How social media has shaped masculinity

Over the past 20 years, social media has become a global phenomenon, one deeply ingrained in modern life with platforms such as TikTok, Instagram, and Facebook having a combined total of 3.5 billion active users. These platforms are instrumental in forming and sustaining friendships, facilitating advertising and networking, and raising public awareness. The algorithms on these apps promote content to users based on engagement; posts or videos with more likes, comments, or shares are more likely to be shown to users. However, the content of these posts and what they promote, though popular, can vary greatly, and some of it, as well as the connections it helps form, can be dangerous. Since the conception of the internet, and increasingly so since the advent of social media, online spaces have become hotbeds for harmful ideologies, particularly those that target youth, and it is those that target young men which have become of particular concern.

This reality was starkly reflected in the Netflix show Adolescence, which took the internet by storm in March of 2025. This series brought the issue of toxic masculinity, a socially destructive conception of masculinity more thoroughly defined later, into the media mainstream and blatantly displayed how it can affect young men, as well as its potentially fatal consequences. Adolescence’s bleak, albeit accurate representation of gendered aggression and social media’s role in it deeply resonated with its wide audience. Unfortunately, Adolescence and the message it sends isn’t as fictional as one might hope. In the United Kingdom alone, where the show is set, one woman is killed every three days by a man. In the United States, 22.7% of homicides are committed by men against women, making this the second-largest gender-based homicide demographic. These are just a handful of demonstrations of the extreme outcomes of a pervasive and topical issue in today’s media centric world.

While these statistics are a striking display of the possible outcomes of unchecked misogyny, they do not help to understand how or why such violence may occur. Many online social spaces and the beliefs they promote are intricately tied to the causes of these crimes. Internet communities such as the “manosphere,” an online phenomenon targeting men, encourage ideas such as misogyny, violence as a means to power, and dominance as hallmarks of a “man.” This online echo chamber of violent and misogynistic beliefs is what many young men are finding themselves immersed in today. This article will explore how social media is contributing to a concerning increase in toxic masculinity as well as dangerous gendered ideals among young men which is damaging to their mental health. It will discuss social media’s contribution in the spread of these toxic beliefs, beginning with the evolution of toxic masculinity before delving into its effects on young men and concluding with potential solutions for this insidious and proliferating issue.

What is “toxic masculinity”?

Toxic masculinity, as referred to earlier, is an umbrella term that has been used to refer to the forms of masculinity that are socially harmful. Often it is used when issues such as misogyny and masculine violence are involved, which themselves are tied to hegemonic masculinity, a form of masculinity that values and promotes the social dominance of men through violence, aggression, and the subordination of women and other minority groups. These sociocultural practices are common and are encouraged in the “manosphere,” which the United Nations defines as a catchall phrase for the “online communities that…[promote] narrow and aggressive definitions of what it means to be a man – and the false narrative that feminism and gender equality have come at the cost of men’s rights”. Communities such as these exist on and because of the internet, with its ability to connect people with common beliefs and interests. With the rise of social media, these communities have only increased in size, number, and toxicity. However, in many cases, men may happen across these communities without knowing what they are. They may appear to be centered around self-improvement, carefully drawing people in while promoting unhealthy behavior under the guise of self-help.

Men Going Their Own Way (MGTOW) is one such example of these communities. As innocuous as the name may sound, it belies the misogynistic, violent, and male-supremacist nature of this group. The members of this community, follow a severely anti-feminist precept, the tenets of which include statements such as “…modern “Western” society has been corrupted by feminism…” and that “…feminism ensures that men are either actively subjected to (or at serious risk of) discrimination”. These are indubitably extreme beliefs, and one may wonder how exactly anyone could adopt these; however the answer is much simpler than it seems, “Individuals may adopt the MGTOW ideology for any number of reasons, but several common precursors include being rejected by women, being subjected to perceived discrimination or unrealistic male beauty standards and shifting cultural norms”. With nearly 33,000 members and counting, MGTOW is the epitome of the online toxic masculinity epidemic and displays exactly how men can become involved in these communities.

The “real man” ideal

While it may be clear how toxic masculinity is harmful for the sociologically defined minority groups which it targets, it may not be as clear how toxic masculinity hurts the men involved in it themselves. An article published by the Journal of Clinical Psychology details how hegemonic masculinity shapes men’s self-image and through that their behaviors and conceptions of “manliness”:

“…hegemonic masculinity…includes a high degree of ruthless competition, an inability to express emotions other than anger, an unwillingness to admit weakness or dependency, devaluation of women and all feminine attributes in men, homophobia, and so forth…Hegemonic masculinity is conceptual and stereotypic in the sense that most men…tend to worry lest others will view them as unmanly for their deviations from the hegemonic ideal of the real man”.

