After months and months of pestering me, I guess my dad has finally won, and I do have to reluctantly admit I enjoyed reading this book. I hadn’t read a satirical book before, and I was reluctant to try one. I thought it would make me feel bad about myself, and it would end with me being upset with my own actions. So far, The Screwtape Letters hasn’t caused this, and I find myself laughing more often than I expected. Teaching moral lessons by having demons express the inverse is so entertaining, at least to me. The narration and plot go hand in hand to sculpt the perfect satirical story filled with irony.

What I’m Experiencing

To go perfectly with a plot full of irony, I’ve been experiencing a lot of self-irony. I’m not a perfect person by any means, and seeing things I’ve so clearly done before makes me laugh. The entire plot is built around irony, and a lot of the emotions it evokes revolve around my own sense of self. I think a big part of this is the use of the narrative technology of the God Voice. Screwtape is a “pure being” and doesn’t feel like we humans do, and it feels almost like you can’t connect with him. Instead, it feels more like you’re listening to him and reflecting on what he’s saying more as a person yourself than linking it to a character. When Screwtape brings up specific actions that we simply as people tend to have, you can’t help but look at your own behavior and see you’re behavior is no better than his “patient.” At the same time, when you acknowledge that, you can laugh at it or look at it and accept that you aren’t perfect. I marked parts of the chapters as I went that made me feel these self-emotions strongly.

Excerpts, Technologies, and Experiences

Even if a particular train of thought can be twisted so as to end in our favour, you will find that you have been strengthening in your patient the fatal habit of attending to universal issues and withdrawing his attention from the stream of immediate sense experiences. Your business is to fix his attention on the stream. Teach him to call it “real life” and don’t let him ask what he means by “real”.

…

Once he was in the street the battle was won. I showed him a newsboy shouting the midday paper, and a No. 73 bus going past, and before he reached the bottom of the steps I had got into him an unalterable conviction that, whatever odd ideas might come into a man’s head when he was shut up alone with his books, a healthy dose of “real life” (by which he meant the bus and the newsboy) was enough to show him that all “that sort of thing” just couldn’t be true.

Letter 1 of The Screwtape Letters (transcribed from chapter)

This excerpt is from the very first chapter, which sets up the entire voice of Screwtape. The Prologue reminds us that we shouldn’t take everything he says as truth as “all devils are liars.” However, we do get this tone of voice that is almost talking down to his nephew Wormwood, which makes sense since he’s a senior devil versus Wormwood’s junior tempter. Throughout the whole letter series, Screwtape uses a God Voice, or in this case, a Devil’s Voice, since it’s showing that God voice from the devil’s perspective. He knows the human experience and how to twist it to the devil’s advantage. The plot uses irony constantly, with Screwtape telling Wormwood about all of these “patients” he’s had and how he’s tempted them away from God. In this letter, Screwtape is telling Wormwood about the power of redirecting attention. The irony comes from us knowing that Screwtape has tempted patients away from God and Heaven through these methods, while the human “patients” didn’t know until afterward.

Now, with this one specifically, I felt a lot of self-irony, especially when Screwtape showed what he meant with his patient. I had been having a minor moral dilemma; it was over housing for next year and if I would be a bad person for prioritizing my needs and not living with someone next year. It was nothing earth-shattering or coming to a religious epiphany, but still, it was a moral dilemma for me. In the middle of this, I got an email mthat y prescription was ready for pickup, so I got myself together and went to Walgreens to pick it up. Just the simple act of leaving the house and picking up that prescription, an act that took maybe 20 minutes at most because there was just a long line, had that moral dilemma out of my mind. When I reread the passage, I actually laughed because, wow, I just did that same exact thing. I got distracted from my thoughts by “real life,” and I wasn’t worried anymore about being a bad person.

When he goes inside, he sees the local grocer with rather an oily expression on his face bustling up to offer him one shiny little book containing a liturgy which neither of them understands, and one shabby little book containing corrupt texts of a number of religious lyrics, mostly bad, and in very small print. When he gets to his pew and looks round him he sees just that selection of his neighbours whom he has hitherto avoided. You want to lean pretty heavily on those neighbours. Make his mind flit to and fro between an expression like “the body of Christ” and the actual faces in

the next pew. It matters very little, of course, what kind of people that next pew really contains. You may know one of them to be a great warrior on the Enemy’s side. No matter. Your patient, thanks to Our Father below, is a fool. Provided that any of those neighbours sing out of tune, or have boots that squeak, or double chins, or odd clothes, the patient will quite easily believe that their religion must therefore be somehow ridiculous.Letter 2 of The Screwtape Letters (transcribed from chapter)

The plot is again using irony in combination with the narrator’s God voice. The irony comes from knowing that we, as humans, tend to judge people before knowing them. Having it be explained here that this is caused by devils trying to tempt us to do bad is revealing how that occurs within this story. It pushes you as a reader to notice if you’re judging people without really knowing them. Now, we don’t have the patient’s worldview in the story, and we don’t know if it works and he begins to think these things. We can only assume he is since Screwtape seems to be pleased with Wormwood’s progress in future letters to him.

