Please consider my post an example of what I want each of you to do for assignment #3. It offers a structure that will allow each of you to think about phenomena, epistemologies, assumptions, and methods in the disciplines you’re exploring for your project. Please come to class ready to discuss a passage from this post or from one of the sources I cite in this post. It’s okay to select a passage because it confuses you! Most of what I read in the articles I cite below still confuses me!!

Phenomena

“Phenomena are the subjects, objects, and behaviors that a discipline considers to fall within its research domain” (Repko 102).

I have discovered the following things about the disciplines I’m engaging for my project from Table 5.4, “Disciplines and the Phenomena They Study” (Repko 103-5):

Phenomena in Literature

“Development and examination (i.e., both traditional literary analysis and theory as well as more contemporary culture-based contextualism and critique) of creative works of the written word” (104).

This is the primary domain of my project and my primary object in this is project is to help students get more engaged in the experience of “creative works of the written word” (something they are increasingly skipping)

Phenomena in Psychology

“The nature of human behavior as well as the internal (psychosocial) and external (environmental) factors that affect this behavior” (Repko 104).

When I think of the study of human emotion, I think of psychology. There are lots of ways to study human emotion, but the one I’m most interested in is cognitive neuroscience, which is an interdisciplinary field that draws on information from biology.

The particular phenomenon I’m interested in (human emotion) isn’t listed in Repko’s table, but if you think of emotion as originating with the firing of particular neurons (as I do), then we’re talking about a biological process.

Phenomena in Biology

“Biological taxonomies of species; the nature, interrelationships, and evolution of living organisms; health; nutrition; disease; fertility” (Repko 103).

Phenomena in Mathematics

“The logic of numbers, statistics, mathematical modeling, computer simulations, theoretical counterpoint to sensitivity analysis” (Repko 103).

The most relevant to my project is mathematical modeling, which I am using to represent, as a network graph, actual reading experiences. Statistics is also relevant to what I am studying if I move into gathering quantitative data from readers and want to study my results in a rigorous way. I think it’s noteworthy that statistics emerges from the discipline of mathematics, though it is a common part of the methodology in psychology and biology.

Epistemology

“Epistemology is the study of nature and basis of knowledge that answers questions including the following: What is the nature of knowledge? How can I know what I know? What is truth? How much can we know?” (Repko 103).

Epistemologies of Literature

I’m disappointed with the representation of literature in table 5.8, but Repko does say that “the humanities, even more so than the social sciences, embrace multiple epistemologies” and “the humanities prize diversity of perspective, values, and ways of knowing” (Repko 109).

Epistemologies of Psychology

“The epistemology of psychology is that psychological constructs and their interrelationships can be inferred through discussion and observation and applied to treatment (clinical) or a series of experiments with slight variations (experimental). A critical ingredient of a good experiment is experimental control that seeks to eliminate extraneous factors that might affect the outcome of the study” (Repko 107).

So, when I think about how I want people to report their emotional responses to literature they’ve read, I wonder how I can do this as accurately as possible. I gravitate toward a survey (or even extracting this information from things students have written), but I’m also very curious about how researchers have employed brain scans to see how synapses are activated when experiencing a work of a literature. This is specifically in the realm of cognitive neuroscience.

Epistemologies of Biology

“Empiricism, the ruling ideology of science, assures us that observation and experimentation make scientific explanations credible and the predictive power of its theories ever increasing (106).

“Biology stresses the value of classification and experimental control. The latter is the means of identifying true causes, and which therefore privileges experimental methods (because they are replicable) over all other methods of obtaining information” (106).

I used Google translate to understand the description of this image from the description in the flickr album and the translations says, “A team of researchers from Linz invited people to take part in a study in the temporary Neuro-Lab of the Ars Electronica Center that aims to make internal evaluation processes visible in the brain.”

