Now that I have a good sense of the project I’m working on (I’m still calling it “How We Read”), I can start identifying the various disciplines that I will need to engage to do this work. But first…

What’s Happened Since My Last Post

I’m a few weeks into my project to teach a literature course with no reading list and…

It’s hard.

One of the main reasons is because it requires a style of teaching that is very different from what I’m used to using. I was trained to teach literature through student-produced arguments. Students read texts that I assign, they develop questions about one or more of them, and they read and do research to answer those questions to produce an argument (the answer to their question). When there’s no reading list, thing don’t proceed along this typical path. My students are writing about all sorts of different texts (many I’ve never read myself) and I’m not asking them to craft an argument–just share what they’re learning.

Has My Sense of the Problem Changed?

In my first post, I broke the problem down into three parts

- Time: Yes, students are still busy and struggle to set aside time to really read for class. I’ve been recommending free audio recordings and encouraging them to think of reading the things they’ve chosen as part of their “down time.” I don’t know if that’s proving helpful yet or not.

- Motivation: I definitely see a big difference in student motivation with the shift away from assigned reading. Conversation in class about literary works that students have enjoyed was a great way to introduce the course, and I’m hearing from some students that they were exciting as I described the structure on the first day of class.

- Recommendations: This is still a problem and I’m still thinking of ways to solve it. If I don’t have a reading list, I need some way to help students decide what they will read. I have made a discovery, though, that I think is really important. I’m not just going to be taking in information from students about what they like and spitting out recommendations. There are plenty of recommendation engines out there that do this (not all good, and there are lots of ways to improve on them, as Zoe is exploring), but my goal is to base the recommendations not on the things students enjoy, but their answer to the question “Why did you like this?” This has more to do with the emotional response the work caused in the student, so I need them to feel comfortable sharing that with me and letting me help them figure out how it happened. So far, students are very willing to share things they love and describe their responses, so I’m hopeful this is possible.

These three components of the problem all still exist, but as I attempt to address these, a new problem has emerged.

Problem #4: There’s No Structure in Place for Teaching Literature Without a Reading List

This is not how I was trained to teach literature and I’m making it up as I go. This is fine, I guess, but it leaves me feeling very unmoored. I’m trying to remind myself that I’m trying to find a method that will help others not feel so uncertain (otherwise, what professor will make the shift?).

I said that there’s no structure for this, but that’s not exactly true. I learned from Angus Fletcher that he teaches without a reading list. It was in conversation with him that I first considered teaching without a reading list, and I asked him if he could share his teaching materials so I could see how he does it. He said that he doesn’t write down most of the things he says to his students, but he did share a syllabus and agreed to let me ask questions and try to extract from him the method he uses so I can adapt it for use in my classes (and hopefully describe it for others). We’re meeting every couple of weeks, and have started to think about grant-funding we can pursue to build the recommendation tool I’m imagining. This has been incredibly beneficial. Having a conversation with an actual human being who understands the problem you’re addressing is an incredibly efficient way to get your bearings. This won’t always be available, but when it is (as in, when you are taking a course with a professor!) I encourage you to take advantage of it.

From Projects to Disciplines

So, the task for assignment two is to explore disciplines that will help you pursue the project you have envisioned through assignment one (or a new one if you change your mind!). Before we get into this, I want to encourage you all to check out chapter five of the textbook Introduction to Interdisciplinary Studies by Allen F. Repko, Rick Szostak, and Michelle Phillips Buchberger. This is a book that I considered, but decided not to require in this course. I really like the chapter on disciplines, though, so I’ve made it available for all of you as a pdf. The chapter begins with multiple definitions of “disciplines,” ultimately building toward a single definition: “A discipline is an identifiable but evolving domain of knowledge that its members study using certain tools that serve as a way of knowing that is powerful but constraining” (89). The chapter goes on to explain how different disciplines approach phenomena in the world. I think it will be useful for all of you to refer to this full chapter as you try to determine what disciplines you want to explore for this assignment. I think it does a good job of explaining how different disciplines approach the phenomena they study. By way of example, I want to describe how I’ve been exploring multiple disciplines to pursue my project.

So, What are the Disciplines I’m Using So Far?

