varios ha matado. (for he has killed several.)

Decía Gregorio Cortéz (Said Gregorio Cortéz)

con su pistola en la mano, (with his pistol in his hand,)

-No siento haberlo matado (“I’m not sorry for having killed him,)

al que siento es a mi hermano.- (it’s for my brother that I feel sorry.”)

Decía Gregorio Cortéz (Said Gregorio Cortéz)

con su alma muy encendida, (with his soul aflame,)

-No siento haberlo matado (“I’m not sorry for having killed him,”)

la defensa es permitada.- (self defense is permitted.”)

Venían los americanos. (The Americans came.)

Que por el viento volaban (They flew like the wind)

porque se iban a ganar (because they were going to win)

tres mil pesos que les daban. (the three thousand pesos reward.)

Siguió con rumba a Gonzáles. (They continued toward Gonzáles.)

Varios sherifes lo vieron. (Several sheriffs saw him.)

No lo quisieron seguir (They did not want to continue)

porque le tuvieron miedo. (because they were afraid of him.)

Venían los perros jaunes, (Came the hound dogs,)

venían sobre la huella. (they came on his trail.)

Pero alcanzar a Cortéz (But to reach Cortéz)

Era alcanzar a una estrella (was to reach a star.)

Decía Gregorio Cortéz (Gregorio Cortéz said,)

-Pa´ qué se valen de planes (“What’s the use of plans)

si no pueden agarrarme (if you can’t catch me)

ni con esos perros jaunes.- (even with those hound dogs.”)

Decían los americanos (The Americans said)

-Si lo vemos que le haremos (“If we see him what shall we do to him;)

Si le entramos por derecho (If we face him head on)

muy poquitos volveremos.- (very few will return.)

En el redondel del rancho (In the ranch corral)

lo alcanzaron a rodear, (they managed to surround him.)

Poquitos más de trescientos (A little more than 300 men)

y allí les brincó el corral. (and there he gave them the slip.)

Allá por el Encinal (There around Encinal)

a según por lo que dicen (from all that they say.)

Se agarraron a balazos (They had a shoot-out)

y les mató otro sherife. (and he killed another sheriff.)

Decía Gregorio Cortéz (Gregorio Cortéz said)

con su pistola en la mano, (with his pistol in his hand,)

-No corran rinches cobardes (“Don’t run, you cowardly Rangers)

con un solo mexicano.- (from one lone Mexican.”)

Giró con rumbo a Laredo (He turned toward Laredo)

sin ninguna timidez, (without a single fear,)

-¡Síganme rinches cobardes, (“Follow me, you cowardly Rangers,)

yo soy Gregorio Cortéz!- (I am Gregorio Cortéz.”)

Gregorio le dice a Juan (Gregorio says to Juan)

en el rancho del Ciprés, (at the ranch of the Cypress,)

-Platícame qué hay de nuevo, (“Tell me what’s new,)

yo soy Gregorio Cortéz.- (I am Gregorio Cortéz.”)

Gregorio le dice a Juan, (Gregorio says to Juan,)

-Muy pronto lo vas a ver, (“Very soon you will see,)

anda hablale a los sherifes (go and talk to the sheriffs)

que me vengan a aprehender.- (that they should come and arrest.”)

Cuando llegan los sherifes (When the sheriffs arrive)

Gregorio se presentó, (Gregorio presented himself,)

-Por la buena si me llevan (“You’ll take me if I wish it,)

porque de otro modo no.- (because there is no other way.”)

Ya agarraron a Cortéz, (Now they caught Cortéz,)

ya terminó la cuestión. (now the case is closed.)

La pobre de su familia (His poor family)

la lleva en el corazón. (he carries in his heart.)

Ya con esto me despido (Now with this I take my leave)

con la sombra de un Ciprés. (in the shade of a cypress.)

Aquí se acaba cantando (Here we finish singing)

la tragedia de Cortéz. (the tragedy of Cortéz.)

This song tells the tale of Gregorio Cortéz as he runs from the authorities after killing Sheriff Morris. While explaining the travel route of Cortéz while he fled the authorities, the song references five cities/counties that are in Texas. The song itself is a corrido, a traditional Mexican song style that is used for storytelling, and it is a version of Mexican folk music. Corridos often tell of battles, political resistance, the lives of notorious people, and the epic journey of life. This style of song also often includes many stringed instruments, such as the guitar that is clearly heard throughout the ballad.

Sources

“Corridos: Stories Told Through Song.” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/corridos-stories-told-through-song.htm.

“Gregorio Cortez.” Fresno State University, https://www.fresnostate.edu/folklore/ballads/CAFS2526.html.

“Gregorio Cortez.” University of Texas, 7 May 2001, https://www.laits.utexas.edu/jaime/jnicolopulos/cwp3/icg/cortez/index.html.

Orozco, Cynthia E. “Cortez Lira, Gregorio (1875-1916).” Texas State Historical Association, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/cortez-lira-gregorio.

Rocha, Pedro and Martínez, Lupe. “Gregorio Cortéz.” Corridos & Tragedias de la Frontera, Arhoole Records, 1929, https://folkways-media.si.edu/docs/folkways/artwork/ARH07019.pdf.

Rodriguez, Leonard. “Gregorio Lira Cortez.” La Prensa Texas, 20 November 2020, https://laprensatexas.com/gregorio-lira-cortez/.

“The Mexican Revolution: November 20th, 1910.” National Endowment for the Humanities, 19 March 2012, https://edsitement.neh.gov/closer-readings/mexican-revolution-november-20th-1910.