Essentially, by adopting a hegemonic viewpoint of masculinity, men both isolate themselves and surround themselves with these ideals. They equate their own value as a man to their alignment with these standards, and they devalue anyone, themselves included, who does not meet them. This includes, as stated, women as a whole and men whom they deem “unmanly”. It is these values that online spaces are espousing and that men, young men especially, are finding themselves involved in. Given that men may stumble upon these communities when trying to find ways to improve themselves, they may be more receptive to these beliefs, on the assumption that if they adopt these behaviors, they will be “better men”, a belief which is then supported by the communities themselves.

This can often have the opposite effect as both social media in general and these communities in particular have been shown to be hazardous for mental health. Social media use, compounded with messages encouraging toxic masculine standards has been associated with increased risk of depression among men. This proves to be an even greater issue when considering the fact that hegemonic masculinity admonishes “emotions other than anger”, including vulnerability, as well as “weakness” and “dependency”. Given this, it is likely that men will be even less motivated to address serious mental health issues at risk of appearing a “weak man”. This illustrates how social media, and hegemonic communities exacerbate the problems associated with toxic masculinity by creating an environment in which men internalize the idea of “vulnerability as weakness”; they jeopardize their mental health for the sake of being perceived as a “real man”.

A toxic pipeline

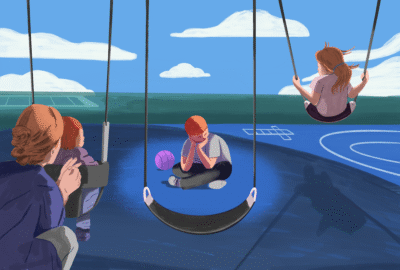

Studies have shown that this is the exact rabbit hole young men fall into, a pipeline that begins with seeking guidance and assistance and ends in toxic online spaces that exploit this vulnerability and abuse it. Boys and young men may enter these spaces unaware of the ideologies they uphold, and are, as one such report details, “algorithmically offered hateful or misogynistic content, which in turn is being normalised by the high levels of their usage…[Content]…initially focused on loneliness and a search for belonging…then pushed topics such [as] hyper or hegemonic masculinity”.

The boys and young men who become entrapped in these cultures are often the victims of a social system that has failed them on multiple counts; from the social media algorithms that lead them into these spaces to the people involved in these spaces who take advantage of the anonymity the internet provides to project these harmful norms of masculinity upon the youth. These boys, who may be alone and isolated and turn to social media as a form of connection, are then met with the facade of it. They gain access to these communities only if they conform to the expectations within them. They adjust their worldviews and self-schemas just to be accepted and by doing so, become both the victims and the perpetrators of toxic masculinity. By only gaining acceptance when they take on the role of a “real man,” they come to believe that they will only be accepted so long as they are “real men” and meet the expectations of one as prescribed by hegemonic masculinity. As young men engage more regularly with toxic masculinity online, their conceptions of gender roles become shaped by the media they consume. They come to view emotional vulnerability as weakness and report negative attitudes towards women. This failure of these young men leads them to believe that acceptance is conditional, that in order to obtain it they must assert dominance and maintain emotional stoicism. By exposing them to these ideals when they are vulnerable, they come to internalize them, regardless of the harm these ideals bring to themselves and others.

Why current solutions have not been successful

The issue of toxic masculinity is much more multifaceted than it seems, far more than has been presented so far. Indeed, some programs intending to resolve this issue can in fact perpetuate the problem. An article by the American Journal of Public Health states, “Some types of public…messaging can reify [the] harmful aspects of hegemonic masculinity that [these] programs are working to change.” This demonstrates how even, and especially, well-intentioned programs can inadvertently reinforce the very issues they aim to resolve, which helps explain why so many campaigns and programs addressing toxic masculinity have failed.

By criticizing toxic behaviors without contemplating the underlying sociocultural circumstances that may lead to them, these programs risk normalizing the issues they aim to solve. Simultaneously, these programs may also demonize the behaviors and the men and boys involved in them, thereby giving those men and boys the opportunity to resist change and to view such programs as personal affronts and attacks. If one views toxic masculinity as both the cause and the effect, they fail to see the reason behind the occurrence of toxic masculinity, and the rise in it, altogether. Therefore, any potential solution to address toxic masculinity must also address the root causes behind it; it must not treat toxic masculinity as the enemy, but as a culmination of a number of factors which has resulted in much harm for those involved in it as well as those impacted by it.

So what should be done?