English: Narrative Theory

I’ve realized that, for the magical new course I’m creating that will encourage students to actually read, I need a slightly different structure at the beginning of the semester. I went into the semester thinking I was going to be able to make recommendations based on the texts students chose, but that’s not exactly the case. I now realize that I can’t make recommendations until students do some work figuring out what it is about the literary works they’ve chosen that prompted their response. In order for them to do this, I need to show them how. This is something my training in an English Ph.D. program has equipped me to do. I’m drawing on a particular field of analysis within English studies called Narrative Theory. This in an international field of study that is interdisciplinary (in episode 26 of the Project Narrative podcast, for example, Jim Phelan speaks with Lindsay Holmgren, a narrative theorist who works in a department of management). There are many definitions of the field, but I like the definition on The Project Narrative website, which explains that “narrative theorists study what is distinctive about narrative (how it is different from other kinds of discourse, such as lyric poems, arguments, lists, descriptions, statistical analyses, and so on), and how accounts of what happened to particular people in particular circumstances with particular consequences can be at once so common and so powerful.” I think this definition emphasizes that the field studies a phenomenon (narrative) that impacts everyone’s lives, whether they scrutinize it or not.

It’s one thing to do narrative analysis myself. I can do that. But the structure I have in mind for this new and improved literature course is based around empowering students to figure out how to do this analysis for themselves. I don’t want to be in a position of saying “here’s why you like this text…now read this.” I want to help students make these connections on their own. And so this means that I’m not only interested in narrative theory. I’m also interested in pedagogy.

Pedagogy

Pedagogy, it turns out, is also interdisciplinary. Teachers who specialize in many different disciplines study how best to teach and they often use the methodologies of their disciplines when examining the effectiveness of their teaching. A social scientist (like a psychologist or sociologist) is likely to analyze their teaching using methods that involve gathering data (surveying students, for example, or assessing how outcomes from the course are met according to specific artifacts produced by students). I’m interested in these things as well, but I tend to focus first on the ethical dimensions of the power relationship between teacher and student (this could be because I study the humanities). One of the most influential ideas I’ve encountered about pedagogy comes from a writer named Paolo Freire, who developed a critique of what he calls “the banking model of education.” I was in graduate school when I first read Freire’s book The Pedagogy of the Oppressed (this link will take you to the chapter in which he introduces the concept). This model describes a system of education (standard at the time he was writing and still present in many classrooms today) in which students are seen as containers that receive deposits of knowledge from instructors (71). In this structure, professors have knowledge and students need to receive it, but this doesn’t account for the fact that new knowledge is created constantly (and it is far from empowering for students, who are passive in the process). Freire presents instead a problem-posing model of education, which I try to implement in the classroom. “Liberating education, he explains, consists in acts of cognition, not transferrals of information” (79).

Though this particular model from the field of pedagogy has been part of my thinking for many years, it took me time to see how it connects to this project. I’ve now realized, though, that I don’t simply want to create a system in which I make recommendations to students. I want students to be involved in discovering what they like and empowered to find other things like it. We live, after all, in a world of knowledge abundance. Professors do not hold this knowledge locked away in their brains–it is everywhere. The key is to learn how to find it. My hypothesis is that seeing the connections other students have made (something not typically shared) will further encourage students and give them ideas of new texts to try.

So, in addition to helping students identify the features of the texts they already like (by getting better at teaching narrative theory), I also want them to be able to see what actual students are reading and discovering about their reading. The first step in doing this is to gather that data, and I think I’d like to do this by asking students in my courses to complete a simple survey that I can use to build a visualization that grows each semester. What this means is that I’m now combining narrative theory and pedagogy with the social sciences, where survey methodology is taught. My project is getting more and more interdisciplinary.