This made me feel that self-irony again, but just not as strongly as the first time. I know I have judged people before really knowing them, and I know people have judged me before getting to know me. I know when I do that I usually end up feeling bad, so I tend to try to check that habit. I think that’s why the self-irony wasn’t as strong as the first one; I have already acknowledged that this bad behavior can occur and am trying to prevent it.

This is also the chapter where Screwtape got a voice in my head and became more distinct to me. He had a more British voice (probably due to the location of the story); he spoke softly and pointedly. I imagined it to be like the little devil on the shoulder whispering in a person’s ear, which might be where the soft voice came from. I think the pointedness also comes from the fact that he does have so much authority in the letters and would probably speak with it.

The mere word phase will very likely do the trick. I assume that the creature has been through several of them before — they all have — and that he always feels superior and patronising to the ones he has emerged from, not because he has really criticised them but simply because they are in the past.

…

Nice shadowy expressions — “It was a phase” — “I’ve been through all that” — and don’t forget the blessed word “Adolescent”,

Letter 9 of The Screwtape Letters (transcribed from chapter)

The same use of the plot technology of irony is being used here and evokes in me self-irony. Ok, so admittedly, I’ve been through a lot of phases, especially in high school. I went through the emo phase (which frequently comes back with a vengeance), I went through a goth phase (very closely related to that emo phase), and I went through a flannel phase. I feel like that adolescent age is where you try so many things to try to find yourself, but I also acknowledge how indignant I can be when those phases from high school are brought up. I absolutely hate when they’re brought up, especially the ones that passed completely- specifically the goth and flannel ones. So, reading this passage, I absolutely started cackling. It so perfectly reflected actions I’ve done, getting so offended by the mere mention of my high school phases.

As you ought to have known, the asphyxiating cloud which prevented your attacking the patient on his walk back from the old mill, is a well-known phenomenon. It is the Enemy’s most barbarous weapon, and generally appears when He is directly present to the patient under certain modes not yet fully classified.

…

On your own showing you first of all allowed the patient to read a book he really enjoyed, because he enjoyed it and not in order to make clever remarks about it to his new friends. In the second place, you allowed him to walk down to the old mill and have tea there — a walk through country he really likes, and taken alone. In other words you allowed him two real positive. Pleasures.

Letter 13 of The Screwtape Letters (transcribed from chapter)

Ok, so here we have Screwtape explaining how Wormwood messed up by allowing his human some actual happiness. It’s essentially saying that the happiness granted from true acts of joy makes it impossible to lower someone. The narration relies very heavily on Screwtape’s God Voice, and the plot itself is ironic. The human obviously doesn’t know that he is now safe for the time because he had genuine joy in pleasures, but we, as the readers, now know. It also nudges you towards that too, taking time for yourself to enjoy the things that make you truly happy.

I felt a lot of self-love at this part. It felt like just a moment where I could go, yeah that makes me happy, like well and truly happy. Upon further reflection, I realized that when I have done something for myself that makes me actually happy, it is hard to drag me down. Having it visualized as this cloud that prevents the negatives actually made me giggle. A little bit about myself: I struggle really hard to do anything for myself. If I have to choose between making someone else happy or myself, I’ll usually choose someone else. So it felt really powerful to me to have this section on taking time to enjoy life’s pleasures and what makes you happy. It made me feel love towards myself and realize I do need to take more time for the things I actually do enjoy, and that might increase that feeling of self-love.

He wants each man, in the long run, to be able to recognise all creatures (even himself) as glorious and excellent things. He wants to kill their animal self-love as soon as possible; but it is His long-term policy, I fear, to restore to them a new kind of self-love — a charity and gratitude for all selves, including their own; when they have really learned to love their neighbours as themselves, they will be allowed to love themselves as their neighbours. For we must never forget what is the most repellent and inexplicable trait in our Enemy; He really loves the hairless bipeds He has created and always gives back to them with His right hand what He has taken away with His left.