Epistemologies of Mathematics

“Mathematical truths are numerical abstraction that are discoverable through logic and reasoning. These truths exist independently of our ability or lack of ability to find them, and they do not change” (Repko 106). I think this applies to the realm of graph theory because graphs are essentially another way of creating a representation of data. I have no illusion that I will somehow map the human experience of literature perfectly, though I think this is what most recommender systems are doing when they make a good guess about what you’ll like based on your previous listening/viewing habits (and the habits of those who like the things you like). I think statistics often lead us astray, but I like a nice visualization.

Assumptions

Assumptions in the Natural Sciences

- “The natural sciences study the natural world whose behavior is fixed or governed by instinct or evolution”

- Nature is orderly

- We can know nature

- All natural phenomena have natural causes

- Knowledge is based on experience

- Knowledge is superior to believe unsupported by empirical evidence

- Scientists can transcend their cultural experience and make definitive measurements of phenomena

- There are no supernatural or other a priori properties of nature that cannot potentially be measured” (110)

I don’t know if my colleagues in the natural sciences believe that they can make measurements of phenomena that aren’t impacted by their own cultural experiences. Now I want to ask them.

Assumptions in the Social Sciences

“The social sciences assume that there is some order to society…The social sciences study the world of sentient, willful humans who imagine future and alternative states to the world as it currently is and change their patterns of behavior in light of anticipated or desired futures as well as present realities” (110).

Assumptions in the Humanities

The humanities “share many of the assumptions of the social sciences” (110). I disagree with the other characterizations of the assumptions of the humanities in the book, which I think just points to the fact that it’s hard to generalize assumptions for an entire discipline. We disagree way too much in the humanities for a book to be able to summarize the assumptions all humanists make. The way the assumptions of the humanities are characterized in this book also makes me think that I am a humanist who is pretty influenced by the natural and social sciences (not many other English professors want to study literary phenomena by surveying students or scanning their brains).

Identifying Methods in Actual Articles

For methods, I am finding a scholarly article related to my project in three specific fields. The journals I’m looking at address very specific fields within the larger disciplines I explored above, and these fields are occasionally already interdisciplinary in nature. I’m reading these articles and pulling specific passages that help me understand the relationship between the methods of the discipline and the phenomena, epistemologies, and assumptions about that field.

Mathematics

Pupyrev, Sergey, et al. “Edge Routing with Ordered Bundles.” Computational Geometry, vol. 52, Feb. 2016, pp. 18–33. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comgeo.2015.10.005.

To find this article, I did a quick search on the library tab in myCharger for the term “edge bundling,” a term I encountered but didn’t understand in the tool I’ve been using to make network graphs. Here are some quotes I found from the article:

“Graph drawing is often used in information visualization for exploring and analyzing network data. The core components of most graph drawing algorithms are the computation of positions of the nodes and edge routing. In this paper we concentrate on the latter problem.”

“The problem of drawing edges as curves has been considered in several visualization papers. Such edges, with their smoother and organic shape, have an aesthetic appeal to humans, who are known to prefer round shapes [3]“

I’m not going to claim to understand the formulas in this article (an example is in the image above), but I do get the basic gist of what’s happening. The authors are creating algorithms (essentially, instructions for the computer) that will arrange nodes (the circles in the graph) and draw edges (the lines connecting the nodes) so the data is easier to understand visually. Until I looked at this article, I didn’t realize how much work goes into making the free tools people use to create network graphs, but it’s a ton of work! And it’s no wonder my network graphs aren’t immediately beautiful. I don’t know how to make choices between the many algorithms mathematicians have created to optimize graphs. It’s like if I wanted to make a delicious meal but didn’t yet know that a steak tastes more delicious when it’s left a little pink in the center, salt makes everything more delicious, and soft mashed potatoes are a nice texture to accompany steak (as opposed to roasted and crispy potatoes). I don’t have to invent these cooking methods (the algorithms), but I should learn how others use them and in what combination.

So, to sum up my thoughts about this article…

Phenomena

The logic of mathematical modeling is the phenomena being highlighted in this article. It is not a study of how these things behave so much as a report on one method for handling data.