Social Science: Survey Methodology

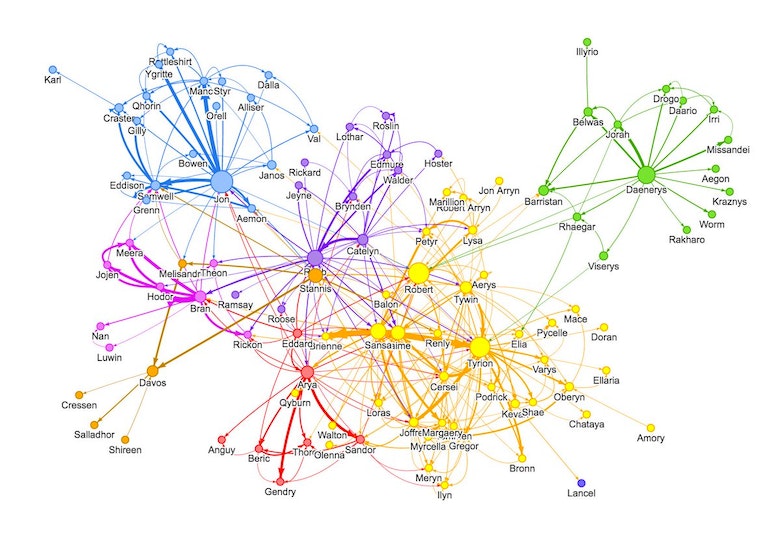

Social science research is new for me. I haven’t incorporated surveys into my research before, so I’m learning how social scientists do their work. I have to make sure I have appropriate approval before studying human subjects. This is called Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval and it’s a complex process to get the paperwork together (and I’ve definitely asked my colleague in sociology to help me as I figure it out!). Even before I write my survey and apply for IRB approval, though, I need to imagine what I want my visualization to contain so I know what questions to ask. I have in mind a network graph that looks a bit like the one below, but with different sorts of data (this one features connections between characters in Game of Thrones).

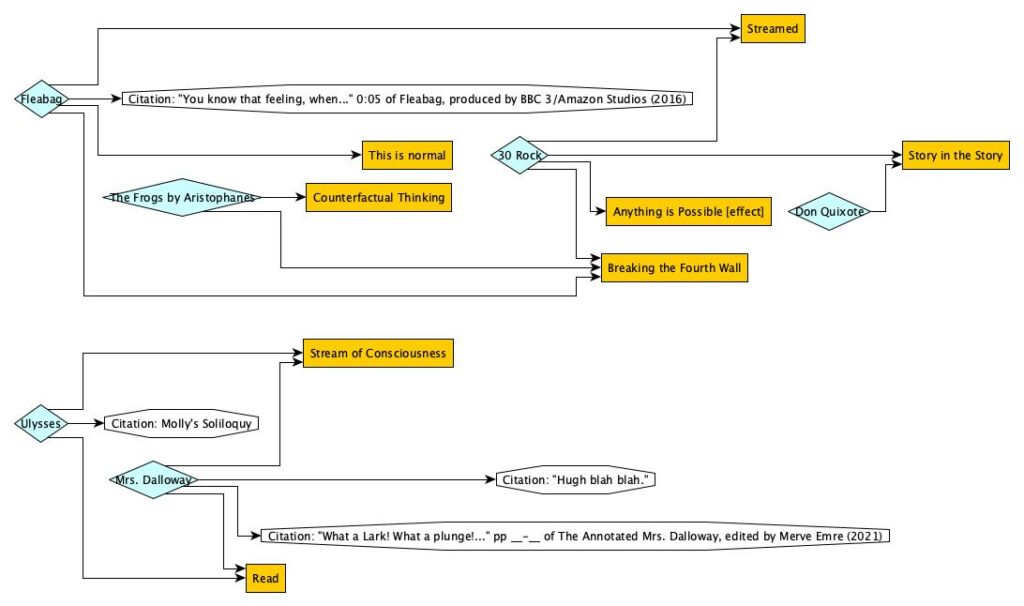

I am envisioning one set of circles (called nodes) representing specific works of literature, another set of circles representing effects reported by readers, and another set of circles representing the literary techniques readers believe have caused those effects. These will be connected to one another with lines (called edges). Over time, this network will visualize many different literary works that have similar effects and use similar techniques, and this will supplement other types of discoveries and recommendations. If students gravitate toward specific effects or specific techniques, the visualization will show them other literary works that do the same thing.