Letter 14 of The Screwtape Letters (transcribed from chapter)

So here, Screwtape is talking about God and his folly in loving mankind. He’s again using a God Voice to state what he objectively knows beyond not only Wormwood, but it even feels like he’s saying this to the reader of the story. Here, it feels more like the plot is using a parable and less irony. Obviously it’s a satirical book, so the irony is still present in the fact that we as readers know that God is trying to aid mankind while the humans in the story may not. But here, it feels more like a parable told from the other moral side, where it teaches the religious lesson of God’s love. That parable is powerful, making me even experience self-love.

I’m far from religious; it just feels like a lot of men talking about a greater power, and sometimes it feels like they use their “connection” to God as a way to push their own agenda and be seen as infallible. But here, it felt like this was a genuine expression of how the author feels God’s love works. It made me tear up, and I didn’t expect it. I try really hard to be a good person, to support everyone I can, and like I said, I do prioritize others over myself at points. I’ve been grappling with this whole am I a good person or not thing because how can I be a good person if I do all these things but I’m not always kind to myself? This little passage, though, made me love the part of me that always tries to do the right thing, but also love that part of me that is selfish and wants things for myself even if it’s usually not acted on, and the anxious part that is always so nervous over hurting anyone’s feelings. It made me love myself not for being a “good person” but for being me. Nobody is perfect, but my flaws make me human, and people do love me well and truly.

Even in the nursery a child can be taught to mean by “my Teddy-bear” not the old imagined recipient of affection to whom it stands in a special relation (for that is what the Enemy will teach them to mean if we are not careful) but “the bear I can pull to pieces if I like”.

Letter 21 of The Screwtape Letters (transcribed from chapter)

So, in this letter, Screwtape is teaching about possessiveness and how Wormwood can shift the human’s thoughts to revolve around what he perceives as his. I don’t quite know how to describe the technique, but it most closely resembles irony. The thing being revealed isn’t really to a character unless you want to think of Wormwood as the one to get the revelation of human nature. It feels like it was meant more to make the reader look at their nature and take notice of how we always revolve around what is “ours” and not really care as long as we possess it.

Now, with my own emotions, I relate way more closely with the first example of Screwtape’s explanation of possessiveness in young children despite not being that age anymore. I was never a destructive child; the most destruction I did was caused by loving my stuff too much. I was born in an emergency C-section and, more importantly, wasn’t breathing. I got put in the NICU, which really freaked my parents out, and there were dozens of wires attached to me. My mom couldn’t go see me, so my dad did, and it made him really sad to see in his own words “his baby girl all alone in that tank.” He made an impulse decision and bought two little rattle stuffed animals- Eeyore and Tigger from Winnie the Pooh. He would say to my mom later that they matched the nursery back home, which was Winnie the Pooh themed. I wouldn’t know, but he firmly defends it that way in any retelling of the story. But those two stuffed animals, I still have after 21 years, and I still sleep with them every single night when I’m home. This passage really made me feel self-acceptance. I thought I was like weird for doing this, still sleeping with them even when I’m fully grown and almost done with college. But reading this, it clicked to me why I still need them to sleep, they’re an object of my affection with a special relationship to me. It’s not weird for me to love these things that in themselves were an act of love for me.

The horror of the Same Old Thing is one of the most valuable passions we have produced in the human heart

…

To experience much of it, therefore, they must experience many different things; in other words, they must experience change. And since they need change, the Enemy (being a hedonist at heart) has made change pleasurable to them, just as He has made eating Pleasurable. But since He does not wish them to make change, any more than eating, an end in itself, He has balanced the love of change in them by a love of permanence.

Letter 25 of The Screwtape Letters (transcribed from chapter)

In this letter, Screwtape is talking about the horror that comes with the human experience he coined as the “Same Old Thing.” It’s that fear of nothing changing and the desire for change. Now, it is ironic in the plot, as Wormwood himself wants the patient to not change either, to stay firmly under his control, and to continue to ride that high. So this did make me feel self-irony; I have a love-hate relationship with change. Sometimes, I love the freedom of change, getting to experience new things that may be exciting or may just blow up in my face. But at the same time, there are things I never want to change, like relationships I have with people that I never want to lose. Having Screwtape pointing out this contradiction I know at least I struggle with was kind of funny to me. It is a funny balance of how even just as a person, I both love change and love permanence. For example, I know that every day, the sun will rise and set, and the moon will too. I know that every day before I go to bed, I will take a shower, and then text my parents, “good night I love you.” I love the comfort of knowing something is going to happen, but also as the same time, there are things even if I do set a schedule for myself, I feel overwhelmed when they never change. One thing I can think of is something like a Snap Streak; no matter how many friends try to get me to start one, I will never follow through. It’s overwhelming to me and anxiety-inducing to have something I have to do every single day. This is a contradiction to that permanent thing I specifically do of texting my parents to go to sleep. So, having Screwtape point out that kind of contradiction made me laugh because I acknowledge I do that. It’s funny how contradictory it is, and the self-irony I felt was really strong, but it wasn’t bad to be able to laugh at myself.