Epistemology

I don’t actually see a strong claim that the visualization accomplishes some sort of truth about the data used to create it. One might expect something like this, but it seemed to me that the authors had more practical concerns. It does seem that they believe that the proper arrangement of algorithms can eventually result in a satisfying visualization of complex data. It’s just a matter of getting the computing instructions sorted out.

Assumptions

It’s hard to find assumptions in this work, which might be because the article is more about method than results of a study.

Methods

The methods are the primary focus and the authors are sharing a series of algorithms that can create a more pleasing visualization.

Cognitive Neuroscience

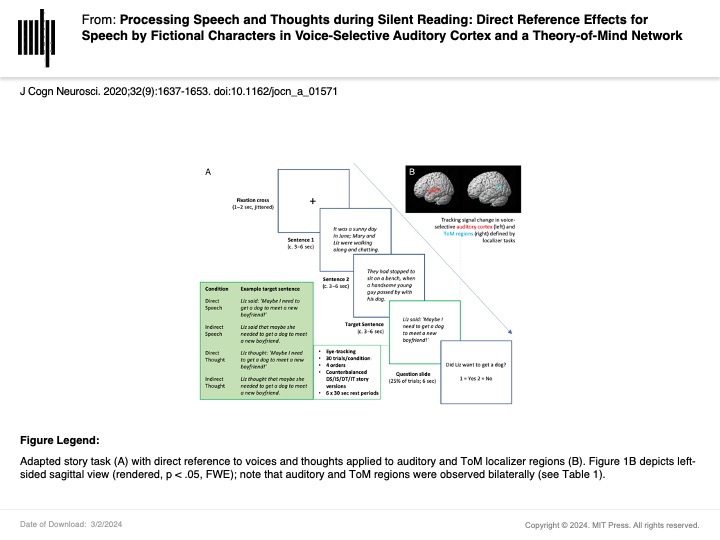

Alderson-Day, Ben, et al. “Processing Speech and Thoughts during Silent Reading: Direct Reference Effects for Speech by Fictional Characters in Voice-Selective Auditory Cortex and a Theory-of-Mind Network.” Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, vol. 32, no. 9, Sept. 2020, pp. 1637–53. Silverchair, https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_01571.

To find this article, I searched for journals in cognitive neuroscience and decided that Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience would be a good one to search within. I was able to just enter my search terms into the search bar at the top of the journal’s public website. I first searched for “literature,” but got lots of irrelevant results because everyone includes a “literature review,” which means something different than I meant. I then searched for “narrative” and got interesting articles, but searched again for “free indirect” because I’ve just been studying this narrative technique with my students. I chose this article because I wanted to learn more about how fMRI is used to study silent reading, and I found the introduction very intriguing:

Stories can conjure complex imaginative worlds that offer immersion and transportation for the reader (Green, 2004; Green, Brock, & Kaufman, 2004; Ryan, 1999; Gerrig, 1993). Fictional characters in particular are sometimes experienced with a vividness and complexity, which can linger beyond the page (Alderson-Day, Bernini, & Fernyhough, 2017; Maslej, Oatley, & Mar, 2017). Understanding how these experiences are created by the mind—often with apparent automaticity and spontaneity—is a challenge for a wide range of disciplines beyond psychology, including literary theory, narratology, philosophy of mind, and cognitive neuroscience (Herman, 2013). Far from passively “receiving” information from the writer, readers actively and creatively engage with fictional texts in a way that draws on multiple psychological resources (Polvinen, 2016; Caracciolo, 2014; Kukkonen, 2014; Oatley, 2011; Bortolussi & Dixon, 2003).

-Alderson-Day et al. n.p.

First of all, it’s fascinating to read an article in this journal that explains the phenomena of literature so accurately. I was also excited to find that Marie-Laure Ryan and David Herman (two narrative theorists I’ve read) are cited in the introduction.