In order to effectively combat the issues contributing to toxic masculinity online, efforts must both address its current effects and mitigate future ones. Solutions must be mindful of how masculinity is viewed in today’s society, as well as the biases against it, and those who propose these solutions must be cognizant of how the dominant view of masculinity is not the only one. Policymakers, program leaders, and organizers must be aware of and understand how masculine norms and ideals are upheld in society and how intrinsically they are tied to ideas of “what it is to be a man.” Efforts must also be made to acknowledge the intersections between masculinity, race, and socioeconomic status, and how systems of power work to uphold these in vastly distinct and unequal ways. While this article does not explore these intersections, they are still significant underpinnings of many socially defined concepts of masculinity, dominance, and superiority.

Ultimately, the question must not be one of condemnation but of understanding when it comes to the men and boys involved in the cycle of toxic masculinity. The social media platforms that have not only allowed for, but encouraged, the growth of toxic communities though must be held accountable. Restrictions and moderation specifically regarding these issues should be put in place to limit the growth of toxic online spaces. Clearer community guidelines and stricter enforcement of them on social media could be beneficial in curbing the spread of such beliefs through such measures as banning creators who promote harmful, violent, and misogynistic content.

Toxic masculinity and its effects on young men, particularly through its reach on social media is not an easy topic to discuss or solve, but efforts continue to be made. More research focused on this subject continues to be carried out, and with more research, hopefully there comes more effective and compassionate solutions and programs that can break this toxic cycle.

Citations:

Ashar, L. C. (2024). Social media impact: How social media sites affect society. https://www.apu.apus.edu/area-of-study/business-and-management/resources/how-social-media-sites-affect-society/

Bates, L. (2020). Men going their own way: the rise of a toxic male separatist movement. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2020/aug/26/men-going-their-own-way-the-toxic-male-separatist-movement-that-is-now-mainstream

Clemens, C. (2017). What we mean when we say “toxic masculinity.” SPLC Learning for Justice.https://www.learningforjustice.org/magazine/what-we-mean-when-we-say-toxic-masculinity

Fisher, K., Rice, S., & Seidler, Z. (2025). Young men’s health in a digital world. Movember Institute of Men’s Health.https://cdn.sanity.io/files/d6x1mtv1/mo-com-production/e1054b901ac235e16f177a2bca8ee760fb8e6a19.pdf

Fleming, P. J., Lee, J. G. L., & Dworkin, S. L. (2014). “Real Men Don’t”: Constructions of masculinity and inadvertent harm in public health interventions. American Journal of Public Health, 104(6), 1029–1035. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4062033/#:~:text=Abstract,the%20Man%20Up%20Monday%20campaign

Fox, J. A., & Zawitz, M. W. (2010). Homicide trends in the United States. Bureau of Justice Statistics.https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/htius.pdf

Kupers, T. A. (2005). Toxic masculinity as a barrier to mental health treatment in prison. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(6), 713–724. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/8001761_Toxic_Masculinity_as_a_Barrier_to_Mental_Health_Treatment_in_Prison

Men going their own way (MGTOW): What you need to know. (2024). ADL. https://www.adl.org/resources/article/men-going-their-own-way-mgtow-what-you-need-know

Men still killing one woman every three days in UK – It is time for “Deeds not Words.” (2020). Femicide Census. https://www.femicidecensus.org/men-still-killing-one-woman-every-three-days-in-uk-we-need-deeds-not-words/

Metzler, H., & Garcia, D. (2023). Social drivers and algorithmic mechanisms on digital media. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 19(5). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11373151/

Parent, M. C., Gobble, T. D., & Rochlen, A. (2018). Social media behavior, toxic masculinity, and depression. Psychology of Men and Masculinities, 20(3), 277–287. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10798810/

Regehr, K., Shaughnessy, C., Zhao, M., & Shaughnessy, N. (2024). Safer Scrolling: How algorithms popularise and gamify online hate and misogyny for young people. University of Kent. https://www.ascl.org.uk/ASCL/media/ASCL/Help%20and%20advice/Inclusion/Safer-scrolling.pdf

Salter, M. (2019). The problem with a fight against toxic masculinity. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2019/02/toxic-masculinity-history/583411/

Stoeckle, J. (n.d.). Hegemonic masculinity. Office of Teaching & Learning Inclusive Teaching Practices.https://operations.du.edu/inclusive-teaching/content/hegemonic-masculinity

The Evolution of Social Media: How Did It Begin, and Where Could It Go Next? (2020). Maryville University. https://online.maryville.edu/blog/evolution-social-media/

What is the manosphere and why should we care? (2025). UN Women. https://www.unwomen.org/en/articles/explainer/what-is-the-manosphere-and-why-should-we-care