But in the intellectual climate which we have at last succeeded in producing throughout Western Europe, you needn’t bother about that. Only the learned read old books and we have now so dealt with the learned that they are of all men the least likely to acquire wisdom by doing so. We have done this by inculcating The Historical Point of View. The Historical Point of View, put briefly, means that when a learned man is presented with any statement in an ancient author, the one question he never asks is whether it is true. He asks who influenced the ancient writer, and how far the statement is consistent with what he said in other books, and what phase in the writer’s development, or in the general history of thought, it illustrates, and how it affected later writers, and how often it has been misunderstood (specially by the learned man’s own colleagues) and what the general course of criticism on it has been for the last ten years, and what is the “present state of the question”. To regard the ancient writer as a possible source of knowledge — to anticipate that what he said could possibly modify your thoughts or your behaviour — this would be rejected as unutterably simple-minded.

Letter 27 of The Screwtape Letters (transcribed from chapter)

So this is towards the end of the book, where World War I is occurring, and Screwtape is stating that humans tend to when they read about a historical point of view they tend to fixate on the why they said what they did and not what they actually said. So this is ironic within the plot because Wormwood is at this point listening to Screwtape less and less, and therefore messing up more and more. Screwtape, in this case, is functioning similar to those ancient writers for humans, where Wormwood is reading the letters but not really seeing he is falling into the same mistakes the humans do with “The Historical Point of View.” Here, I again felt that self-irony. This whole book is written in a different time period, from my own, and while the preface states not to trust anything Screwtape says as he is a devil, I realized I never stopped to actually question if any of it was true. The very thing that was being criticized I was just doing because I never stopped to think about whether what I was reading was true. It came from the most unreliable narrator in the story, but I’ve accepted everything as truth. I couldn’t help but laugh at that; I truly just never thought about it until that point. I was the exact thing they were satirizing, and it made me laugh so hard.

Wrap-Up Thoughts

Overall, I think the plot in this story is full of irony, but it’s also a parable. C.S. Lewis was very heavily influenced by Christian religion and, specifically, theological issues within it. As I said, going through the book evoked a lot of self-emotions. I never felt connected to the characters due to that use of the God Voice in narration. Screwtape simply felt so different that I couldn’t identify with him, and so instead, a lot of the emotions came back at me and made me reflect on myself rather than writing it off as a character.

Outside of the book, though, it made me feel connection. My dad is very religious, so he’s read it before, but he decided to read it again alongside me. My friend Ben, who is quite literally the most religious person I know, had read it and also decided to reread at least part of it with me. Sitting in chapter just talking about it, Charlie, who is not religious at all, thought it was interesting and wanted to read it when I was done. It really felt like this book served as a medium to bond with others and form that feeling of connection.

Works Cited

Lewis, Clive Staples. The Screwtape Letters. Geoffrey Bles, 1942.

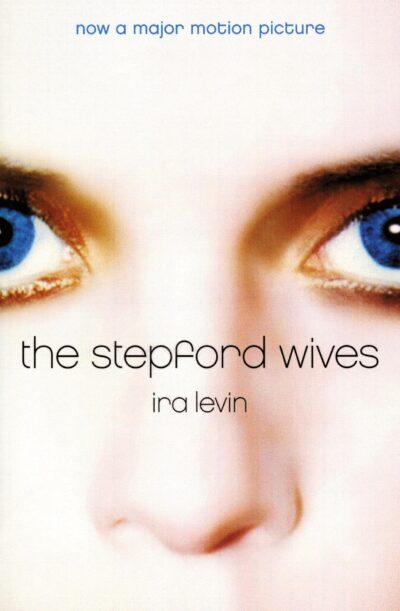

Featured Image

Nova, Max. “Review – the Screwtape Letters.” Book Reviews, 13 May 2019, books.max-nova.com/screwtape-letters/. Accessed 26 Mar. 2025.