One approach to understanding the qualitative richness of the reading experience has been to study inner speech (sometimes also referred to as inner monologue or articulatory imagery; Alderson-Day & Fernyhough, 2015; Perrone-Bertolotti, Rapin, Lachaux, Baciu, & Lœvenbruck, 2014). Intuitively, reading is often associated with the sounding out of an “inner voice,” and the self-reports of readers involve various kinds of auditory imagery when engaged in a story (Vilhauer, 2016). Although the reliability of readers’ introspective reports has been questioned (Caracciolo & Hurlburt, 2016), empirical evidence of inner speech involvement during silent reading is well documented (Filik & Barber, 2011; Alexander & Nygaard, 2008). Moreover, silent reading appears to elicit activity in perisylvian regions and auditory association cortex (Magrassi, Aromataris, Cabrini, Annovazzi-Lodi, & Moro, 2015; Perrone-Bertolotti et al., 2012), particularly when characters’ voices and speech are being described (Brück, Kreifelts, Gößling-Arnold, Wertheimer, & Wildgruber, 2014; Yao, Belin, & Scheepers, 2011). Such findings have been taken as evidence of the reading experience—and its evocation of inner speech—being almost akin to hearing external voices (Petkov & Belin, 2013).

-Alderson-Day et al n.p.

I find this paragraph fascinating because it shows that the “self-reports of readers” have been used as a data source in published research, but the reliability of this information “has been questioned.” There is another way, though! Empiricial evidence that comes from fMRI.

The “data acquisition” section is fascinating to me:

fMRI data were acquired at Durham University Neuroimaging Centre using a 3-T Magnetom Trio MRI system (Siemens Medical Systems) with standard gradients and a 32-channel head coil. T2*-weighted axial EPI scans were acquired with the following parameters: field of view = 212 mm, flip angle = 90°, repetition time = 2000 msec, echo time = 30 msec, number of slices = 32, slice thickness = 3.0 mm, interslice gap = 0.3 mm, and matrix size = 64 × 64. Story task data were collected across 2 × 20-min runs consisting of 600 volumes each; auditory and ToM tasks took roughly 10 min each and consisted of 300 and 281 volumes, respectively. The first three volumes of each EPI run were discarded to allow for equilibrium of the T2 response. For each participant, an anatomical scan was acquired using a high-resolution T1-weighted 3-D sequence (number of slices = 192, slice thickness = 1 mm, matrix size = 512 × 512, field of view = 256 mm, echo time = 2.52 msec, repetition time = 2250 msec, flip angle = 9°). Eye-tracking data were collected using a LiveTrack system (Cambridge Research Systems) with MATLAB 2016b (The Mathworks, Inc.).

-Alderson-Day et al n.p.

They’re giving every detail about the machines used to collect data (an fMRI machine and an eye tracking system) and how those machines were set up (the parameters). I asked my husband to look at this to see how it compares to the way he might describe his test setups (he’s an engineer in a test lab at a manufacturing company). He pointed out that they would never share their setups because they are proprietary (trade secrets, essentially). This is an important thing to note about academic science (like an empirical study in the field of neuroscience) and applied science (like a company testing, in a lab, how well new products perform in various environmental conditions). Academic neuroscience is attempting to understand how the brain works, while applied science is trying to make sure a new product will be effective for consumers.

When I think about my own relationship to this sort of study, I can say that I don’t aspire to run an experiment like this. But I would perhaps like to have my research be cited by scholars doing these studies. Neuroscientists are already citing humanists who have published on narratology, and maybe a goal of mine would be to contribute to how example texts are selected when designing such a complex study. Here’s a figure from the article describing the samples for subjects to read silently:

If you look closely, you’ll see that the example passage given to participants is some version of Liz saying or thinking (directly reported or paraphrased) that she might need a dog to meet a new boyfriend. This brings up, to me, the fact that some participants, based on their experiences in life, will be able to imagine a person saying something like this, while other participants might not be familiar with this logic. The one sentence is pretty loaded with gender expectations and the conventions of interaction between potential romantic partners. I kept reading the article to see how this was addressed and the closest the authors come to acknowledging it is in the results sections