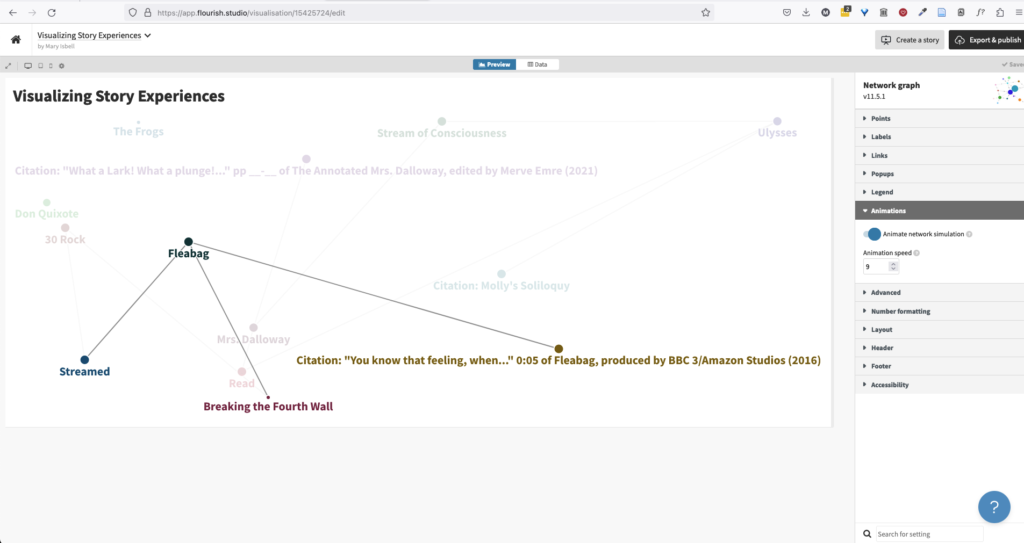

I’ve worked in an interdisciplinary field called digital humanities since I was in graduate school, so I’ve seen this sort of work before. I know that I am entering into the field of data visualization and that the specific visualization I want is a network graph. Unfortunately, knowing the name of the field is a far cry from being able to use the methodology! There are many tools around for building a network graph, but my experimentation led to unsatisfying results. Flourish offers the possibility of a beautiful network graph, but all I got was this:

And then I remembered. Data visualizations exist because mathematicians developed ways of modeling data. So I wrote to a colleague in the math department.

Mathematics

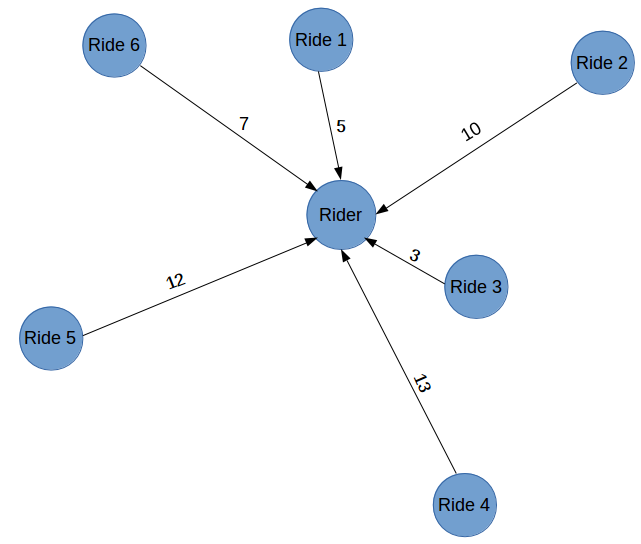

In my first conversation with my colleague in math, Dr. Houssein El Turkey, I described what I was hoping to do and he helped me start to understand what a network graph actually is. It draws on the field of graph theory. I wouldn’t have expected this going in (because I assumed the math would be incomprehensible to me), but I found it VERY useful to read what a graph actually is before returning to the task of actually trying to build one myself. I had to fully understand nodes and edges before I could envision how I want to use them. He suggested that I just draw what I wanted the graph to look like before actually trying to get it built digitally. He also suggested that I send him an e-mail that he could share with his colleagues who work on graph theory because it’s not his specific area of study. The e-mail I sent him took quite awhile to prepare because I was drawing my ideal network graph in Canva.