Although it is sometimes assumed that direct speech necessarily prompts adopting a first-person perspective (speaking as the character), it is also understood as focusing the reader on what it would be like to hear the character speak to them (Clark & Gerrig, 1990). Similarly, thoughts could be seen to prime a first-person perspective (thinking “from the inside”), but this will likely depend on the position of the narrator, the reader’s identification with the character, and the wider context of the narrative (Kuiken, Miall, & Sikora, 2004). As such, a key area for further exploration is to systematically examine how perspective shifts potentially interact with direct reference effects and speech/thought distinctions.

-Alderson-Day et al n.p.

So, to sum up my observations about this article…

Phenomena

The way neurons fire when a person is silently reading stories that use different strategies for presenting speech and thought. Or, more simply, what happens in our brain when we read silently?

Epistemology

I think this is the clearest example of a study that engages with the empiricism. Experiment is the best way to gather objective information about phenomena in the human brain.

Assumption

What a person reports about their experience is less valuable than empirical data that can be gathered objectively through fMRI and eye scans

The life experiences being portrayed in the narrative samples (and their relationship to the life experiences of the participants in the survey) do not have a bearing on the results.

Methods

Display four different types of narrative reporting speech and thoughts through a screen to participants, tracking their eye movements and brain activity. Interrupt them at key moments to see how this impacts their brain activity. Analyze the results statistically.

Experimental Narrative Theory

Fletcher, Angus, and John Monterosso. “The Science of Free-Indirect Discourse: An Alternate Cognitive Effect.” Narrative, vol. 24, no. 1, Jan. 2016, pp. 82–103.

This article was cited by Alderson-Day et al, but it was published in the journal Narrative, a place where one might expect literary criticism. But this article actually features an experimental study. And it is actually the reason the other article showed up when I searched for “free indirect discourse” (FID) in Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience (because the findings from this article were mentioned in the results section of the other article). Because the study was designed by a literature professor who was also trained as a neuroscientist (Angus Fletcher) and a psychology professor who now studies addiction and self control (John Monterosso), I was very interested to see how the phenomena, epistemologies, assumptions, and methods differed. And the authors get right to the point of epistemology in the introduction:

The recent surge of interest, both popular and professional, in cognitive research on literature has placed literary scholars in a difficult position. On the one hand, literary studies ahs long been committed to welcoming new methodologies into its fold. But on the other, cognitive science employs an epistemology of “reduction” that seems not only foreign, but hostile, to much of literary studies (Easterlin 20). Where literary studies values the qualitative, subjective, autonomous, indeterminate, and endlessly variable, scientific reduction privileges the quantitative, objective, peer-reviewed, controlled, and single variable (Starr; Gottschall).

-Fletcher and Monterosso 83

The authors go on to describe this problem in greater detail to explain why many literary scholars resist engaging with cognitive studies of literature. Essentially, two different disciplines are studying the same phenomenon (the way literature works on the brain), but disparaging each other’s methods. The authors then introduce how their work is going to address the issue:

In this article, we would like to explore an alternative way for literary scholars to protect the autonomy and open-endedness of literary practice from scientific reduction: designing cognitive experiments of their own. That is, rather than rejecting scientific reduction outright, we will inform it with a literary perspective, on that by no means encompasses the vast diversity of literary studies, but that nevertheless draw (and depends) upon it. To model the potential benefits of this more inclusive method of reduction, we will use it to revise a currently popular cognitive interpretation of literature: the theory that novelistic techniques (and in particular, free-indirect discourse, or FID) can improve empathy or “Theory of Mind.”

-Fletcher and Monterosso 83

There are many brilliant things in this article, including a review of existing literature that summarizes the consensus of psychologists who have been studying Theory of Mind while also pointing out results from those studies that contradict the prevailing understanding. Here’s an example of how they do this:

To test this hypothesis, Oatley and his team recruited ninety-four participants into a cognitive study (Mar et al. 2006), discovering that fiction readers (as defined by a familiarity with authors such as Danielle Steel and Robert Ludlum) were better than non-fiction readers at predicting people’s thoughts from photos of their faces (although conversely, other kinds of readers showed a diminished capacity to predict people’s thoughts from their actions).