He sent my message around and then sent me back many suggestions of resources. I need to stress here how crucial it was for me to suppress my desire to pretend I understood more than I did (to “blag,” as we’ve discussed before). I have learned over the years not be afraid to look ridiculous when asking questions of experts. I did my best to explain what I did understand what was still confusing to me. As responses rolled in, I explored a number of tools, including gephi and R, but the most helpful resource was an explanation of graph theory that one professor uses when he teaches the concept to students. Because I didn’t try to hide my ignorance, I got resources that would help me understand better.

The authors of the recommended graph theory lecture open with an example of the usefulness of graphs when determining which Uber driver is sent to pick up a person hailing a ride through the app (Friend). This explanation, along with the list of many other applications for graphs, really helped me wrap my head around what graphs are and the fact that they’re used in many ways other than the way I want to use them. In this process, I realized that the tool I want to use to visualize student reading is actually integral to recommender systems, which also interest me.

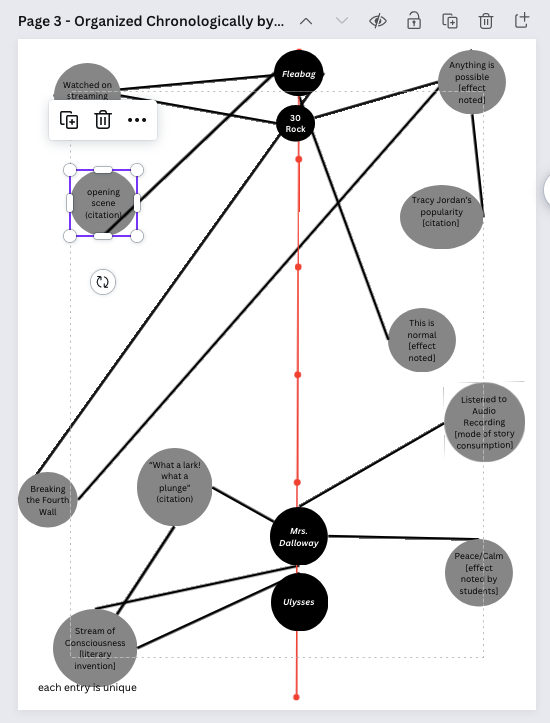

And then, a weird thing happened. I discovered the perfect tool for my purposes because of a completely separate project. I won’t bore you with the details of that one, but I wound up on a zoom call with a Dutch copyright lawyer who has developed a way to visualize the complexities of copyright law for museums and libraries through decision trees. I wanted to hire him for a different project I’m working on, but he told me that I could do the work myself very easily. He does all of his work with a free tool called yEd. I started playing around with it and now I think I’m on the right track. I can import small amounts of test data and then manually manipulate what the graph looks like. This will help me figure out the settings I want to use and refine the data I want to collect through my survey. It’s not beautiful yet, but it’s very functional.

Reflecting on Where I Am Now

When I first started thinking of tackling the issue of students not reading, I didn’t think that I’d be engaging with psychology and mathematics to solve it, but I think this offers an illustration of the value of interdisciplinary thinking. I hope you’ve been able to see in the experiences I’ve shared that I’m reaching out to experts when I’m venturing outside the fields I’m already familiar with. These are the people who are helping me find the right things to read and helping me clarify my thinking when I’m stuck. It’s a jungle out there on the Internet. Rely on humans wherever possible to help you navigate it! A great place to begin is class discussion.

Works Cited

Freire, Paolo. Freire-Pedagogy-of-the-Oppressed. Continuum, 2005. Internet Archive, http://archive.org/details/freire-pedagogy-of-the-oppressed.

Friend, Derek, and Alex Greenwald. “Lecture on Graph Theory.” Graph Theory, 25 Nov. 2019, https://kevintshoemaker.github.io/NRES-746/graph.theory.html.

Phelan, Jim. Podcasts | Project Narrative. 26, https://projectnarrative.osu.edu/podcasts. Accessed 7 Feb. 2024.

“Project Narrative.” The Ohio State University, https://projectnarrative.osu.edu/about/what-is-narrative-theory. Accessed 6 Feb. 2024.

Repko, Allen F., et al. Introduction to Interdisciplinary Studies. 1st edition, SAGE Publications, Inc, 2013.

Featured Image

“How to Build a Knowledge Graph” by Stardog. All Rights Reserved.