-Fletcher and Monterosso 85

Because they are skeptical of the results Oatley reports, I sort of expected Fletcher and Monterosso to devise a different sort of study than the one Oatley used, but that’s not what they did. I think their full explanation of their approach is helpful to include:

Although Oatley’s model may not be wholly satisfactory, it thus still has a good deal to recommend it, steering us away from a zero-sum verdict and into a third possibility: perhaps the model tells only part of the story. Perhaps, that is, it captures one–but only one–of the possible cognitive functions for FID. To see if this were the case, we would need to run a psychology survey that employs Oatley’s protocols to test for another such cognitive function. if the survey yielded a positive result, it would indicate that there are multiple scientifically-legitimate interpretations of FID, suggesting that reduction could be used to support a richer, more open-ended account of what novel-reading can do.

Running this sort of survey is relatively straightforward, but designing it is less so. For a cognitive study to be considered valid, it must reduce literature to a single variable, a procedure that would automatically seem to destroy the very open-endedness that we are trying to preserve. In fact, however, scientific reduction only has a culling effect on literary variety when it is applied insensitively. If we begin by assuming that novel is a gigantic transhistorical entity that has evolved to serve on master biological function, then we will only ever run experiments to look for this function, and so reduction will inevitably serve as a tool for squeezing out individual variation. But if we draw on the expertise of literature scholars and instead attend to the cultural and authorial differences between novels, then we can design scientific experiments that acknowledge the endless possibilities of literary form, allowing us to catalog a diverse and ever-increasing set of novelistic techniques that can be adapted to different qualitative effect.

-Fletcher and Monterosso 86-7

I could quote the entire article in this post because I enjoyed so much of it, but I will stop here–encouraging you to read it directly if you’re interested in seeing how this interdisciplinary approach works. I’ll conclude my post here by summarizing my reflections on what I experiences in the article. I will share the results, because they are extremely nuanced

Far from taking on the attitudes of the protagonist, they perceived a division between themselves and the literary consciousness portrayed through FID […] While FID was linked with an increased emotional response, our participants linked this response to the suffering of the victim. In line with the self-restraint method of FID, our results thus associated tolerance not with the first person, but with the third.

-Fletcher and Monterosso 94

Phenomena

Human beings’ identification with fictional characters and their beliefs about anti-social behaviors like revenge.

Epistemologies

The complexity of literature cannot be fully captured through scientific reduction.

Assumptions

It’s possible for participants to self-report their beliefs (this study does not involve fMRI scans).

Methods

The describe in great detail they way they crafted the literary texts included in their study and offer full examples of what they used in the study. As with the study published in Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, the results were statistically analyzed.

Works Cited

Alderson-Day, Ben, et al. “Processing Speech and Thoughts during Silent Reading: Direct Reference Effects for Speech by Fictional Characters in Voice-Selective Auditory Cortex and a Theory-of-Mind Network.” Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, vol. 32, no. 9, Sept. 2020, pp. 1637–53. Silverchair, https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_01571.

Fletcher, Angus, and John Monterosso. “The Science of Free-Indirect Discourse: An Alternate Cognitive Effect.” Narrative, vol. 24, no. 1, Jan. 2016, pp. 82–103. [link to article here]

Pupyrev, Sergey, et al. “Edge Routing with Ordered Bundles.” Computational Geometry, vol. 52, Feb. 2016, pp. 18–33. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comgeo.2015.10.005.

Repko, Allen F., et al. Introduction to Interdisciplinary Studies. 1st edition, SAGE Publications, Inc, 2013. [link to chapter here]

Featured Image

“Neurowissenschaftliches Forschungsprojekt” by Ars Electronica Center is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.